International responses

The Sharpeville massacre was reported worldwide, and received with horror from every quarter. South Africa had already been harshly criticised for its apartheid policies, and this incident fuelled anti-apartheid sentiments as the international conscience was deeply stirred.

The United Nations Security Council and governments worldwide condemned the police action and the apartheid policies that prompted this violent assault.

The ANC Vice-President, Oliver Tambo, was secretly driven across the border by Ronel Segal into the then British controlled territory of Bechunaland. He was followed by Dr. Yusuf Dadoo, Chairperson of the South African Indian Congress and Chairperson of the underground South African Communist Party. Both were tasked with mobilizing international financial and diplomatic support for sanctions against South Africa. On 20 March Nana Mahomo and Peter Molotsi has crossed the border into Bechuanaland to mobilize support for the PAC.

International sympathy lay with the African people, leading to an economic slump as international investors withdrew from South Africa and share prices on the Johannesburg Stock Exchange plummeted.

Local responses

Dr. Verwoerd praised the police for their actions. Robert Sobukwe and other leaders were arrested and detained after the Sharpeville massacre, some for nearly three years after the incident. Sobukwe was only released in 1969.

In the aftermath of the events of 21 March, mass funerals were held for the victims. On 24 March 1960, in protest of the massacre, Regional Secretary General of the PAC, Philip Kgosana, led a march of 101 people from Langa to the police headquarters in Caledon Square, Cape Town. The protesters offered themselves up for arrest for not carrying their passes.

By the 25 March, the Minister of Justice suspended passes throughout the country and Chief Albert Luthuli and Professor Z.K. Matthews called on all South Africans to mark a national day of mourning for the victims on the 28 March. The call for a “stay away” on 28 March was highly successful and was the first ever national strike in the country’s history. In particular, the African work force in the Cape went on strike for a period of two weeks and mass marches were staged in Durban. In Cape Town, an estimated 95% of the African population and a substantial number of the Coloured community joined the stay away. Policemen in Cape Town were forcing Africans back to work with batons and sjamboks, and four people were shot and killed in Durban.

On the day passes were suspended (25 March 1960) Kgosana led another march of between 2000 and 5000 people from Langa to Caledon Square. The march was also led by Clarence Makwetu, the Secretary of the PAC’s New Flats branch. The march leaders were detained, but released on the same day with threats from the commanding officer of Caledon Square, Terry Tereblanche, that once the tense political situation improved people would be forced to carry passes again in Cape Town. The impact of the events in Cape Town were felt in other neighbouring towns such as Paarl, Stellenbosch, Somerset West and Hermanus as anti-pass demonstrations spread.

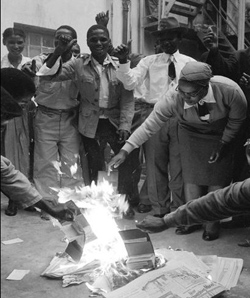

As an act of rebellion the passes were set alight, as seen in a picture by Ranjith Kally. Courtesy BaileySeippel Gallery/BAHA Source

As an act of rebellion the passes were set alight, as seen in a picture by Ranjith Kally. Courtesy BaileySeippel Gallery/BAHA Source

A few days later, on 30 March 1960, Kgosana led a PAC march of between 30 000-50 000 protestors from Langa and Nyanga to the police headquarters in Caledon Square. The protesters offered themselves up for arrest for not carrying their passes. Police were temporarily paralyzed with indecision. The event has been seen by some as a turning point in South African history. Kgosana agreed to disperse the protestors in if a meeting with J B Vorster, then Minister of Justice, could be secured. He was tricked into dispersing the crowd and was arrested by the police later that day. Along with other PAC leaders he was charged with incitement, but while on bail he left the country and went into exile. This march is seen by many as a turning point in South African history.

On the same day, the government responded by declaring a state of emergency and banning all public meetings. The police and army arrested thousands of Africans, who were imprisoned with their leaders, but still the mass action raged. By 9 April the death toll had risen to 83 non-White civilians and three non-White police officers. 26 Black policemen and 365 Black civilians were injured – no White police men were killed and only 60 were injured. However, Foreign Consulates were flooded with requests for emigration, and fearful White South Africans armed themselves.

The Minister of Native Affairs declared that apartheid was a model for the world. The Minister of Justice called for calm and the Minister of Finance encouraged immigration. The only Minister who showed any misgivings regarding government policy was Paul Sauer. His protest was ignored, and the government turned a blind eye to the increasing protests from industrialists and leaders of commerce. A deranged White man, David Pratt, made an assassination attempt on Dr. Verwoerd, who was seriously injured.

A week after the state of emergency was declared the ANC and the PAC were banned under the Unlawful Organisations Act of 8 April 1960. Both organisations were deemed a serious threat to the safety of the public and the vote stood at 128 to 16 in favour of the banning. Only the four Native Representatives and members of the new Progressive Party voted against the Bill.

In conclusion; Sharpeville, the imposition of a state of emergency, the arrest of thousands of Black people and the banning of the ANC and PAC convinced the anti-apartheid leadership that non-violent action was not going to bring about change without armed action. The ANC and PAC were forced underground, and both parties launched military wings of their organisations in 1961.