A self-taught, award winning artist and photographer. Badsha played an active role in the South African liberation struggle, as a cultural and political activist and trade union leader.

Born in Durban, Natal (now KwaZulu-Natal – KZN) on 27 June 1945, Omar Badsha grew up in a working-class Gujarati Indian Muslim family. His grandparents immigrated to South Africa from India in the first decade of the 20th century.

His father, Ebrahim Badsha, was a shop assistant, sign writer, graphic designer and founding member of the Bantu, Indian and Coloured Arts Group (BICA), the first black arts group in Durban. Ebrahim was a major influence on his son’s interests in the arts, photography and political activism. His uncle, Moosa Badsha, was a freelance photojournalist who worked for several local Durban-based newspapers and publications.

Badsha became politically active as a high school student in the wake of the 1960 Sharpeville Massacre and the Apartheid government’s subsequent banning of the liberation organisations. He joined the Durban Students’ Union and became its deputy secretary. In the mid-1960s, he was drawn into the African National Congress (ANC) underground and worked with Phyllis Naidoo, AKM Docrat, Archie Gumede and others.

In 1965, the South African government denied him a passport to travel abroad to study art. Later, that same year, he entered a small woodcut in the Arts South Africa Today exhibition, which won him the Sir Basil Schonland Prize. The winning of a major award was the beginning of Badsha’s lifetime work as an artist, a photographer and an influential voice in anti-apartheid artists’ and writers’ circles.

Badsha was among the few Black artists who worked outside the mainstream white-dominated commercial gallery circuit. He refused to exhibit in segregated venues or state-sponsored international shows. During the mid-sixties, he met and developed close friendships with the artist Dumile Feni, and writers like Mafika Pascal Gwala, Mandla Langa and other leading artists, many of whom were prominent in the Black Consciousness Movement (BCM).

In 1970, Badsha played a leading role in the revival of the Natal Indian Congress (NIC). He worked alongside Rick Turner, Ela Gandhi, Mewa Ramgobin and other activists to run work camps at the Phoenix Settlement and to form the short-lived Education Reform Association. In the wake of the 1973 Durban strikes, Badsha stopped exhibiting. He began to work closely with trade unionists Harriet Bolton, David Hemson, Halton Cheadle and students from the National Union of South African Students (NUSAS) Wages Commission.

He recruited Harold Nxasana, Alpheus Mthethwa, Doris Skosana and other members of the ANC underground in Durban to work in the General Factory Workers Benefit Fund (GFWBF) as well as into the Institute of Industrial Education (IIE).

In 1973, he moved to Pietermaritzburg to help with a strike at a textile factory and to run the Trade Union Advisory Coordinating Council (TUACC) office there. With the banning, in 1974, of his colleagues, David Hemson, Halton Cheadle and others, Badsha moved back to Durban. Here, he was responsible for establishing the Chemical Workers Industrial Union (CWIU). He served as the CWIU’s first general secretary.

Badsha's passion for photography developed through his desire to document work-related injuries in chemical plants and serve as a resource for trade union educational initiatives. He left the trade unions in 1976 and started working full-time as a photographer.

He was approached by the banned academics and political activists Professor Fatima Meer to work on a book of photographs on children under apartheid. The book Letter to Farzanah was published in 1987 and immediately banned. The banning of the book received international condemnation and had the opposite effect of what the state had intended.

Badsha was approached by the former political prisoner Shadrack Maphumulo (also banned) to assist in mobilising people to fight against removals and to build community civic organisations in the Inanda area, north of Durban.

Badsha’s darkroom became the hub and training ground for young would-be photographers, which eventually led to the formation of Afrapix, the legendary South African photographers collective. Afrapix played a leading role in documenting the popular struggles of the 1980s and the popularising of a social documentary photography movement in the 1980s.

Badsha became well known for curating several ground-breaking photographic books and exhibitions—Letter to Farzanah which was banned by the government, Imperial Ghetto, a seminal photographic book on Durban’s inner city Indian community, Imijondolo, his book on the struggle against mass removal in Inanda and South Africa: The Cordoned Heart the exhibition and book which was part of the Carnegie Commission into Poverty in South Africa.

In 1982, Badsha was appointed head of the photography unit of the Second Carnegie Commission on Poverty and Development. He recruited 20 photographers to participate in the project and curated the highly influential exhibition and book South Africa: The Cordoned Heart. The exhibition and book were critically acclaimed internationally as a seminal work that created a new vocabulary to tell the South African story. Despite a great deal of international pressure, the South African government refused him a passport to travel to the opening at the International Centre of Photography (ICP) exhibition in New York, United States of America.

The success of the Carnegie project led to the establishment of the Centre for Documentary Photography at the University of Cape Town in 1987.

Badsha and his family moved to Cape Town, where he became active in the United Democratic Front (UDF) and was instrumental in the founding of the Cultural Workers Congress (CWC).

In 1990, after much lobbying by American institutions, for the first time in 25 years, Badsha was issued a passport, which was valid for a mere three months. He travelled to London and was assigned by the ANC leadership to undertake a speaking tour of America for the ANC. In New York, he met his old friend Dumile Feni and visited Ernest Cole, the legendary exiled South African photographer in hospital and was with him a day before his death.

After the unbanning of the ANC in 1990, Badsha became the head of the organisation’s Western Cape Arts and Cultural Department. He spearheaded the creation of the Federation of South African Cultural Organisations (FOSACO) and worked fulltime as a volunteer as well as serving on the political committee of the ANC’s Western Cape 1994 election campaign.

Unlike many other activists he did not make himself available for political office in the new government but rather continued to work with civil society and grassroots youth and cultural organisations. In 1985, he establishing the Ikapa Arts Trusts, which organised the annual Cape Town Art Festival.

In 1997, his wife, Nasima, was appointed head of the newly established division of Higher Education in the Department of Education, and the family moved to Pretoria.

Badsha received a grant from the Danish Government to document life in Denmark. The exhibition of this work was opened by then South African Vice President Thabo Mbeki and the Danish Foreign Minister. Badsha travelled to India in 1996 on a travel grant from the Indian Government. He undertook a photographic project on the small town of Tadkeshwar, the birthplace of his grandparents.

In 2000, Badsha established South African History Online (SAHO), a non-profit online history and heritage project, one of Africa’s largest history websites.

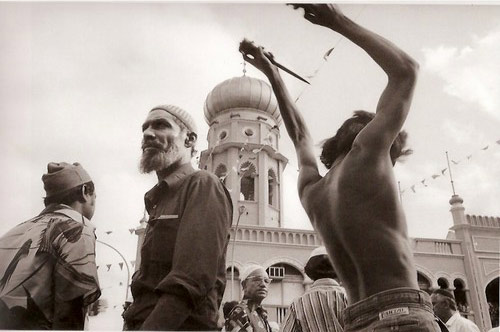

An image from Badsha's Imperial Ghetto exhibition

An image from Badsha's Imperial Ghetto exhibition

In 2001, he published Imperial Ghetto, a study of life in the Grey Street complex of Durban, and edited the book “With Our Own Hands” (2002), a book focused on the government's poverty relief programmes. In 2008 wife Nasima resigned from the Education Department and the family moved back to Cape Town.

In 2015, his retrospective exhibition titled Seedtime opened at the Iziko National Museum in Cape Town. In December 2017, he was awarded an Honorary Doctorate from the University of Stellenbosch and an honorary doctorate from the University of Fort Hare in 2025.

In April 2018, President Cyril Ramaphosa awarded him the National Order of Ikhamanga (silver).

Omar Badsha – Political Activist and Cultural Worker

View list of awards, publications and exhibitions.