The overthrow of Portugal’s Prime Minister, Marcello Caetano, on 25 April 1974 hailed a watershed moment for the former Portuguese colonies of Mozambique, Guinea Bissau, Cape Verde, São Tomé and Principe and Angola. The Armed Forces Movement (AFM) had overthrown the dictatorship in a mostly bloodless coup, thereby ending Portuguese colonial rule in Africa.

Thus, Angola attained official independence on 11 November 1975 and, while the stage was set for transition, a combination of ethnic tensions and international pressures rendered Angola’s hard-won victory problematic. As with many post-colonial states, Angola was left with both economic and social difficulties which translated into a power struggle between the three predominant liberation movements. The People’s Movement for the Liberation of Angola (MPLA), formed in December of 1956 as an offshoot of the Angolan Communist Party, had as its support base the Ambundu people and was largely supported by other African countries, Cuba and the Soviet Union.

The National Liberation Front of Angola (FNLA), founded in 1962, was rooted among the Bakongo people and strongly supported the restoration and defence of the Kongo empire, eventually developing into a nationalist movement supported by the government of Zaire and (initially) the People’s Republic of China.

The Ovimbundu people formed the base of the National Union for the Total Independence of Angola (UNITA), which was established in 1966 and founded by a prominent former leader of the FNLA, Jonas Savimbi. After its hard-won independence, however, Angola faced a further potential catastrophe as the power-sharing agreement between the three rebel groups collapsed in 1975.

Origins of the Conflict

Ethnic Tensions

A salient reason for the continuation of civil war after independence was a result of the reluctance of the dominant liberation movements to share power within a multi-ethnic society. Unlike former Portuguese colonies, the Angolan people fought their colonisers on three fronts. The MPLA called for a single united front of all anti-colonial Angolan forces, however its popular appeal was largely limited to the Mbundu – Angola’s second largest ethnic group – and the multiracial Mestiqos. The MPLA’s nationalist drive did not appeal to the Bakongo people, who rallied to militant right-wing FNLA leader, Holden Roberto’s, call for the reestablishment of the ancient Kingdom of Kongo in the north of Angola. FNLA supporters were largely rural and remained separated from colonial society, but suffered extensively from land dispossession under colonial authorities in the 1950s. The formation of UNITA in 1966 attracted the largest support base; the Ovimbundu ethnic group, although geographically fragmented, were largely integrated into colonial society, and used UNITA as a vehicle for opposing the ethnic groups supporting the FNLA and the MPLA.

Thus, while a power-sharing arrangement was agreed upon after independence was secured, power struggles ensued almost immediately as the agreement collapsed. This was aggravated by the withdrawal of the Portuguese in 1975; refusing to impose peace or supervise elections, and failing to hand over power to any one party, the Portuguese armies exited Angola and left the country and its future to its own devices. It was here that the common anti-colonial goal was abandoned, and the three dominant liberation movements began a steady struggle for power. On August 1, 1975, UNITA formally declared war on the MPLA.

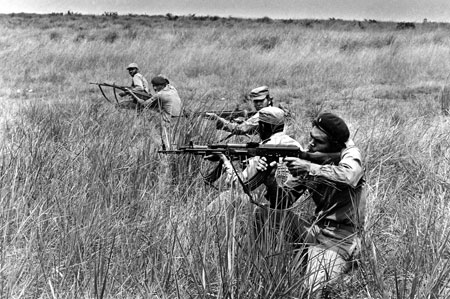

Cuban and Angolan soldiers - Source: www.cubadebate.cu

Cuban and Angolan soldiers - Source: www.cubadebate.cu

500 Years of Colonialism

Much of the ethnic tension between the three warring factions was rooted in differing positions within colonial society prior to independence. Colonial rule resulted in the politicisation of ethnicity by combining and placing vastly differing ethnicities under one centrally administered colonial territory. Additionally, colonialism aggravated ethnic cleavages by introducing and imposing racial and class divisions. As mentioned, the FNLA and UNITA support base was largely drawn from rural communities who had been severely affected by colonial land dispossession. In fact, a frequent criticism of the MPLA by its two opposing movements was that its leadership was widely made up of Portuguese descendents and came from privileged socio-economic standings. This was not entirely incorrect, as MPLA leaders were often from urban areas and used class as an enduring element in their attempt to garner support from the emerging urban proletariat and intelligentsia.

Ideologically speaking, the three movements were also at odds. While the MPLA initially espoused a Marxist-Leninist discourse and later switched to a social democratic model, the rural FNLA and UNITA were far more militant and right-wing, harbouring a distaste for the bourgeoisie MPLA supporters.

Weapons training for Cuban and MPLA soldiers - Source: s3.amazonaws.com

Weapons training for Cuban and MPLA soldiers - Source: s3.amazonaws.com

The Resource Curse

Angola spans around 481,226 square miles along the southwest coast of Africa, and is notably rich in mineral reserves, including oil, iron, copper, bauxite, diamonds and uranium. Angola’s resource wealth became a means of funding the ongoing war between the MPLA and UNITA, with both parties extensively exploiting the country’s oil and diamond reserves. During the years of civil war, UNITA was able to capture several major diamond mines (by capturing the areas of Lunda Sul and Lunda Norte Provinces) which served as a primary resource for financing arms and fuel, and funding the liberation movement’s guerrilla campaigns against the MPLA.

With the approaching independence in 1975, each of the three major contenders began to secure Cold War patrons. The MPLA solicited the support of the Cubans who harboured a similar ideological stance, while UNITA was able to secure the support of the South African government. The United States sided with the increasingly inefficient FNLA, stationed in the north of Angola.

Opposition leader Jonas Savimbi (centre right) with members of the UNITA armed forces - Source: www.angola24horas.com

Opposition leader Jonas Savimbi (centre right) with members of the UNITA armed forces - Source: www.angola24horas.com

A Brief Account of the Conflict

Subsequent to the Portuguese withdrawal from Angola, the Cuban- and Soviet-backed MPLA had secured control of Luanda – Angola’s capital city – and declared itself as the new government of independent Angola. Bolstering its position was the fact that it had received support and recognition from several other African countries; in 1969 the Organisation for African Unity (OAU) referred to the MPLA as the only truly representative party of Angola, and in 1976 the MPLA was formally recognised by the OAU as the legitimate government of independent Angola. The period between 1975 and 1976 was characterised not only by the withdrawal of the Portuguese, but also by the arrival of Cuban forces and the South African invasion into Luanda. Additionally, this period saw the defeat of the FNLA and the rise of UNITA as challengers to the MPLA’s self-established rule.

Subsequent to the Portuguese coup the FNLA’s internal support had already deteriorated considerably, although it maintained steady relations with Zaire and was thus well armed. This led the FNLA to attempt a forceful overthrow of the MPLA in Luanda, although the MPLA, backed by Cuba and the Soviet Union, deflected the onslaught and subsequently turned their antagonism towards UNITA. While the weakest in terms of military strength, UNITA harboured the greatest potential for electoral support, thus threatening the MPLA’s position of power. The FNLA and UNITA established a rival government in Huambo, pleading assistance from the South African forces to aid in ousting the MPLA. The MPLA retaliated with an influx of around 40,000 to 50,000 Cuban troops who succeeded in forcing out the internationally isolated South African troops, thus gaining control over the provincial capitals. The Cuban troops remained stationed in Angola as a means of maintaining stability and warding off further South African attacks. In 1977 the MPLA established itself firmly as a Marxist-Leninist party, pursuing a economic communism. The result of this, however, was disastrous, and Angola’s saving grace came in the form of its externally managed oil industry which prevented total economic and military collapse. The death of President Augustinho Neto in 1979 led to the inauguration of the MPLA’s former minister of planning, José Eduardo dos Santos.

Signing of the peace agreement between UNITA and the MPLA, ending a 27-year civil war in 2002 - Source: news.bbc.co.uk

Signing of the peace agreement between UNITA and the MPLA, ending a 27-year civil war in 2002 - Source: news.bbc.co.uk

In the meantime, the FNLA grew weaker in exile. UNITA, however, secured foreign support and established itself as an effective guerrilla army. In addition to aid from the US, UNITA was also supported by South Africa. On May 12, 1980, the SADF launched an attack on Cunene Province and was accused by the Angolan government of inflicting civilian casualties. Nine days later, the SADF again launched an attack, this time in Cuando-Cubango, incurring threats of military retaliation by the Angolan government. Disregarding these warnings, the SADF undertook a full-scale invasion through the two invaded provinces on 7 June, eradicating Namibia’s SWAPO operational command headquarters in the process. South Africa’s actions were condemned by the UN Security Council and Zaire, and Cuba reacted by increasing its forces from 35,000 in 1982 to 40,000 in 1985.

Although UNITA received military aid from the US beginning in 1985, thus rendering its campaigns more effective, the newly-named MPLA-PT launched large-scale military campaigns against UNITA in 1987 which resulted in a stalemate as neither side was able to gain the upper hand, and war engulfed the country. In September of 1987 the Battle of Cuito Cuanavale took place as the Armed Forces for the Liberation of Angola (FAPLA – the armed wing of the MPLA, which eventually became the official armed force of Angola when the MPLA assumed power) advanced into Angola via Cuito Cuanavale in an attempt at flushing out and destroying UNITA’s guerrilla forces. The SADF – at that stage still mandated to protect and support UNITA – intervened in the attack and halted the advance of FAPLA and its Cuban allies, resulting in a temporary stalemate.

In 1988 South Africa agreed to grant independence to Namibia and cease support to UNITA in exchange for the withdrawal of Cuban troops from Angola. Sceptical of this agreement, the MPLA-PT launched an attack in an attempt to capture Mavinga airfield from which it would be able to attack UNITA headquarters. Evidently, the MPLA-PT had underestimated the strength of UNITA and was forced to assume a conciliatory demeanour as UNITA grew increasingly effective in its military pursuits and attacks on oil installations. June 1989 saw negotiations between Savimbi and dos Santos with the aim of reaching a ceasefire agreement. The agreement, however, broke down very soon after it was established.

This period coincided with the international breakdown of communism which also resulted in deteriorating support of Eastern Europe for the MPLA-PT. This further spurred negotiations for the establishment of a new constitution and the abandonment of a one-party state. The MPLA veered away from its orthodox Marxist-Leninism and abandoned the ‘Partido Trabhalhista’ (PT) at the end of its name. After a (mostly) free and fair election in which the MPLA received the majority of votes, UNITA accused the leading party of election fraud and resumed civil war. UNITA representatives in Luanda were massacred in what was speculated to have been a government-endorsed uprising.

By 1992 UNITA had gained control of around two thirds of the country, including resource-rich diamond mines used to fund the war.

Fighting continued as the MPLA government gained increasing international support and recognition from the US, the UK as well as South Africa. Pressure mounted for the UNITA and the government to reach a peaceful solution, but UNITA was not complying. It incurred sanctions by the UN after it broke a ceasefire agreement. On 20 November 1994 the Lusaka Accord was signed by both parties in an attempt to reach a compromise; UNITA would cease all fighting, and in return it was to be incorporated into the government. The agreement was complicated by continuing tensions, aggravated by the refusal of Savimbi in 1997 to attend the ceremony in which UNITA members joined with the MPLA government. Compounding these problems was the regime breakdown in the Democratic Republic of Congo, wherein UNITA supported the government due to former ties while the MPLA government supported the rebel faction led by Laurent Kabila.

Continuing tensions eventually led to the expulsion of the UNITA delegates from government.

The assassination of Savimbi on 22 February 2002 eventually led to negotiations between UNITA and the MPLA, resulting in a peace agreement in April of 2002 and bringing to an end a 27-year civil war.

Signing of the Lusaka Protocol in Zambia. MPLA President Eduardo dos Santos (right) with United Nations special representative, Alioune Blondin Beye (left). - Source: exhibitions.nypl.org

Signing of the Lusaka Protocol in Zambia. MPLA President Eduardo dos Santos (right) with United Nations special representative, Alioune Blondin Beye (left). - Source: exhibitions.nypl.org

How was the conflict funded?

UNITA

External support played a major role in the funding of Angola’s civil war, and one consequence of the Cold War was the flow of Western funding to UNITA. During the 1980s, UNITA was supplied with US$80-million in arms, military training and logistics by the South African government, while the South African Air Force contributed regular drops of arms, ammunition, medicine and food to UNITA troops. Additionally, UNITA troops received varying support from other African countries; UNITA troops underwent training in Senegal, Tanzania and Zambia in the 1970s, and received financial and military aid from Egypt, Morocco, Senegal, Somalia and Tunisia. It was also reported that Israel contributed aid and training in Zaire, while several Arab states such as Saudi Arabia and Kuwait supplied support valued at around US$60 to US$70-million per year. The United States’ Central Intelligence Agency was speculated to have supplied between US$15 million and US$20 million annually in weapons, medicine, logistics and training.

During the power struggle between UNITA and the MPLA, UNITA managed to fund its military actions through the sale of diamonds valued at US$3.72 billion. In reaction to this, the United Nations Security Council passed resolution 1173 in 1998 which banned the purchase of diamonds from Angola.

MPLA

While UNITA secured external funding through the sale of Angola’s diamonds, the MPLA was receiving the bulk of its funding from the USSR, Cuba and the People’s Republic of Congo. When in 1974-1976 South Africa intervened on behalf of the FNLA and UNITA, Cuba aided the MPLA by sending thousands of troops who remained stationed in Angola throughout the civil war. While a UN arms embargo in the 1990s prevented the sale of arms to Angola, dos Santos turned to a French acquaintance – the French Socialist Party’s expert of Africa, Jean-Bernard Curial – who subsequently persuaded the son of the former French president, Francois Mitterand, to assist. Jean-Cristopher Mitterand introduced Curial to Pierre Falcone who had in the past arranged weapon sales for the French government. Together with a Russian ex-KGB colonel, Gaydamak, Falcone allegedly established a front-company in Eastern Europe which acted as a means to ship military equipment to Angola. This included tanks, armoured vehicles, weapons and ammunition. Evidence of Falcone’s transactions were later found, supporting the charges that Mitterand had received 14 million francs for arranging the deals. Supposedly, the Angolan government secured US$47 million worth of ammunition and artillery on 7 November, 1993, which was then received in December. In 1994, aircraft and tanks to the value of US$463 million were purchased.

Aside from external funding and aid, the exploitation and external trade of Angolan oil and diamonds (not already secured by UNTA) largely contributed to the MPLA’s finances.

FNLA

During the civil war period the FNLA received support from several external sources. France supplied troops and presented the FNLA with a loan of 1 million pounds sterling, without interest, while the US financially supported the FNLA by directing one-third of its Zaire budget to both the FNLA and UNITA. FNLA leader, Holden Roberto, secured funding from Israel after visits in the 1960s, and FNLA troops were sent to Israel for training. Arms were supplied to the FNLA by Israel during the 1970s through Zaire. Additionally, the FNLA received support (arms) from the People’s Republic of China in 1964.