From the book: Le Rona Re Batho (An account of the 1982 Maseru Massacre) by Phyllis Naidoo, South Africa, 1992

By December 1982, the government of Lesotho under the leadership of Dr. Leabua Jonathan had changed its stance toward South Africa.

Prime minister - leabua Jonathan

Prime minister - leabua Jonathan

Chief Jonathan was one of the first Black African leaders to sup with Vorster, South Africa's then Prime Minister. Vorster first shook a black hand when the Malawian delegation arrived in South Africa.

A clasped black and white hand was featured in most front pages of our dailies applauding this earth-shattering event.

With Lesotho's independence in 1966, SA was prostrate in her support for the new Black government of Lesotho. Even Lesotho's new Chief Justice came from SA together with 4 magistrates and a host of South African personnel. However, with time this relationship waned and White South African personnel were withdrawn.

In 1952, the BCP (Basutoland Congress Party) was formed in Lesotho. In 1958 it split into the BNP (Basutoland National Party) and BCP. The BNP won the first election and Lesotho was born. The second elections in 1970 ended in the declaraÂtion of a State of Emergency and the abolition of the constituÂtion. The BNP usurping power continued at the helm, after a BCP victory at the polls.

Political killings and imprisonment followed, as well as mass repression, and a period of great unrest.

In 1973 the Lesotho Government, in an offer of reconciliation nominated 20 BCP representatives. Sixteen accept the invitation and were promptly excluded BCP. G. Ramoreboli, a top BCP member was appointed Minister of Justice. In 1974, following political unrest and violence in Lesotho, the BCP leadership went into exile. When Zambia and Botswana declared Ntsu Mokhehle and undesirable persons, the BCP sought assistance from South Africa. The Lesotho Liberation Army (LLA) was formed with South Africa's backing.

Since South Africa's mining revolution at the end of the last century, Lesotho has become increasingly dependent on its migrant labour. About 140,000 worked in South Africa as miners. Their limited income is vital to Lesotho's economy. Three quarters of Lesotho's state revenue emanates from the customs union with SA.

Having this stranglehold on Lesotho's economy, South Africa sought to have Lesotho's support for its homeland policy, namely ethnic and tribal political rights of the majority of the people in 13% of South Africa's land. The international community overtly refused to recognise the homelands policy and when Lesotho followed suit. South Africa's patience was at breaking point.

After the murder and mayhem following the Soweto uprising in June 1976, Lesotho became openly critical of South Africa. Its refusal to recognise Transkei further distance Lesotho from South Africa.

South Africa in turn, smarting from this changed stance of Chief Jonathan, gave asylum to the BCP and openly assisted the LLA. To retain this support the LLA became openly critical of the ANC. Its leaflets dropped after acts of violence in Lesotho always targeted the ANC. The ANC was never the enemy of the BCP.

Two further attempted coups against the Lesotho government, striking Basotho miners killed in South Africa, South African refugee kidnapped by South Africa, and South Africa's refusal to set up industries in Lesotho, were so many pressures exerted on Lesotho by the South regime.

Lesotho rejected P.W. Botha's proposal of a 'constellation of Southern African states (CONSAS). Instead Lesotho embraced SADCC - Southern African Development Coordination Conference, (Lesotho in fact was one of its founder member),

In 1979 a parcel bomb sent with Sechaba, the official organ of the ANC, injured 6 ANC members in Maseru. The Lesotho Post Office in Maseru was the next target. Several BNP members were killed. It was these atrocities that resulted in Chief Jonathan agreeing to talk with South Africa's President P.W. Botha.

They met at Peka Bridge border post on 20 August 1980. Following this meeting there was a lull in LLA activity. HowÂever this lull in cross border violations was short lived. By 1981, destabilisation activities commenced. Shops, fuel depots, elecÂtricity installations etc were targets.

In December 1980 and April 1981 Lesotho refused to hand over fleeing ANC guerillas.

Pik Botha in a meeting with Lesotho's Foreign Minister Mooki Molapo, in Cape Town on 19 August 1981 said,

"THERE WOULD BE NO LLA, IF YOU REMOVED ALL REFUGEES FROM LESOTHO. IF YOU WANT US TO DO SOMETHING ABOUT LLA CAMPS YOU MUST DO SOMETHING ABOUT THE ANC"

There was no doubt that the LLA had official South African support. Lesotho was offered Ntsu Mokhehle, BCP's head of LLA, in exchange for Chris Hani of the ANC. Lesotho refused proudly, saying if my memory serves me at all, that they Lesotho were not in the meat trade.

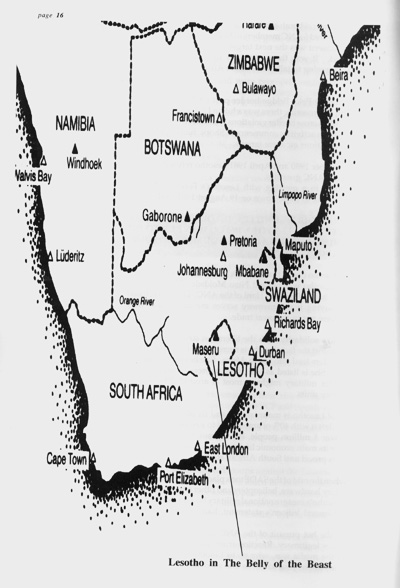

Lesotho's solidarity with the liberation struggle has to be viewed against the fact that she is surrounded by South Africa. Her 12 borders lead into South Africa. She lies in the 'belly of the beast'. She is listed as one of the poorest countries in the world. Her military might at most is around 2000 PMU -paramilitary units.

Most of Lesotho is mountainous and its painful, historical carve up, left it with 40% of arable land to sustain a population of just over 1 million people. Its migrant workers to South Africa are its main economic lifeline. It had very little scope to sustain its proud anti South African stance.

So when the raid of the SADF took place on 9 December 1982, the military hardware, helicopters and other support outnumÂbered Lesotho's meagre national military budget. South Africa, despite General Viljoen's statement, had to teach Lesotho a lesson.

With the hot pursuit of the ANC they attempted to give themselves legitimacy. Reaction from many people in South African the media was, why go to Lesotho to find the ANC when they are in your kitchens and gardens.