From the book: Book 5: People, Places and Apartheid commissioned by The Department of Education

By 10:30 on 16 June 1976, thousands of students had gathered in Orlando West to begin a protest march against the imposition of the Afrikaans language as the medium of instruction in Soweto's schools. More were on their way. The local police were totally unprepared for a march of this size. Eventually they opened fire, killing Hastings Ndlovu and Hector Peterson. The shootings sparked off days of riots and hundreds of deaths.

The Soweto revolt had begun.

The police on duty had no special training in crowd control and did not even possess a loudhailer. They first tried to use dogs and teargas, but students killed two dogs and most of the teargas canisters proved to be defective. Police claimed that students had thrown stones, and that they, the police, had fired warning shots in the air.

After Sergeant Hattingh fired the first fatal shot, chaos ensued. Student leaders were unable to disperse their followers. Students responded to the shootings with fury. Streets were barricaded, cars burned and two white officials killed. By lunchtime students were looting and burning government buildings and liquor stores across much of Soweto.

That afternoon the paramilitary riot police arrived. Their instructions were clear - shoot to kill; law and order should be maintained "at any cost". The police shot dead another 11 people before evening.

News of the events in Soweto sparked off protests in black townships across the country. Another 93 people were shot dead by police over the next two days. By the end of February 1977 the official death toll stood at 575 - 75 coloured, 2 white, 2 Indian AND 496 African. Many areas were affected - 22 townships in the Transvaal, 16 areas of Cape Town, 4 townships in Port Elizabeth and 9 other towns. Over the next decade and a half, students would join hands with trade unions, civic organisations and the external armed wings of the ANC and PAC to topple the apartheid regime.

Letter from Bishop Desmond Tutu to Prime Minister John Vorster, 8 May 1976

(abridged)

I am writing to you, Sir, because I have a growing nightmarish fear that unless something drastic is done very soon then bloodshed and violence are going to happen in South Africa almost inevitably. A people can take only so much and no more. The history of your own people which I referred to earlier has shown this. I wish to God that I am wrong and that I have misread history and the situation in my beloved homeland, my mother country South Africa. A people made desperate by despair and injustice and oppression will use desperate means. I am frightened, dreadfully frightened, that we may soon reach a point of no return, when events will generate a momentum of their own, when nothing will stop their reaching a bloody denouement which is “too ghastly to contemplate” to quote your words, Sir”¦. But blacks are exceedingly patient and peace loving. We are aware that politics is the art of the possible. We cannot expect you to move so far in advance of your voters that you alienate their support. We are ready to accept some meaningful signs which will demonstrate that you and your government and all whites really mean business when you say you want peaceful change. First, accept the urban black as a permanent inhabitant of what is wrongly called white South Africa with consequent freehold property rights. He will have a stake in the land and would not easily join those who wish to destroy his country. Indeed, he will be willing to die to defend his mother country and his birthright. Secondly, and also as a matter of urgency, to repeal the pass laws which demonstrate to blacks more clearly than anything else that they are third-rate citizens in their beloved country. Thirdly, it is imperative, Sir, that you call a National Convention made up of genuine leaders (i.e. leaders recognised as such by their section of the community) of all sections of the community, to try and work out an orderly evolution of South Africa into a non-racial, open and just society.

Source: Thomas Karis and Gail M. Gerhart, From Protest to Challenge, Volume 5. Stanford University, Hoover Institution Press, 1997, p.567.

Are there different analyses of the uprising?

The Soweto rebellion was initiated by school children in protest against the use of Afrikaans as a medium of instruction in schools. However, a combustible situation had been developing in Soweto since the mid-1960s as a result of an accumulation of various grievances. The Afrikaans-medium issue provided the spark for the explosion.

To understand the rebellion we need to trace the big social and economic changes that had been taking place in Johannesburg and Soweto over the previous ten years ”” what I call structural changes. We have to understand the way these changes affected the cultures and consciousness of various parts of Soweto’s population, the way a set of more limited educational grievances gave rise to the 16 June demonstration, and the way police reactions sparked widespread insurrections.

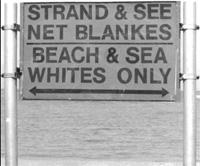

Petty apartheid signs in Cape Town, 1989.© Guy Tillim / South Photographs

Petty apartheid signs in Cape Town, 1989.© Guy Tillim / South Photographs

What was apartheid?

apartheid”” a system of segregation or discrimination on the basis of race. It was government policy in South Africa from 1948 to 1991.

grand apartheid”” the principles and policies that dealt with the broader political and economic aspects of the apartheid system, such as the creation of homelands based on ethnic or tribal divisions. These policies were at their height during the 1960s and 1970s.

petty apartheid ”” the principles and policies that dealt with the day-today aspects of the apartheid system, such as the pass laws, the ban on inter-racial marriage, the use of separate public facilities, and so on. Petty apartheid signs in Cape Town, 1989.

Different authors place different emphasis on various factors. Some highlight educational issues; some focus on structural changes in the economy and society; some concentrate on the political changes of “grand” apartheid; some stress the emergence of new youth subcultures in Soweto’s secondary schools in the mid 1970s; some emphasise the transformative role of Black Consciousness ideology and its associated organisations like the South African Students Movement (SASM); still others insist on the autonomousactions of the junior grades at several of Soweto’s schools. All of these factors need to be taken into account. It is our task to find the right blend.

autonomy”” freedom of action; independence

grand apartheid”” the principles and policies that dealt with the broader political and economic aspects of the apartheid system, such as the creation of homelands based on ethnic or tribal divisions. These policies were at their height during the 1960s and 1970s.

What are some of the structural reasons for the uprising?

Policy shift to grand apartheid Between 1954 and 1960 over 50 000 houses were built for Africans in Soweto. The rate of house building slowed down in the early 1960s and stopped completely in 1965. This did not mean that the demand for houses had been satisfied. The children of Soweto’s residents grew up, married and started families in the 1960s, so that by the mid-1970s an acute shortage of housing had developed.

Government policy on housing changed for political reasons. After the Sharpeville massacre and the banning of the ANC and PAC in March 1960, Prime Minister Hendrik Verwoerd and his government began to see urban Africans as a far bigger threat to white supremacy than had been previously imagined. Up until 1960 whites had accepted the idea of an African urban population with the right to live and work permanently in the towns. The government even gave migrant workers the opportunity to secure rights to permanent residence if they had worked continuously for the same employer for 10 years or in the same industrial area for 15 years.

After 1960 the government began to restrict and even remove rights enjoyed by urban Africans. In addition, fewer and fewer new houses, schools and police stations were built in African townships. Africans were told that they could enjoy political and civic rights only in African homelands like the Transkei and Bophutatswana. State revenue and resources were redirected from urban African areas to the homelands.

The policy shift in 1960 from a practical apartheid to a more dogmatic grand apartheid was therefore a turning point in its own right. It partly helps to explain the next turning point ”” the main turning point that we are discussing ”” the 1976 Soweto students uprising.

New repressive laws

Another change also occurred in the early 1960s. A series of repressive laws were enacted which began to turn South Africa into a police state. In June 1962 the General Laws Amendment Act No 76 (which came to be known as the Sabotage Act) was passed. It created the offence of sabotage; the penalties were the same as for treason, including the death penalty. (This was in response to the ANC and PAC’s move to armed struggle.) Almost a year later, in May 1963, the General Laws Amendment Act No 37 was passed. This law ”” which came to be known as the “90 Day Law” ”” permitted the detention for 90 days without a warrant of any person suspected of a political crime, without access to a lawyer.

Many detained under this Act were re-arrested at the end of the first 90 days. One thousand people were detained under this law over the next two years, and held in solitary confinement. From this point on, torture of detainees became routine. Up until then, a person could refuse to make a statement to the police. Now most prisoners broke under the brutal torture. Many were sentenced to life imprisonment. Many hangings took place in the course of the 1960s ”” 101 persons were hanged in that decade, far more than were executed in the next 20 years. By these means, popular resistance was broken in the early 1960s.

Economic changes

Repression was not the only reason for the quietness and submissiveness of Soweto’s residents during the 1960s. The 1960s were a boom time in South Africa, and particularly in Johannesburg. At the peak of this boom in 1963-1964, the economy grew at 8.5%. Between 1965 and 1969 foreign investment increased by over 60%, much of this in the manufacturing industry. Machine-based factories required semi-skilled labour rather than the unskilled labour of the past. Semi-skilled labour was generally better paid.

People who were not needed for work in the cities were labelled “superfluous appendages” and forced to go back to the homelands. They included widows, children, chronically sick people and the mentally ill.

Because of this and other factors, a small part of the prosperity of the “golden age” of the 1960s trickled down to black Sowetans.

From the early to mid 1960s black wages began to improve. The numbers of those employed in semi-skilled work doubled between 1960 and 1970. The average number of wage earners per family rose from 1,3 to 2,2 between 1956 and 1968, as wives found it easier to get jobs and children grew up and began to contribute to the family income. The wage gap between black and white workers narrowed across all sectors between 1964 and 1974, reflecting the improved wages of African workers on the Witwatersrand.

How did grand apartheid contribute to the uprising?

Rising incomes produced a more consumerist black urban culture in the 1960s, which also played a role in quieting political discontent. The government’s very success in diverting black opposition, however, created an attitude among its members which made sure that black opposition revived. Black silence encouraged the government and its officials to believe that the majority of Africans accepted apartheid and that only a handful of agitators ”” whom they had now silenced in various ways ”” were opposed.

This persuaded them to introduce a string of new policies and laws that had an increasingly hardline ideological, arrogant and unreasonable character.

Some of these were implemented during the prime ministership of Hendrik Verwoerd, who was assassinated in September 1966. Others were introduced under his successor, B.J. Vorster, the former Minister of Police.

In 1964 the Bantu Laws Amendment Act further tightened influx control. Previously, Section 29 of this Act had allowed the authorities to deport anyone declared “idle” out of the urban areas and into the homelands. However, the authorities had not been able to enforce this clause because they had not clearly defined what “idle” meant. Now it was defined as refusing employment three times and losing one’s job more than twice in six months.

influx control”” (under apartheid) the strict limitation and control imposed on the movement of black people into urban areas

appendage”” something attached to a larger or more important thing

superfluous”” unnecessary

Women were especially hard hit by the Act, being prohibited from entering the urban areas except on a visitors permit. Over the next three years the government ordered that widows, unmarried mothers, divorced women and deserted women were not entitled to housing, and that women born in a homeland who married an urban man were not entitled to permanent rights in the towns.

Pass raids netted tens of thousands of unfortunate urban residents disqualified in these ways, and convictions for pass offences nationally doubled from 384 497 in 1962 to 693 661 in 1967. Further attacks on African urban rights were mounted in 1968. First the government decreed that the right to hold home leases would end. Almost 10 000 homes in Soweto had been built or sold to residents under the 30- year leasehold scheme. Without the slightest consultation, these were abolished. In the same year, migrant workers were forced to return home at the end of their 12-month contract and to renew it in their homeland.

Because each contract lasted for only one year, this made it impossible for migrant workers to qualify for permanent status. Finally, the government passed a law which laid down a ratio of black to white workers (3:1). The aim was to force industries who employed large numbers of Africans, such as textile factories, into the so-called “border areas” close to the homelands.

These measures intended to reverse the flow of Africans into the cities.

Two of the main ways the government used to discourage Africans from living in the towns was restricting the scope for African professionals and entrepreneurs and placing a ban on the building and operation of African secondary schools. This tended to force black traders and students into their supposed homelands. In 1969 the already-limited rights of African traders in townships were restricted even further. Traders in the townships were prohibited from building or owning their own premises, and were not allowed to open up more than one shop or to do business “for any purpose other than that of providing for the essential domestic requirements of Bantu residents”. Shops had to be a certain size, could only trade within restricted hours and were only permitted to sell a very narrow range of goods. If an entrepreneur had any ambition, he or she was forced to pursue it in a homeland.

A similar policy applied to secondary education. Between 1962 and 1971 no new secondary schools were built in Soweto, and all resources for such purposes were channelled to the homelands. The number of African children enrolling at primary schools expanded much more rapidly than the resources allocated to this sector. Some classes contained over 100 students, and teachers were often forced to teach two shifts each day. Educational standards dropped, breeding growing dissatisfaction among pupils and contributing to the militant spirit that exploded in June 1976.

Clement Twala, who served in Soweto as a police auxiliary (commonly known as “blackjacks”) for the Johannesburg City Council, gives a striking account of how far the people’s spirit was crushed. Blackjacks were charged with duties such as arresting Soweto householders in arrears with rents. Twala remembered occasions when they would arrest 30 or more people for such offences.

“These people would move very peacefully without fighting back at all. We would move right behind them and they would never dream of running away. We were never scared that these people would turn against us. We didn’t carry guns. They feared punishment. It used to be a disgrace for any black person to be found defying the law then.”

Source: Philip Bonner and Lauren Segal, Soweto: A History. Johannesburg, Maskew Miller Longman, 1998, p.69.

Prime Minister Vorster dealt with conflicting opinions in his Cabinet far differently from his predecessor, Hendrik Verwoerd. Whereas Verwoerd had imposed his own inflexible view and would tolerate no dissent from his Cabinet, Vorster allowed his ministers greater freedom, to a point where they could be pursuing contradictory and even conflicting policies. In the end, this would prove fatal to his government.

In 1970 hardline ministers of the Vorster government took another decisive step in the direction of stripping urban Africans of their civic rights in the towns. In that year, the Bantu Homelands Citizen Act was passed. It compelled all urban Africans to become citizens of whatever ethnic homeland they were supposed to have originated from, whether or not they had ever set foot there. The practical implementation of this policy was postponed until the mid-1970s when Transkei and Bophuthatswana became fully independent. With this, the thinking of the dominant section of Vorster’s cabinet became plain.

In yet another effort to tighten its grip on the townships, in 1972-1973 the government removed responsibility for the administration of black urban townships from adjacent white municipalities and placed them under what were termed Bantu Administration Boards which fell directly under the authority of the Bantu Affairs Department. The West Rand Administration Board (WRAB), which managed Soweto, was headed by the hardliner, Mannie Mulder. Financial subsidies previously provided by city councils were withdrawn. Services in an increasingly overcrowded Soweto deteriorated alarmingly. The mounting volume of complaints from Soweto’s residents were brushed aside by unsympathetic, inexperienced and often racist WRAB officials.

Minister of Bantu Affairs M.C. Nel unapologetically announced,

“One of the chief aims of my department is to bring to fruition the state policy of reversing the stream of Bantu to the white areas and to bring about an exodus of these Bantu to the homelands”¦. I ask all of you to widen your horizons to become nation builders rather than township builders.”

The absurd actions to which grand apartheid policies could lead were fully exposed when the Bantu Affairs Department pressed the Johannesburg City Council to support a scheme in which 23 000 Zulu-speaking families in Soweto would be relocated to the proposed township of Waay Hoek on the outskirts of Ladysmith in Natal. The idea was that the male workers of these families would be accommodated in Soweto’s hostels during the week and then would commute 400 kilometres each weekend by Japanese highspeed electric train. It should be no surprise that black Sowetans began to see themselves as being increasingly under siege from an unsympathetic and even hostile government. This, too, contributed to the anger and frustration that fed the 1976 rebellion.

What was the link between structural changes and political action?

Ideology and dogma cannot indefinitely ignore material pressures and economic realities. After a brief drop, the economic boom of the 1960s extended into the 1970s. As industry expanded, there were not enough whites to meet the growing demand for skilled jobs. At the same time the low and deteriorating standards of black education meant that the skills shortage could not be met from that source. Employers and employersympathetic newspapers such as the Sunday Times and the Rand Daily Mail began to agitate for better education and training for the black urban workforce.

Even though much of government policy was moving in the opposite direction, a more liberal section of the Cabinet began to support this demand. In 1972 the government reluctantly accepted that new secondary schools would have to be provided in the urban areas. This was done, and the number of secondary school pupils rose quickly.

The sudden growth in the number of secondary and primary school pupils in Soweto meant that a major change had taken place in the structure of Soweto’s population, and especially of that of its youth.

Across the country the number of African secondary school pupils jumped up from 122 489 in 1970 to 318 568 in 1975. The numbers of secondary schools in Soweto grew especially fast.

Forty new secondary schools were built between 1972 and 1976; secondary school enrolments increased from 12 656 in 1972 to nearly 35 000 in 1976.

However, structural changes do not automatically lead to new social and political consequences. Political changes come when people begin to think and behave in a different way ”” that is, when human consciousness, human cultures and human identities change. Such a change of consciousness and identities occurred in Soweto in the mid-1970s, and provided the link between structural changes and political action.

What emerged as a result of the growth of secondary schooling was a new youth subculture in Soweto ”” a new collective identity. Up until this point most of the youth who left primary schools were unable to secure a job, often until their early 20s.

They commonly spent the several years in between as members of youth gangs, hanging around the streets. Youth gangs were usually localised and extremely territorial. They fought constantly among themselves ”” over women, street corners, shops, cinemas and gambling schools.

The focus of their lives was pleasure and survival. Such divided, localised, self-indulgent groups often lacked any wider political consciousness, and were unresponsive to the black consciousness ideas that were taking root in other sectors of Soweto’s black population.

The growth of secondary schools and the emergence of a new collective youth identity which drew its members from across a number of gang neighbourhoods constituted a major challenge to gangs such as the Hazels and Dirty Dozens. They now targeted school pupils, especially schoolgirls, as they made their way to school. Pupils responded with mass resistance and retaliation, which further reinforced their collective consciousness and solidarity. This in turn created a much more promising environment in which a broader political consciousness could take root and grow.

Other developments which contributed to a school-going youth consciousness and solidarity were wider structural changes in the South African economy. Massive increases in oil prices (following the Arab-Israeli War) in 1973-1974 pushed the world economy into deep depression, combined with rapid inflation. In 1975 a sharp drop in the gold price aggravated South Africa’s economic difficulties.

School-goers suffered from these developments in two ways. First, as the economy stopped growing secondary school leavers were unable to find jobs and were dumped into the ranks of the unemployed. Second, a cashstrapped government attempted to save money by reducing its expenditure on the African majority, and above all on the residents of the African townships. All township services and amenities suffered, including the schools.

In an attempt to save money the Bantu Education Department decided to reduce the number of school years from 13 to 12. Standard 6 (Grade 8) was selected as the victim. At the beginning of 1976 pupils completing Standard 5 were able to proceed directly to secondary school. In that year, therefore, Standard 6 and Standard 5 graduated into secondary schooling together. Overcrowding reached new heights. Educational standards declined further. The injustices of Bantu education were becoming

increasingly intolerable.

As the leading spokesperson of black consciousness, Steve Biko, put it, its aim was:

“to instil the idea of self-determination, to restore feelings of pride and dignity to blacks after centuries of racist oppression. It is an attitude of mind, a way of life. It is a realisation that the most potent weapon in the hands of the oppressor is the minds of the oppressed.”

How did black consciousness contribute to the uprising?

Within this anxious and angry environment, a new political grouping and ideology made its appearance. It was generally described as black consciousness. Its main vehicles were the South African Students Organisation (SASO) launched at the University of the North in 1969, the Black People’s Convention (BPC) formed in 1972, and the South African Students Movement (SASM) which emerged out of the African students movement in the same year. Black consciousness made a massive contribution to changing the attitudes of black South Africans.

Black consciousness marked a radical break with the resignation, the fear and the apathy of the 1960s. One of its main contributions was the injection a new kind of courage and self-assertion among its members ”” a kind of courage which would help them to brave assault and torture, and which would lead them to refuse to be intimidated, whatever the threat.

Opinions differ as to what kind of impact black consciousness and its school pupil organisation SASM had on the climate of opinion among Soweto’s school-goers and how much it contributed to the 1976 students uprising. By 1973 SASM had branches in nine schools in Soweto.

Resources were scarce, however. The organisation was set back in March of that year by the banning of the top leadership of the South African Students Congress (SASO) as well as Mathe Diseko, the national secretary of SASM. SASM revived in 1974, encouraged by the military coup in Portugal in April 1974 and the decolonisation of Mozambique. As SASM leaders began to gain confidence, they organised public meetings at which militant speeches were given.

As Tebogo Mohapi recalls,

“SASM had reached a point where we couldn’t hide from students and we gradually became more and more conspicuous in the schools”¦. Towards the end of my Standard 8 year we’d clearly gathered a large number of students at my school. Some of us started rotating from school to school to talk to the students. Corporal punishment was one of the basic projects of SASM ”¦ we’d also talk about Bantu Education as a poison that enslaved us”¦. This was how we organised SASM into a fully-fledged organisation”.

It is difficult to know how many students were drawn into SASM. It does seem clear, thought, that it did have some impact on the general political atmosphere in some schools.

What were the final events leading to the uprising?

It was against this background that Minister of Bantu Affairs and Development, M.C. Botha, announced the compulsory use of Afrikaans (instead of English) as the medium of instruction in half the school subjects from Standard 5 onwards. This was another example of a hardline authoritarian minister enforcing a policy which was inconsistent with the slightly more reformist path that other ministers in the Cabinet were taking.

African teachers, headmasters and parents expressed outrage. Pass rates were already desperately low; this would force them down even further.

At more or less the same time the Transkei was due for independence, and it became clear that under the new legislation as many as 1.3 million urban Xhosa, whether born in the Transkei or not, would lose their South African citizenship and thus be liable for deportation.

The frustration and anger of Soweto’s residents now became intense. It was directed squarely at “stooge” homeland leaders like Kaiser Matanzima of the soon-to-be-independent Transkei.

Desmond Tutu, then Anglican Dean Johannesburg, publicly expressed the feelings of despair of Sowetans:

“Do you want to make us really desperate? Desperate people will be compelled to use desperate means. I am frightened ”¦ that we may soon reach the point of no return, when events will generate a momentum of their own and nothing will stop them reaching a bloody denouement.”

Predictably, Tutu’s appeal was ignored.

Source: a statement carried on the front page of the Rand Daily Mail on 1 May 1976.

Sifiso Ndlovu, in his book, The Soweto Uprisings: Counter Memories of June 1976, questions the role of SASM or any other organisation outside of Soweto in the evolution of the youth rebellion that followed. He stresses that the introduction of Afrikaans as a medium of instruction only affected Forms 1 and 2 (Grades 8 and 9), while SASM concentrated on senior students.

According to Ndlovu, the student leaders that later emerged ”” such as Tsietsie Mashinini and Murphy Morobe, both belonging to SASM ”” were students in the higher grades “and were not involved in our struggle”. That struggle began with a boycott of classes in protest against Afrikaans as a medium of instruction, which began in junior secondary and higher primary schools. As examinations approached in mid-year, students and parents became increasingly desperate about the situation. It seems that at this point SASM saw the opportunity to take a leadership role.

Several members of its national executive called a meeting at Soweto’s YMCA, which was intended to form a SASM regional branch. A large number of students attended. Tsietsie Mashini, a final-year student at Morris Isaacson High School in Jabavu, Soweto, won approval for a mass demonstration on 16 June. Tebogo Mohapi recalls that students thought they would have a peaceful demonstration ”” a surprise for their teachers and the authorities, but peaceful.

Surprise it was, but peaceful it was not. Police violence against the student protestors, as we know now, provided the spark which ignited all the frustrations and grievances that had been building up over the previous ten years. After 16 and 17 June 1976, nothing in South Africa would be the same again. An old era was past. A new one was beginning.