Related Collections from the Archive

There have always been general assumptions that the KhoeSan people (‘Khoe’ is the correct spelling) are extinct and that their languages at the Cape died out with them. Another assumption is that they once spoke ‘Cape Khoe’ but that this language has also died out because it was last heard used in public in the Cape by Uithaalder in his protest against the introduction of a new vagrancy law against the KhoeSan in 1834 (Ross 2017).

Du Plessis’ comprehensively scholarly work was made possible with essential collaboration with trusted people from the community such as KhoeSan activist and researcher Edward Charles Human; well-known experts University of Namibia linguist Dr Levi Namaseb and colleague Dr Niklaas Fredericks; and language activist and now University of Cape Town inaugural Khoekhoegowab Foundation course teacher, Bradley Van Sitters (presently the /Xarra forum Language Commission chair, Centre for African Studies, UCT).

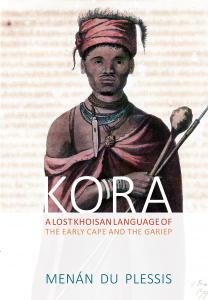

Menán du Plessis is a linguist who credits their work in the introduction, referring to ‘the authorial “we”’. This epistemological point should not be underscored in our times as du Plessis notes that ‘the idea for the project emerged out of many long and animated conversations in Bloemfontein and the initial work in the field was carried out by a team of us, so that when it came to writing everything up, it was natural to adopt the point of view of the original collective…the final work reflects a consensus…’ It is thanks to this collaboration, that this contribution could be made to fill the gaps in precolonial knowledge of the KhoeSan people which is immensely invaluable. Considered a ‘previously lost’ Kora language of the early Cape and Gariep, the compiled archive is available in word and sound (a printed book and South African History Online platform).

du Plessis was alerted to the existence of the last speakers in 2007 by Dutch historian Mike Besten. Besten encountered in his research that two or three elderly people in and around Bloemfontein and Bloemhof still remembered fragments of the old language of the Korana people (referred to by its speakers as !Ora). This was a remarkable encounter in historiography as it was believed that there were no such speakers left of a language considered ‘closest to the language spoken by the original Khoi inhabitants of Table Bay when European sailing ships began to appear around the Cape coastline towards the end of the 15th century’. These speakers recorded are Oupa Dawid Cooper and Ouma Jacoba Maclear of Bloemhof. ‘On the verge of her 100th birthday, she proved to be the most fluent and reliable of the surviving speakers, with a well-preserved vocabulary and syntax.’

Kora is dense and uncompromisingly technical; a linguistic treasure with maps, tables and a huge number of figures. The work draws on Nienaber’s work on Cape Khoekhoe and a variety of sources. The first two chapters make easy reading as they are historically and sociologically contextual, followed by technical chapters on the sounds of Kora and the language’s structures. A very interesting and substantive chapter is the one on heritage texts of the Kora people which spans over 100 pages. For those who want to learn Kora, they’ll be curious to read the Kora-English dictionary with its English-Kora index. KhoeSan activists would also find an interest in the special list of Korana clans; names for animals, birds and smaller creatures; plants, and plant products. Of the over 7000 languages spoken in the world, over 2,500 are in danger. In this year (2019) of the United Nations’ Year of World Indigenous Languages, this work deserves therefore major attention and should be read by scholars and the public in general and preserved through language teaching and education in southern Africa.