Related Collections from the Archive

Related content

In April 1982 Joe Foster, the General Secretary of the Federation of South African Trade Unions (Fosatu), gave the keynote address at the second Fosatu national congress in Hammanskraal.

Fosatu, with roots in the Durban strikes of 1973, was formed in 1979 and aimed to build democratically organised, worker-controlled and militant industrial unions. The speech given by Foster, and adopted as Fosatu policy, was a direct challenge to the claims of the ANC and SACP to represent the nation as a whole, and is now often seen as a prescient warning about the future to come.

This is an edited excerpt from The Workers’ Struggle: Where does Fosatu Stand? (1982), an address given by then Fosatu General Secretary Joe Foster.

Three years ago – almost to the day – we met in this very same place to form Fosatu (the Federation of South African Trade Unions). Today, we have set our theme – the workers’ struggle – in a serious attempt to further clarify where we as representatives see Fosatu standing in this great struggle. That we are discussing this theme today and resolutions that relate to it is a justification of our original decision to form Fosatu and shows how seriously we take the new challenges that face us three years after that decision. Clearly, any such discussion raises many very important issues and the purpose of this paper is to try to bring together these issues in ways that will help guide our discussions.

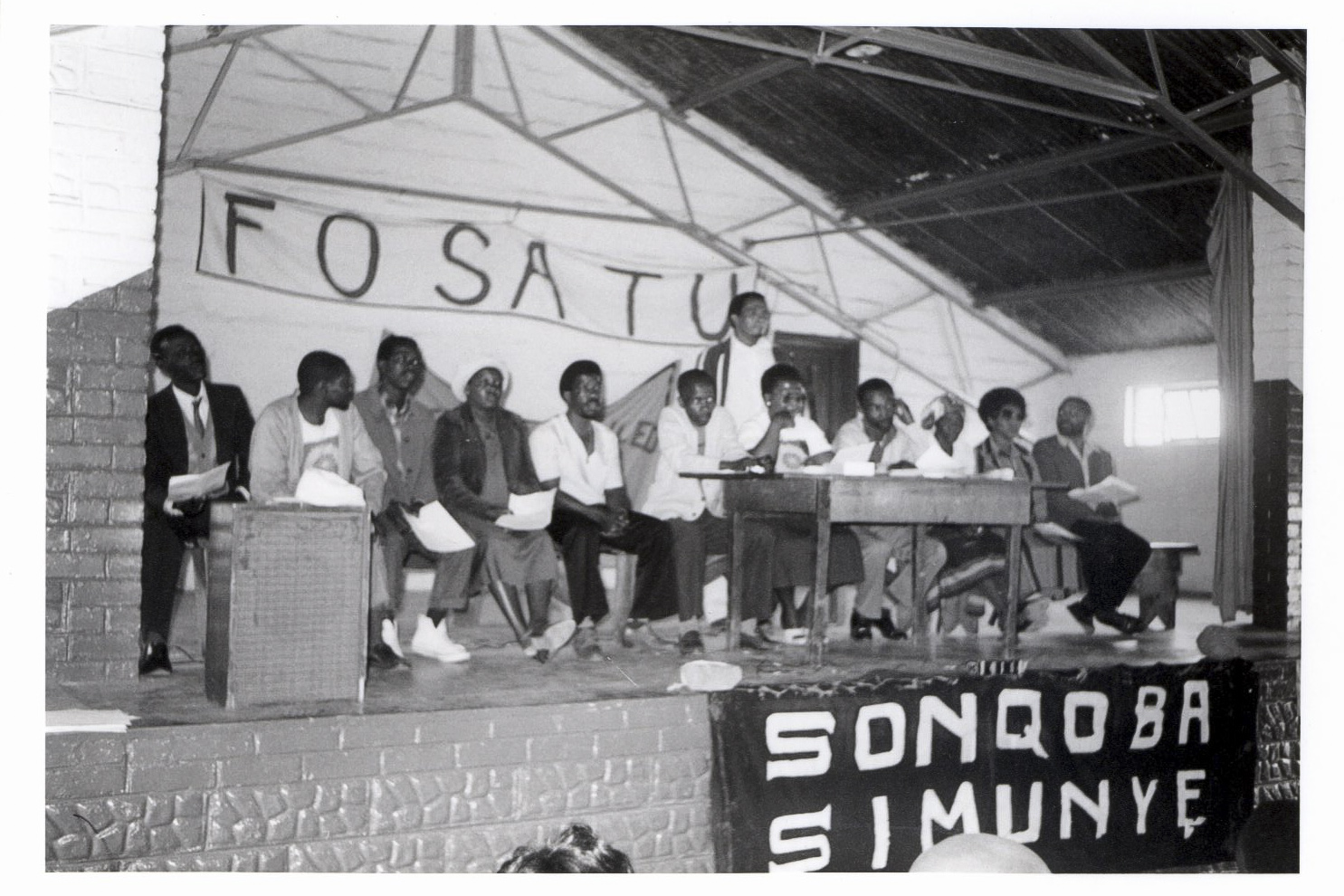

Circa 1980s: A banner proclaiming ‘sonqoba simunye’, we will win as one, adorns the stage of a meeting at which Fosatu made a concerted call for unity. (Photograph courtesy of Wits Historical Papers) Image Source

Need for a working-class movement

The growing size of the economy and the dramatic changes taking place in capital have created important new conditions in the economy. We also have to take into account the speed and manner in which the economy has developed. In discussing the working-class movements in the advanced industrial economies, we have to bear in mind that in most cases they took about 100 years or more to fully develop. Industry started first by building larger and larger factories, and bringing people together in these factories.

The new capitalist had to struggle politically with the older ruling classes over labour, land, taxation policy, tariff protection, political rights and political power. The mechanisation became more important and there was a definite change in production processes. As this happened, the skilled workers who had usually given leadership to the craft unions found themselves in a very difficult position. As a result, leadership problems in the organisation of trade unions and the political environment developed in a complex and relatively slow way.

In South Africa, this has been condensed into 60 or 70 years and, from the outset, large-scale capitalist enterprises dominated. The birth of capitalism here was brutal and quick. The industrial proletariat was ripped from its land in the space of a few decades. At present, capitalist production massively dominates all other production. There are no great landlords on their agricultural estates, and there is no significant peasantry or collective agriculture. Virtually everyone depends for all or part of their income on industry or capitalist agriculture.

The working class has experienced a birth of fire in South Africa, and they constitute the major objective political force opposed to the state and capital. There is no significant petty bourgeoisie or landed class that will assist in the organisation of workers.

The great concentration of capital has also meant a greater concentration of workers. These workers generally have a higher level of basic education and skills than before, and their links with the past are all but broken so that more and more a worker identity is emerging. This is reinforced by the sophisticated strategies that are designed to “deracialise” industry and some other areas of society.

The privilege pile

The effect of this is to divide off certain privileged members of black society, leaving workers at the bottom of the privilege pile. The concentration of workers in industry has also concentrated them in great urban townships. The particular structure of the South African economy with its high degree of state involvement, price controls and heavy dependence on international markets has made it a very sensitive economy. As a consequence, attempts to “buy off” the major part of the working class will fail. It is more likely that as some readjustments of privilege are attempted that it will have to be workers that suffer through inflation and the lack of basic commodities.

The above factors and South Africa’s international economic importance are likely to force capital into the political open and as a consequence develop a worker response. Although capital can at present hide behind apartheid, it is also the case that if workers organise widely enough, they can get great support from the international labour movement. Also, international public opinion has to be carefully watched by capital because both international and South African capital are dependent on their links with the rest of the world.

These, then, are some of the important factors that are favourable to the development of a working-class movement in South Africa. However, this does not mean that this will automatically happen. To understand this, we need to look at the present political environment more carefully to see both the present political tendencies and to establish why some active leadership role should be played by the unions and Fosatu in particular.

Workers need their own organisation to counter the growing power of capital and to further protect their own interests in the wider society. However, it is only workers who can build this organisation, and in doing this, they have to be clear on what they are doing.

As the numbers and importance of workers grows, then all political movements have to try and win the loyalty of workers because they are such an important part of society. However, in relation to the particular requirements of worker organisation, mass parties and popular political organisations have definite limitations, which have to be clearly understood by us.

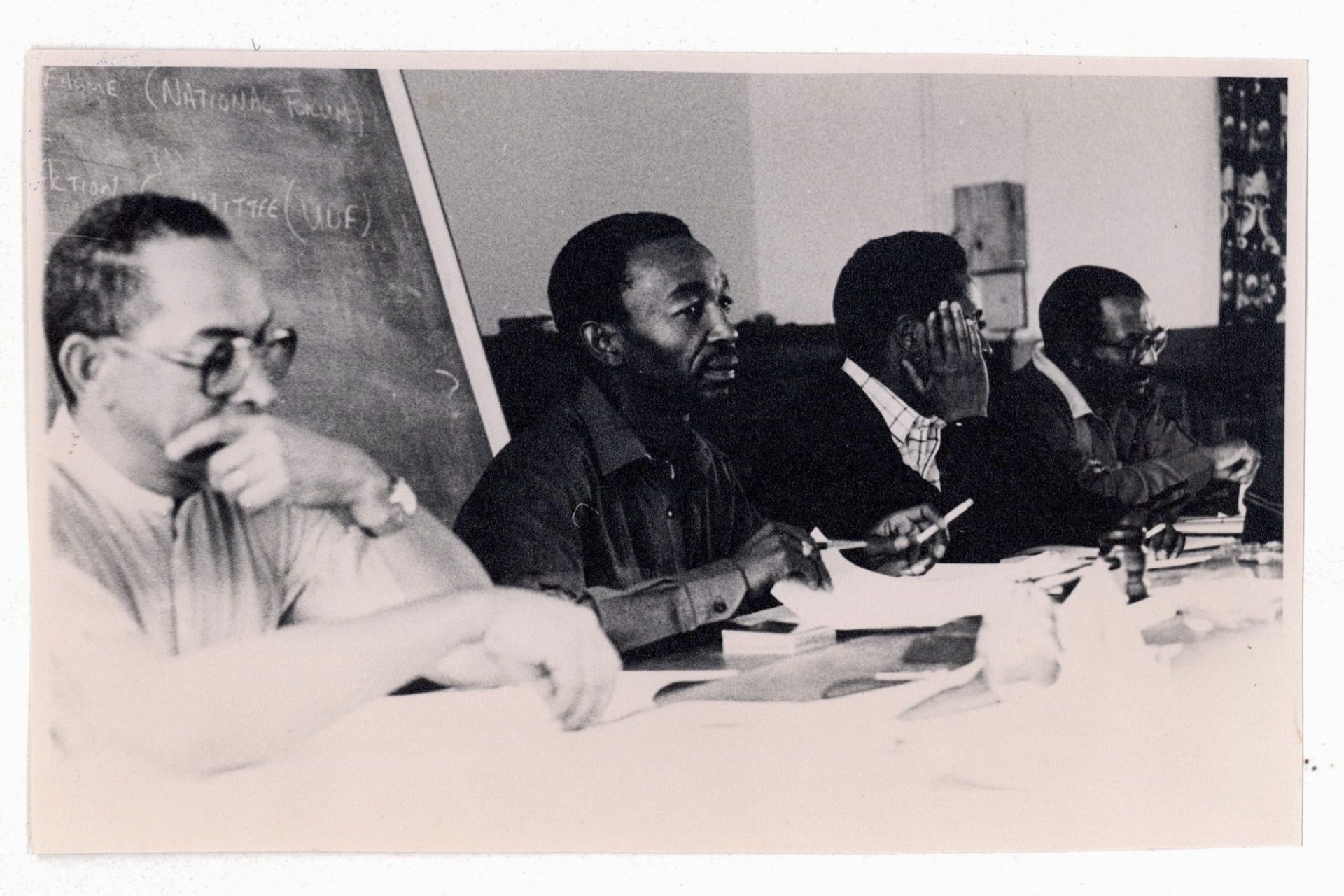

Circa 1980s: From left, Joe Foster, Chris Dlamini, John Gomomo and an unidentified fourth man at a Fosatu meeting. (Photograph courtesy of Wits Historical Papers)Image Source

International presence

We should distinguish between the international position and internal political activity. Internationally, it is clear that the ANC is the major force with sufficient presence and stature to be a serious challenge to the South African state and to secure the international condemnation of the present regime. To carry out this struggle is a difficult task because South Africa has many friends who are anxious to ensure that they can continue to benefit from her wealth. The fact that the ANC is also widely accepted internally also strengthens its credibility internationally.

However, this international presence of the ANC, which is essential to a popular challenge to the present regime, places certain strategic limitations on the ANC, namely: to reinforce its international position it has to claim credit for all forms of resistance, no matter what the political nature of such resistance. There is, therefore, a tendency to encourage undirected opportunistic political activity. It has to locate itself between the major international interests. To the major Western powers, it has to appear as anti-racist but not as anti-capitalist. For the socialist East, it has to be at least neutral in the superpower struggle and certainly it could not appear to offer a serious socialist alternative to that of those countries as the response to solidarity illustrates.

These factors seriously affect its relationship to workers. Accordingly, the ANC retains its tradition of the 1950s and 1960s when, because there was no serious alternative political path, it rose to be a great populist liberation movement. To retain its important international position, it has to retain its political position as a popular mass movement. This clearly has implications for its important military activities.

Internally, we also have to carefully examine what is happening politically. As a result of the state’s complete inability to effect reform and the collapse of their Bantustan policy, they are again resorting to open repression. Since 1976, in particular, this has given new life to popular resistance and once again the drive for unity against a repressive state has reaffirmed the political tradition of populism in South Africa. Various political and economic interests gather together in the popular front in the tradition of the ANC and the Congress Alliance.

Worker organisation

In the present context, all political activity, provided it is anti-state, is of equal status. In the overall resistance to the regime, this is not necessarily incorrect. In fact, without such unity and widespread resistance, it would not be possible by means of popular mass movements to seriously challenge the legitimacy of the present regime.

However, the really essential question is how worker organisation relates to this wider political struggle. I have argued above that the objective political and economic conditions facing workers is now markedly different from that of 20 years ago. Yet there does not seem to be clarity on this within the present union movement. There are good reasons for this lack of clarity.

As a result of repression, most worker leadership is relatively inexperienced, and this is made worse by the fact that their unions are weak and unstable organisationally. The union struggles fought against capital have mostly been against isolated companies, so that the wider struggles against capital at an industry or national level have not been experienced.

This also means that workers and their leadership have not experienced the strength of large-scale worker organisation nor the amount of effort required to build and democratise such large-scale organisations. Again, state repression and the wider political activity reinforce previous experience where the major function of workers was to reinforce and contribute to the popular struggle.

Politically, therefore, most unions and their leadership lack confidence as a worker leadership. They see their role as part of a wider struggle but are unclear on what is required for the worker struggle. Generally, the question of building an effective worker organisation is not dealt with and political energy is spent in establishing unity across a wide front.

Focus on workers

However, such a position is a great strategic error that will weaken if not destroy worker organisation both now and in the future. All the great and successful popular movements have had as their aim the overthrow of oppressive – most often colonial – regimes. But these movements cannot and have not in themselves been able to deal with the particular and fundamental problems of workers. Their task is to remove regimes that are regarded as illegitimate and unacceptable by the majority.

It is, therefore, essential that workers must strive to build their own powerful and effective organisation even while they are part of the wider popular struggle. This organisation is necessary to protect and further worker interests and to ensure that the popular movement is not hijacked by elements who will in the end have no option but to turn against their worker supporters.

Broad and complicated matters have been covered, and it is difficult to summarise them even further. However, I shall attempt to do so in order for us to try and examine the role that Fosatu can play in this struggle.

That worker resistance such as strike action helps build worker organisation but by itself it does not mean that there is a working-class movement. There has not been and is not a working-class movement in South Africa. The dominant political tradition in South Africa is that of the popular struggle against an oppressive, racist minority regime.

That this tradition is reasserting itself in the present upsurge of political activity. However, the nature of economic development in South Africa has brutally and rapidly created a large industrial proletariat.

That the size and development of this working class is only matched by its mirror image, which is the dramatic growth and transformation of industrial capital. Before it is too late, workers must strive to form their own powerful and effective organisation within the wider popular struggle.

This article was first published by New Frame.