This article was written by Meghan Knapp and forms part of the SAHO and Southern Methodist University partnership project

Abstract

The African National Congress was created in 1912 and a year later the Bantu Women’s league was created. In 1944, women were granted membership for the ANC. The ANCWL fought against racial and gender discrimination, alongside the ANC, until its unbanning in 1960. For 30 years they fought against apartheid through underground organisations. In 1990 the government unbanned the league. Since then, the league has been very active in the current day South African government and focuses on improving women’s issues within the country as well as increasing women’s participation in government.

Key Terms

African National Congress Women’s League, Winnie Mandela, Quota System

The ANC Women’s League in the Struggle for Women’s Rights in South Africa

Over the past century South Africa has been a country of extreme internal turmoil and conflict. Many organisations within the country have helped to shape the way that South African history has unfolded. One of these many organisations is the African National Congress Women’s League. The ANC Women’s League played a distinctive role in the furthering of equality within South Africa. From its creation in 1918 as the Bantu Women’s League up until the ANC’s banning in 1960, the league was very active, participating in riots and resistance against an apartheid government. During this period, the ANCWL experienced a series of ups and downs that affected what it had sought to accomplish. After the unbanning of the ANC in 1990, the ANC Women’s League struggled tremendously to re-establish a concrete organisational structure and leadership but over time it has transformed into a political entity that works to further women’s participation within the government in South Africa.

The ANC Women’s League has had a long and chaotic history in South Africa. In 1912, the African National Congress was created after White settlers established a government that lacked rights for Black South Africans. Initially women were not allowed to be members of the ANC and thus had no voting rights in the organisation. Regardless, the Bantu Women’s League was formed in 1913. The league worked at ‘uniting African women against pass laws, rising food prices’ and forms of discrimination at this time (Myakayaka-Manzini 1). In 1944, the ANC decided to allow women to be members of the organisation and consequently in 1948 the African National Congress Women’s League was officially started. Mavivi Myakayaka-Manzini, who was the leader of the ANCWL in Johannesburg for two years and later elected as an ANC member of parliament, wrote that, ‘from its founding, the League had a vision to unite South African women across the colour barrier’ (Myakayaka-Manzini 1). In the 1950s, the league was extremely active in resistance, which can be seen in many different occurrences. A few examples include the beer hall riots in 1959 and, with the help of the Federation of South African Women, the creation of Women’s Charter in 1954 as well as the mass demonstrations for the anti-pass campaign in 1956. In 1960, the ANC was banned and thus so was the ANCWL but resistance still continued and members of the league became involved in underground movements and organisations such as Umkhonto we Sizwe. In 1990, the ANC was unbanned and the women’s league worked to form a strong and organisationally sound group that would help to improve gender equality and address women’s issues in the country. The league does not always have success but is very active today and is making great progress for women’s rights in South Africa.

The women’s league first struggled to establish a functional organisational structure after its unbanning and thus had initial problems with furthering their agenda. After thirty years of inactivity, the organisation had much to redevelop and re-establish in order to bring it to a fully functioning part of the current government. Initially, the league elected a group of ten women, led by Gertrude Shope and Alberta Sisulu, to help to set up and organise the group (SPEAK 5). In an article in the magazine SPEAK that was published directly after the unbanning of the league and the return of exiled women, the author claims that the needs of the league included the ‘need to recruit more women into the ANC”¦’ and the ‘need to build confidence”¦’ (SPEAK 6-7). However, in a book titled Women's Organizations and Democracy in South Africaby political scientist Shireen Hassim, Hassim claims that after the unbanning, ‘Media interviews with Shope reveal the extent to which the role of the league was unresolved even at the leadership level’ (Hassim 123). This exhibits that in the beginning, even the leaders had problems establishing the league’s goals and what it was attempting to do for the women of after the end of apartheid. This unclear role caused the league to not be taken seriously by the public and was often criticised as being merely a ‘mothers club’ (Hassim 123). In 1991, the league met at its Kimberly conference to debate these issues of structure. Hassim discusses the main issues that were talked about involving the structure of the league such as the power of specific branches and leader accountability. She says, ‘The problem with taking these commitments further was that the league had yet to establish itself as an organization with members and mandates’ and also that ‘the pace of the events internal to the league and in the negotiation process would making building organization even more difficult than the leadership anticipated’ (Hassim 124). This reveals that in the beginning the league had many problems just keeping up with the speed that change was happening in the ANC as well as in the country. Overall, in the early years after their unbanning the league struggled to establish a concrete organisational structure that could function well with the changing government of South Africa.

During the few years after the unbanning, ANC Women’s League leaders caused controversy and issues for the league. After years of no direct activity from the league itself in South Africa, people were concerned about many of the women in the league and their ability to do a good job. In an issue of SPEAK magazine, an organiser of the women’s league, Khosi Xaba, talks about how many members of the league had just returned from exile and thus the public was concerned that they were out of touch with the situation (Meer 125). Another aspect of the leadership that held concern was that many members of the league were married to male members of the ANC. Hassim suggests that because of this, ‘many feminists were concerned that the league would simply become another ‘wives’ club’”¦’ (Hassim 124). This comment suggested that people were concerned with the validity and affectability of the league. One of these wives was Winnie Mandela who, in 1991, ran against Gertrude Shope for president. Mandela ended up losing to Shope but was still given a seat on the league’s executive committee as well as being appointed to chief of social welfare for the African National Congress. Winnie had been extremely active in the movement for liberation but her ideals were often questionable in the eyes of the public. In one speech in 1986 Winnie said, ‘Together hand-in-hand, with our boxes of matches and our necklaces, we shall liberate this country’ (Winnie 1). In this she was referring to a type of killing at the time where the victim would have a tire around their neck and be set aflame. Soon after her being appointed in the ANC, Winnie was ‘charged with the kidnapping and murder of 14 year old Stompie Seipei. Stompie was believed to be a police informant against the struggle’ (Winnie 1). Due to the controversy that surrounded Winnie, an article published in 1991 in the New York Times suggested that her ‘flamboyance and outspoken militancy, which made her popular with younger members, proved a liability with a majority of delegates at the conference’ (Wren 1).Overall, the league believed that Winnie’s militancy and actions proved to be too much controversy and that her leadership would have potentially hurt the organisation. However, Winnie was elected in 1993 as president of the ANC Women’s League and held the position for 10 years. Throughout these years Winnie was charged with fraud and theft, which caused the league to have a lot of negative attention surrounding them. Altogether, there were multiple issues with the leadership of the women’s league in the early years after its unbanning.

After having so many issues with organisation and leadership, the league worked to establish a concrete and well-rounded organisational system that would allow them to functionally invoke change. The league worked to develop a constitution that would establish a concrete set of goals, structure, and various aspects of the organisation. Over time the league has met at National Conferences to discuss and amend changes to this constitution. The latest constitution was adopted at the 5th National Conference in 2008 and is in use today (ANCWL Constitution 1). This method of amending the constitution every five years proves to be very forward thinking. The league is able to see how the country changes over time and then adjusts to better fit that change. The constitution itself is organised by rules, which have the job of explaining anything from the objectives of the organisation to the jobs of committees to rules of elections. Right off the bat it states, ‘women shall participate in all political structures of the ANC, in leadership structures and all programs designed for the socio-economic development of the country’ (ANCWL Constitution 1). After previous confusions of identity for the ANCWL, this statement clearly and strongly claims what will happen for women in the South African government. Further, the second rule states the aims and objectives of the league, which helps even more to establish a clear identity at the start and it can build off of that. Another rule of the constitution is titled ‘Organisational structure of the ANC WL’and explains that,‘ANCWL structures shall be divided into the provinces whose areas and boundaries shall coincide with provinces of the ANC’ (ANCWL Constitution 1). This was an extremely important aspect to develop because the league had many issues organising initially. They set it up so that it would coincide with what the ANC had developed with respect to their involvement in provinces and this would help the league to more effectively work successfully with the ANC. This rule also lists the major organs of the league, which they go into more detail later in the constitution. These include the various conferences that will elect certain committees that deal with issues on different levels. They divide the league into committees on a regional, provincial, and national level in order to successfully carry out policy and programmes as well as deal with issues hands on. This structure that the league developed is very strong and helps to make sure they are able to fully address issues by having access to all levels of location in South Africa. Although the league had a few missteps after its unbanning, it has developed a strong framework that has helped it to be often successful in South Africa.

With a firm structure in place, the women’s league has made great progress in increasing the amount of female participation in government. One of the main goals was to implement an affirmative action policy in order to ensure that women would be guaranteed a place in the South African government. In 1991, at the ANC National Conference, the league attempted to implement this affirmative action policy but failed. They desired at least 30% of seats on the National Executive Committee to be filled by women (Meer 125). After the failure at the conference, Baleka Kgotsisile, secretary general of the league at the time, showed that they would not give up. She contended in an issue of SPEAK: ‘We’ve got the future looking at us”¦We must plan workshops and we must put pressure on the national leadership to make sure that the new constitution ensures the emancipation of women. This is where the ANC Women’s League campaign for a charter of women’s rights comes in’ (Meer 128). After this, Mavivi Myakayaka-Manzini, a leader of the league, said that, ‘After the conference we approached our Women’s League and ANC structures to initiate debate on the representation of women and the quota system. We identified our strategic allies among the male members of the ANC, who could also articulate this issue’ (Myakayaka-Manzini 3). The league continued to campaign and push for this quota system and in the 1994 elections they had success. The ANC used the quota system to put women on lists for legislatures and thus one-third of the elected representatives to national and provincial legislatures were women (Myakayaka-Manzini 3). This was an astounding achievement for the league. This success has continued as seen in South Africa’s 2009 elections, where the quota increased to 50%. These positive results have clear visibility as Myakayaka-Manzini points out. ‘Out of 27 ministers, nine are women, and of the 14 deputy ministers, eight are women. In cabinet, women are not only awarded the usual women- related portfolios, but they are also involved in almost all areas ”¦ In the national parliament, of the four presiding officers, three are women. Women are also playing a greater role in the civil service, as directors-general, deputy directors-general and chief directors’ (Myakayaka-Manzini 3). This success within South Africa with the help of the women’s league inspired a global movement of how women are represented in government. In a recent publication by professor Amanda Gouws, she claims, ‘In the past two decades there has been a growing international trend for countries to accept party, legislative and constitutional quotas or reserved seats for women’ (Gouws 71). Due to the success of the league’s campaign, now other countries worldwide have shown steps towards more equality in government. Despite many setbacks after the unbanning of the league, it has done powerful work toward the participation and equality of women in government roles.

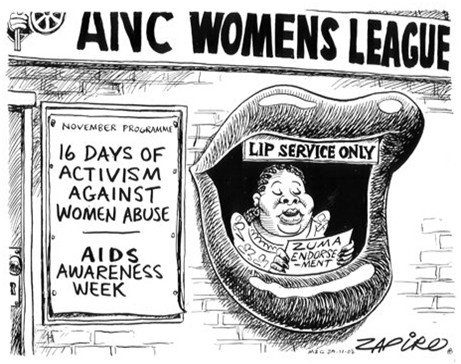

Even with the entirety of success for the ANC Women’s League, they still experience problems today. Despite the fact that the league built a seemingly strong organisational structure and achieved high numbers of women in government, it has been seen to falter over the past 20 years. In a recent article posted in Mail & Guardian titled ‘ANC Women’s League branches in shambles’, it informs that, ‘two of its provincial branches are in such a shambles that it will have to wait until April 2015 for its already delayed national conference to take place’ (Pillay 1). The article goes on later to say, ‘A membership audit has revealed that the league in the Western Cape and theEastern Cape does not have the required number of members’ (Pillay 1). The fact that they do not have enough women in good standing in those areas is very troubling for the league and shows how they do have certain problems today involving membership. Something else that the league has run into trouble with is their nomination and support of South Africa’s current president Jacob Zuma. In another recent article in Mail & Guardian, it criticises the league for defending Zuma after a sexist complaint. The article explains that Zuma was on trial in 2006 for rape and was later acquitted. However, the league still supported and endorsed him to run for president. The Women’s League received major criticism as their support ‘angered gender activists’ as well as many more individuals in South Africa (Pillay 1). In this cartoon

Artist: Jonathan Shapiro Source: Mail & Guardian Published: 2007 Accessed at: Image source

Artist: Jonathan Shapiro Source: Mail & Guardian Published: 2007 Accessed at: Image source

by political cartoonist Jonathan Shapiro, he criticises the women’s league for their endorsement of Jacob Zuma for president, suggesting that an endorsement for Zuma is at odds with AIDS awareness campaigns and programmes against domestic abuse. No system or organisation is flawless and there is always room for improvement as can be seen in the women’s league today. While they still continue to falter, the league still pushes for change for the women of South Africa and encourages them to participate in government.

The ANC Women’s League has been a vital organ for the furthering of women’s participation in government in South Africa. Although it struggled directly after its unbanning to get itself on its feet, it has become a political force that has pushed for and succeeded in more women’s equality and participation in government. They still continue to push for women’s participation in government, which can be seen today with the potential for a women presidential candidate in the upcoming elections (Pillay 1). The league also continues to work on other aspects of women’s issues such as ‘gender disparities in economic power-sharing’ and the need to ‘prioritise education’ (Montsheka 1). All in all, thimge league has overcome great challenges and has made tremendous progress for the women of South Africa in their push for rights and equality.