This article was written by Nicole Dellaportas and forms part of the SAHO and Southern Methodist University partnership project

Women’s Role in the Negotiations

Women played a major role in both politics and negotiations during the struggle against apartheid. Women helped transform South Africa into a new, free country where people now have a voice and freedom from the government. The apartheid struggles date back to the 1940s, and women were immediately involved even before then through the Bantu Women’s League in 1931. This was the start of women promoting their agenda through formal organization. After the start of apartheid, in 1943, women were officially allowed into the African National Congress (ANC). In 1948, they created a women’s organization call the ANC Women’s League (ANCWL). These political groups really gave women a role in the struggle. Women were active in their organizations and taking a stand during apartheid through protests and boycotts until 1960, when both the ANC and ANCWL were banned. Women were involved for nearly fifty years before the development of a new just government. They devoted their lives to the advancement of a new nation. The elections in 1994 created an opportunity for women to resolve and negotiate the troubles they have been facing since the start of apartheid. In the early 1990s, there were a number of negotiations held to address these problems, known as CODESA. Gender equality was one of the main arguments among these multi-party conferences. With the new elections happening, women wanted a role in the new government that was equivalent to men. Overall, the negotiations were successful in making the new South African government equal, according to Speak magazine:

‘Women’s efforts win the Gender Equality Clause in the new constitution of the country, so high a proportion of women in parliament that South Africa now ranks number four in the world in this respect, with 106 of the 400 MPs being women, and the putting into place of ‘gender machinery’ at various levels of government in order to advance gender equality.’ (SPEAK, 1982-1977)

The many struggles women endured in South Africa faced throughout history caused women to become politically involved. The difficult journey they endured during apartheid helped women take action by creating organisations and then getting involved in the 1990s negotiations. In the end, women were given an equal role in the new government because they never stopped pursuing their beliefs.

The Start of the ANC

The National Party was the South African primary political party of the government during the era of apartheid. The government refused to negotiate with Black people throughout their supremacy from 1948-1994. This made the people of South Africa take action and protest for freedom. With the new government came new laws that the people of South Africa disagreed with. People trying to create a voice led to the establishment of many groups including the ANC, ANCWL, Federation of South African Women (FSAW) and Women’s National Coalition (WNC). In 1943, women were allowed to join the ANC and in 1948 they created the ANCWL. An author described the ANCWL, ‘The essence of the ANCWL was to mobilise women to play a more meaningful role in the liberation struggle, and to watch for and resist any racist legislation directed against them as women.’ (Brooks, 2003) The ANCWL was the first women’s group to take an initiative against apartheid.

In June 1952, small groups decided to start rebellions against the new policies made by the National Party. A person who took part in the Defiance Campaign explained the time as, ‘The period culminated in the Defiance Campaign, the largest scale non-violent resistance ever seen in South Africa and the first campaign pursued jointly by all racial groups under the leadership of the ANC and the South African Indian Congress (SAIC).’ (Role of Women, 1980) A number of revolts took place in Johannesburg, Port Elizabeth, and all over South Africa. Over 10,000 volunteers were involved in the Defiance Campaign and about 8,000 of them were imprisoned by the end of December. The acts of defiance included a march around Johannesburg, where the protestors refused to carry permits on them. A group also went in the European section of a railway station. Women had a major role in the defiance campaign as well.

‘Women were prominent in many of these defiant incidents.Florence Matomela was among 35 activists arrested in Port Elizabeth and Bibi Dawood recruited 800 volunteers in Worcester.Fatima Meer, an Indian woman, was arrested for her role in the unrest and was subsequently banned.Another woman to come to the fore during the Defiance Campaign was Lilian Ngoyi, who later became president of both the ANCWL and FSAW.’ (The Turbulent 1950s, 2001)

Women were actively starting to get involved in political groups and wanted to create their own only women organization. Some of the major progress later in the 1990s was mainly due to the actions of women.

The Role of the FEDSAW

The Federation of South African Women (FEDSAW) was created in 1954 to create the first diverse organization for women in South Africa. Women of all colors and races were allowed to join the FSAW.

‘One hundred and forty-six delegates, representing 230,000 women from all parts of South Africa, attended the founding conference and pledged their support for the broadly-based objectives of the Congress Alliance.The specific aims of FSAW were to bring the women of South Africa together to secure full equality of opportunity for all women, regardless of race, colour or creed, as well as to remove their social, legal and economic disabilities.’ (The Turbulent 1950s, 2001)

The first major conflict FEDSAW sought to improve was freedom to go where they choose. The National Party put restrictions on all travel by women and this was called the “passbook laws.” The FSAW decided to carry out a protest at Pretoria. One of the fliers used to raise awareness stated, ‘By standing united, protesting with one voice and organising all areas around this wicked law, the women are trying to achieve the abolition of the pass law system with its vicious attack on their liberty.’ (Anti-Pass Flyer, 1957) The Pretoria City Council opposed the march and they put a stall on public transportation in order to delay and hopefully cancel the protest. This did not stop the FSAW, and about a group of 2,000 women gathered at Pretoria to speak their mind regarding the passbook laws. Overall, the protest was a success and it was a sign of hope for not only the FSAW, but for women across the nation.

After the passbook protest, the issue became the focus of the FSAW. Dedicating most of their time to this cause, a strategy was created and the FSAW decided a march at Pretoria was the optimum option. On 9 August 1956, About 20,000 women gathered from all over South Africa to take part in the march. Women dressed in South African colors and stood in silence for long periods of time and when they were not being silent they sang their favorite songs. South African History Online (SAHO), the largest independent research institute in South Africa described the march as, ‘The Women's March was a spectacular success.Women from all parts of the country arrived in Pretoria, some from as far afield as Cape Town and Port Elizabeth.They then flocked to the Union Buildings in a determined yet orderly manner.’ (The Turbulent 1950s, 2001) The leaders of the march left signed documents at the prime minister’s office. Although the prime minister didn’t even look at the papers, South African women considered the march a huge success and were thrilled about it.

A few years later in 1960, organizations including the ANC, PAC and FSAW, agreed it was necessary to take more non-violent actions regarding the pass laws. They decided to go to police stations around the country without carrying their passbooks on them. On 21 March 1960, about 5,000 women and men sang and protested at the Sharpeville police station. The march was going smoothly and it was successful, until a police officer claimed to be stoned by one of the protesters. A protester at the station said, ‘The firing lasted for approximately two minutes, leaving 69 people dead and, according to the official inquest, 180 people seriously wounded.’ (Sharpeville, 2001) The police at Sharpeville were wrongful in opening fire against the protesters. A witness at Sharpeville explained the environment, ‘I saw no weapons, although I looked very carefully, and afterwards studied the photographs of the death scene.While I was there I saw only shoes, hats and a few bicycles left among the bodies.The crowd gave me no reason to feel scared.’ (Sharpeville, 2001) It wasn’t until 1986 that the passbook laws were finally abolished.

Women in the Negotiations of the 1990’s

After the Sharpeville Massacre, people were scared and traumatized by the actions of the National Party. Although scared, many victims were upset and still chose to fight for their freedom. The National Party viewed all of the events as threats and in 1960 they decided to place a ban in of the ANC and ANCWL. The National Party took extreme action in making sure the acts of defiance come to an end. South Africans had no options except to convene underground, which could lead to arrest or exile. Major changes in government were not made until the 1990s, when women were involved in the political negotiations of a new and transformed government. Women played a huge role in the involvement of the new government, and between the years 1991-1993 they helped repair their country. During the beginning of the negotiations, women worked together to create the Gender Advisory Committee for the Convention for a Democratic South Africa (CODESA). They hoped the committee would promote equality in the government during the negotiations. In 1992, over 60 organisations all came together to commence the Women’s National Coalition. At the first meeting, one of the leading women began the speech by saying, ‘A future non-sexist South Africa depends on us.No one is going to give it to us.We have been banging on doors for generations and nobody has opened them.Now we have to open the doors through the voices of millions of South African women.’ (Speak, 1992) Women groups were coming together from all around South Africa and they decided to bring all of their requests together to form one charter. The Women’s Charter launched in 1994, and commenced with the words, ‘As women and citizens of South Africa we are here to claim our rights.We want recognition and respect for the work we do in the home, in the workplace and in the community.We want full participation in the creation of a non-sexist, non-racist, democratic South Africa.’ (Speak, 1994) The women’s charter was a victory, but people realised the struggle was far from over.The time of the negotiations gave women a chance to request change, and it mainly focused on their role in the government.

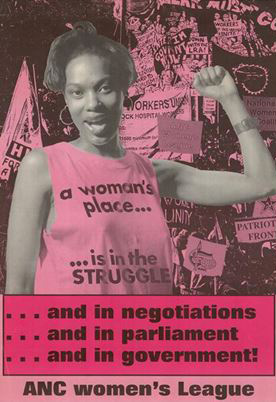

A woman's place... Image source

A woman's place... Image source

In 1994, the ANC was voted the new head of government in South Africa, with Nelson Mandela as president. The new parliament consisted of about one fourth women, and Frene Ginwala was appointed the speaker. Mandela promoted women’s equality greatly and even opened his initial speech with, ‘The objectives of the Reconstruction and Development Programme will not have been realised unless we see in practical terms the condition of women in South Africa changing for the better, and that they have the power to intervene in all aspects of life as equals.’ (Speak 1994) This was a sign of hope never seen in South Africa before. Women were not just involved in politics, but they were now involved in the formation of the new parliament.A statistic that shows the major improvements in a short time is, ‘In 1991, Codesa was made up of less than 5 percent women, and in 1994, ‘Women formed 27.75% of members of the National Assembly after South Africa's first democratic elections and this number has increased to 44% in 2009.’ (Nobrega, 2014) Gender equality has seen major progress both socially and politically and is still improving today.

The progress made in the last 20 years is almost unbelievable. The women of South Africa never gave up and they fought for what they believed in by performing many marches and protests. The women created a voice when many gave up. They created their success through many years of gaining support. They created prominent groups like the ANCWL and FEDSAW. Women expanded their groups to all races and all people in Africa who had their same beliefs. With the new parliament came many opportunities for women. Mandela knew the importance of equality and supported women’s rights throughout his time. In the end, the women of South Africa were successful in reaching their dreams. They were successful in giving women a role in politics. In the end, women’s role in the government was equal to men. Women’s hard work and strength in South Africa for many years led to freedom and a complete change in government. Women’s role in politics paved the way to a new South Africa.

Kagan, R., (1993). Election News from Africa African Women. [online] Available at https://www.aluka.org [Accessed 15 December 2014]|Patel D., (2006). List of Demands of African Women: Federation of South African Women 1954-1963, Johannesburg: Witwatersrand University Press.|Meer, S., (1982-1997). Women Speak: Reflections on Our Struggles, 1982-1997, Oxfam.|South African History Online (SAHO), (1991). CODESA I-Declaration of Intent [online] Available at https://sahistory.org.za [Accessed 5 December 2014]|South African History Online (SAHO), (1957). FEDSAW Anti-Pass Flyer [online] Available at https://sahistory.org.za [Accessed 2 November 2014]|Digital Innovation South Africa (DISA). ‘A woman’s place is in the struggle”¦’ Available at https://www.aluka.org [Accessed 14 December 2014]|African National Congress, (1980). ‘The Role of Women in the Struggle against Apartheid’ Available at https://www.anc.org.za [Accessed 1 November 2014]|Brooks, P., (2003). Empowering Women for Gender Equity.London: Taylor & Francis, Ltd., pp. 84-97.|Kimble, J. and Unterhalter, E., (1982). ANC Women’s Struggles, 1912-1982. United Kingdom: Palfrave Macmillian Journals, pp. 11-35.|Magubane, B., (2010). ‘The Turn to Armed Struggle’ in The Road to Democracy in South Africa, Vol. 1 [1960-1970], Pretoria: Unisa Press.|Nobrega, C., (13 March 2014). South Africa: Gender Equality and Morality as Citizenship. Available at https://www.opendemocracy.net [Accessed 20 November 2014]|South African History Online (SAHO), ‘History of Women's Struggle in South Africa’ Available at https://sahistory.org.za [Accessed 30 October 2014]|South African History Online (SAHO), ‘Sharpeville Massacre’ Available at https://sahistory.org.za [Accessed 20 November 2014]|South African History Online (SAHO), ‘The Turbulent 1950s - Women as Defiant Activists’ Available at https://sahistory.org.za [Accessed 19 November 2014]