The establishment of Drum Magazine in the 1950s, notwithstanding the newly-elected Nationalist Party’s policy of Apartheid, reflected the dynamic changes that were taking place among the new urban Black South African – African, Indian and Coloured – communities.

The magazine became an important platform for a new generation of writers and photographers who changed the way Black people were represented in society. This year marks the magazine’s 60th anniversary, which we are celebrating by publishing new material and key profiles over the next month.

The magazine, initially established as ‘The African Drum’ by journalist and broadcaster Robert Crisp, was not at first financially successful. It was taken over by Jim Bailey who, with the assistance of a team of writers and photographers, re-designed and rebranded the magazine, thereby making it more dynamic. Drum was so successful that Bailey used its urban, racy style to produce a number of East and West African editions of the magazine.

The magazine, initially established as ‘The African Drum’ by journalist and broadcaster Robert Crisp, was not at first financially successful. It was taken over by Jim Bailey who, with the assistance of a team of writers and photographers, re-designed and rebranded the magazine, thereby making it more dynamic. Drum was so successful that Bailey used its urban, racy style to produce a number of East and West African editions of the magazine.

A brief history of ‘Drum’

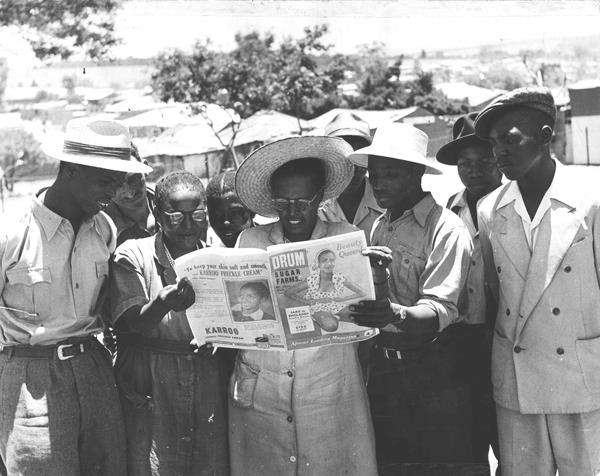

'In the teeming Negro and coloured shantytowns of Johannesburg, where newspapers and magazines are a rarity, a truck piled high with magazines rumbled through the unpaved streets last week. Wherever it stopped, hundreds of people swarmed about it, buying the magazine: The African Drum.' - extract from 'South African Drumbeats', TIME Magazine, 1952

The quote above suggests the popularity of the magazine that was to become known simply as Drum. However, the true reach of the magazine surpassed merely 'hundreds' of people, and became the most widely read magazine in Africa at the time. A 1959 article in Time magazine, entitled 'Drum Beat in Africa', stated that 240,000 copies of Drum were distributed across Africa, to countries like Kenya, Ghana, Nigeria and Sierra Leone.

The founding of Drum

First known as 'The African Drum', the magazine was launched by Robert Crisp, a journalist and broadcaster, supposedly to depict Black South Africans as 'noble savages'. The South African government allegedly sent copies abroad to make evident their success in managing the 'Bantu'. The content consisted mainly of tribal preaching and folk tales, and despite a readership of about 20 000, the magazine was not financially successful.

It was only when Jim Bailey – a former RAF pilot and the son of a South African mining baron – took over the magazine in 1951 that the publication grew. Bailey soon moved the magazine's headquarters to Johannesburg and re-named it Drum. The image of the magazine was transformed, and its content began highlighting urban black culture. The magazine became an important platform for emergent African nationalist movements.

Anthony Sampson, a friend of Bailey's from Oxford, was appointed editor, and under his leadership the magazine continued to grow and widely influence the new urban black culture.

To ensure that the magazine reflected Black life, they established an editorial board that included some of the leading political and cultural figures of the time: Joe Rathebe, Dan 'Sport' Twala, Dr Alfred Xuma and Andy Anderson. The board met once a month to generate ideas for new articles. The few staff members at this time consisted of a secretary, Sampson and sports editor Henry Nxumalo, who later became known as 'Mr Drum'.

Drum writers and photographers

As there were no educational facilities for black journalists and photographers at this time, many attached themselves to this publication as it allowed them to practise their craft. There were few magazines like Drum, and it attracted those interested in writing and photography and allowed them to develop their skills.

Photography was an especially important component of Drum's success, especially because photography served as an accessible and 'realistic' means with which to document protest action, and appeal to a largely illiterate readership. Drum's picture features – bright covers, jazz, girls and crime stories – appealed to readers, and the magazine's circulation increased.

Some of the first photographers included: Jurgen Schadeberg, an investigative photographer who later became the photo editor of the magazine; Bob Gosani, who started off at Drum as a messenger, but was later moved to the photographic department, where he became Schadeberg's darkroom assistant, and went on to become one of the magazine's best photographers; and Peter Magubane, who was hired in 1955 as a driver and a messenger, but over time became more interested in photography, and was eventually transferred to the photographic department.

This group was later joined by Ernest Cole, Alf Kumalo, Victor Xashimba, Gopal Naransamy, Chester Maharaj, GR Naidoo and others.

In some instances, Drum photographers had to develop tactful methods of obtaining photographs to avoid the wrath of white officials and the confiscation of their equipment. In one such instance photographers Bob Gosani and Arthur Maimane posed as white secretary Deborah Duncan's 'lackeys' in order to obtain photographs to complement Henry Nxumalo's first-hand account of oppressive prison conditions.

Drum writers included Peter Abrahams, Alex la Guma, Es'kia Mphahlele and Richard Rive. All wrote compelling stories, often using satire and irony in their depictions of Black South African life. They went on to achieve international recognition.

Other writers included Todd Matshikiza, who was celebrated for his wit, and employed as the music reviewer. Can Themba, a teacher in Sophiatown, won a Drum writing competition and was offered a job as a writer for the magazine. Towards the end of the 1950s, Lewis Nkosi and Nat Nakasa joined the Drum team. The writers used the language of American writers and movies, and created a fast, slangy street talk that few have been able to imitate. Nakasa later established a literary magazine called The Classic and won a Nieman Fellowship to study journalism in the United States. He left South Africa on an exit permit and was unable to return home. Isolated from his home country, he committed suicide a little more than a year later.

At Drum, aspiring journalists and photographers could chalk up hands-on experience and a relevant education, and became known as graduates of the 'Drum school'. Drum also provided temporary relief from a life of harsh discrimination, as the integrated staff environment at the magazine's offices was relaxed and free from segregation.

According to Magubane, 'Drum was a different home; it did not have apartheid. There was no discrimination in the offices of Drum magazine. It was only when you left Drum and entered the world outside of the main door that you knew you were in apartheid-land. But while you were inside Drum magazine, everyone there was a family.'

Drum, a political publication?

In March 1952, Drum published its first major story, entitled 'Bethal Today'. The eight-page article was written by 'Mr Drum', and was a sell-out success. Nxumalo posed as a labourer on a farm in Bethal in order to gain material for the story. What he encountered was gross abuse by 'boss-boys' with whips, and miserable living conditions.

Photographs taken by Schadeburg complemented the 'Bethal Today' story, and provided undeniable proof of these detestable conditions. The pictures compelled the government to enforce minor changes at farms in Bethal.

Although the intention of Drum was not to get involved in political issues, the editorial board felt that publishing the magazine would be meaningless and incomplete without reference to political issues, an inherent part of Black South African life.

Following 'Bethal Today', many stories of atrocities were printed in the magazine, which also featured an edition with an eight-page photographic essay on the 1952 Defiance Campaign. The edition sold 65 000 copies, clocking up a new circulation record. Drum continued to cover apartheid atrocities and political issues during the 1950s; among them the Sophiatown forced removals and the Treason Trial.

Although it opposed racism and apartheid, some important aspects of the Liberation Struggle were not featured. Jim Bailey did not approve the publication of any reports or photographs of the Sharpeville massacre, nor the terrible working and living conditions of migrant workers on the mines – reportedly due to his father's involvement in the gold mining industry. The magazine has since been accused of not reporting adequately on the political events of the time.

However, Drum was an important vehicle for voicing resistance during the 1950s – from the Defiance Campaign to the Sharpeville Massacre in 1960. It served as a means to unite and mobilise resistance, an important example being the photographs that accompanied Nelson Mandela's statement, 'We Defy', in the August 1952 issue.

According to The New History of South Africa, 'The Black press helped to extend the [Defiance] campaign's impact, particularly given the advent of photojournalism with the appearance of Drum magazine in 1951.'

Drum also documented the lives of integrated communities and multiracial interactions that were not depicted in other publications. One such example were images of White people in shebeens (informal drinking establishments) by Ranjith Kally in 1957.

A recent photographic exhibition at the Market Photo Workshop, entitled 'The Indian in Drum Magazine in the 1950s', displayed several photographs that documented the 'Indian experience' in South Africa. This is testament to the enduring legacy of Drum magazine in contemporary South Africa. Drum not only gave the oppressed a vehicle for expression during the 1950s, but has become an archival source that exposes and celebrates lesser-known aspects of our past.

Drum today

In 2004, the story of Drum was made into a Hollywood feature film of the same name, starring Taye Diggs as journalist Henry Nxumalo. The plot follows the story of Nxumalo's life, and documents the rise of Drum and life in Sophiatown during the institutionalising of apartheid in South Africa in the 1950s.

The movie was directed by Zola Maseko, who originally intended to tell the story in the form of a six-part television series entitled 'Sophiatown Short Stories'. Although not a major box office success, the movie was generally well received and won the 'Best South African Film' award at the Durban International Film Festival.

Drum continues to be published in South Africa under media conglomerate Media24. Still focused on providing relevant content for Black South Africans, Drum has become more orientated towards market news, entertainment and feature articles, with less focus on political issues.

Drum is the sixth largest consumer magazine in Africa, and along with sister publications Huisgenoot and YOU, forms an integral part of the South African popular media landscape. Once a resounding voice of resistance, Drum is considered part of every black South African's daily life and remains true to the words of its current tagline: 'The Beat Goes On'.