Women at the start of the 20th century

It is only over the last three or four decades that women's role in the history of South Africa has, belatedly, been given some recognition. Previously the history of women's political organization, their struggle for freedom from oppression, for community rights and, importantly, for gender equality, was largely ignored in history texts. Not only did most of these older books lean heavily towards white political development to the detriment of studies of the history and interaction of whites with other racial groups, but they also focused on the achievements of men (often on their military exploits or leadership ability) virtually leaving women out of South African history.

The reason for this ‘invisibility' of women, calls for some explanation. South African society (and this applies in varying degrees to all race groups) are conventionally patriarchal. In other words, it was the men who had authority in society; women were seen as subordinate to men. Women's role was primarily a domestic one; it included child rearing and seeing to the well-being, feeding and care of the family. They were not expected to concern themselves with matters outside the home – that was more properly the domain of men. Economic activity beyond the home (in order to help feed and clothe the family) was acceptable, but not considered ‘feminine'. However, with the rise of the industrial economy, the growth of towns and (certainly in the case of indigenous societies) the development of the migrant labour system, these prescriptions on the role of women, as we shall see, came to be overthrown.

This is a particularly appropriate time to be studying the role of women in the progress towards the new South African democracy. The year 2006 was a landmark year in which we celebrated the massive Women's March to the Union Buildings in Pretoria 50 years ago. Women throughout the country had put their names to petitions and thus indicated anger and frustration at having their freedom of movement restricted by the hated official passes. The bravery of these women (who risked official reprisals including arrest, detention and even bannings) is applauded here. So too are their organizational skills and their community-consciousness – they were tired of staying at home, powerless to make significant changes to a way of life that discriminated against them primarily because of their race, but also because of their class and their gender.

We invite you to read, in the pages that follow, on the important role played by women in twentieth-century South Africa. A list of works for further reading and some appropriate documents are also included in this archive. Women, half the population after all, have been silent for too long in our history books, and although this need is now to an extent being addressed, there is still a huge gap in our knowledge on the role of South African women. It is high time that our young South Africans should put the record straight.

By the beginning of the twentieth century in South Africa all the previously independent African polities had been conquered and put under white settler control. Furthermore the economic independence of these African societies had been destroyed and African men had been drawn into a labouring class on the mines (in the developing cities) and on white-owned farms. The discovery of minerals (diamonds in Kimberley in 1867 and gold on the Witwatersrand in 1886) had unleashed huge changes in the developing South African economy, and these were to become very significant for thee role played by women, particularly black women. Black men in the Cape Colony still had the vote (although a black man could not become a member of parliament), but elsewhere in South Africa black people (whether male or female) had no vote, nor were white women enfranchised.

The Anglo-Boer War of 1899-1902 (also called the South African War) had decimated the South African economy and left a deep divide in society, not only between black people and whites, but between Boer and British. Africans had aligned themselves with the British during this war, in the vain hope that after peace was signed they would be given a better deal. Instead the British had made some effort to reconcile with the Boers and ignored the claims of the Africans. A new white-controlled government was set up in 1901 and called the Union of South Africa.

What, then, was the position of women in South African society at the beginning of the 20th century? The answer is that black women in traditional African societies and similarly, white women in settler society, were subordinate to men. The position of women was inferior; the men took all the major decisions both in society at large and within the home. In other words South Africa was a patriarchal society.

Motherhood was women's primary role. They had to raise children, care for the home and see to the needs of the family. In African societies women were expected to undertake agricultural tasks as well to help feed the family. Others took in laundry to provide extra income while some entered the labour market as domestic servants. In settler society too, it was not considered feminine to work outside the home, although some women did so to supplement the family income and help put food on the table.

History books written at the time (and for a long while thereafter) were all about men. We read of the wars they waged and fought; how they constituted the labour force on the mines in the developing cities and the new government they set up in 1910 (without consulting any women). If women featured at all it was as victims of man-made wars (such as the victims in the camps). Women were not expected to be assertive and take matters into their own hands.

Two examples will illustrate the subordinate position of women at the beginning of the century. Black women, most of whom were still living in the reserves, had begun to form groups to take on some church-linked social roles in the community, but they were not accepted as members of the African National Congress (ANC) when it was formed in 1912. This acceptance only came in 1943. Black men realized the need to unite politically to form a common front against white oppression, but amazingly there was no place for their women in their plans to do so. Similarly, white South African women were not permitted to play any part in political decision-making in a male-run Union government. It was only in 1930 (many years after settler women elsewhere in the empire) that white women gained the vote. This law was only grudgingly passed, by an all-male, all-white parliament, after a concerted 20-year campaign by dedicated feminists.

In the pages that follow you will learn why and how South African women of all races began to break out of the confines of stereotyped gender conventions and gradually became more assertive and demanding, taking an increasingly significant role in our history.

Organizing women for a common goal in the 20th century

It is difficult to pin down the particular issues that South African women faced then in 1956 or today. Issues that concerned women in the 1950s can be described as 'bread and butter' matters, such as housing, food prices, and permits. In modern day South Africa, women are faced with a wide range of issues such as domestic violence, child abuse, HIV/AIDS, unemployment gender discrimination as well as poverty. It is against this background that women then organised themselves within the community to take up these challenges. One such community-based structure was the Alexandra Women's Council (AWC), which was established in the mid-1940s. The AWC became active in issues relating to squatter movements, and in 1947 it demonstrated against the Native Affairs Commission, which wanted to remove squatters in Alexandra Township. Following the Second World War rapid urbanisation took place as more people moved into the cities in search of work in factories or in the mines. The influx of Black people increased to 23.4 per cent in 1946 from 18.4 per cent in 1936. As a result, the need for housing also grew. As government prevented Black people from permanent residence in the cities, they began to build squatter camps or informal settlements on the outskirts of urban areas. The reaction of the government was to clamp down on these squatter camps and remove people to locations, far from their places of work. Women took it upon themselves to fight these removals because it affected their livelihoods such as the shebeens. Women who could not find employment in the factories or as domestic workers began to brew beer and sold it to a large number of migrant workers who could not afford to buy the western beer, or to those men who still preferred the traditional African beer. Relocating these men meant a loss of customers. In the Western Cape, the women of Crossroads squatter camp established the Women of Crossroads Movement to fight similar issues as the AWC was fighting.

From left to right: Woman brewing beer in the township; Men drinking traditional beer in the shebeen; Police arresting a woman for running a shebeen.

From left to right: Woman brewing beer in the township; Men drinking traditional beer in the shebeen; Police arresting a woman for running a shebeen.

Apart from forming movements such as the AWC and the WCM, there were other movements, which grew into political movements. For instance, Thursdays in South Africa was regarded as a holy day where women from different ethnic and social backgrounds met for a prayer. These prayer groups paved the way for new structures around micro finance and economic support. They organised stokvels and savings clubs for women. Ordinary women who did not belong to any political organisations in the 1950s started these structures. There was one organisation that was established by two women who were politically active at that time; the Zenzele Club started by Josie Palmer (Mpama) and Madie-Hall Xuma. Although it was started by political figures, its members were attracted by the issues of survival that it raised. Zenzele Club encouraged women to make a living from knitting. It was through such organisations that FEDSAW rallied women for a common goal. Although the issues that women fought for remained unsolved, the march in 1956 was a victory in its own right. More women became active in politics and some paid the price of long-term imprisonment while some pose a threat to the government and were assassinated.

Women's group in Newlands, Johannesburg.

Women's group in Newlands, Johannesburg.

It was not only African women who formed social structures like the ones described above. Luli Callinicos in her book, A Place in the City: The Rand on the Eve of Apartheid, describes how Afrikaans women formed 'wives clubs' to support the Afrikaner cause of 'Broederbond'. Callinicos writes that as early as the 1930s Afrikaans women were regarded as the main bearers of their culture. They were also the "transmitters of the mother tongue and the bearers of Afrikaner culture in the home" (Callinicos; 1993:117). White women’s organisations such as the Black Sash, mobilised women structures such as these for a political cause. Although this was a challenge because of cultural barriers that bound most Afrikaans women, there were some such as Bettie du Toit who rose above those restrictions and fought for the emancipation of South African people across racial lines.

Women's Monument, Union Buildings in Pretoria Source: Sue Krige

Women's Monument, Union Buildings in Pretoria Source: Sue Krige

South African women, across racial lines, have been the source of courage for the entire community. In appointing women into government President Thabo Mbeki stated "No government in South Africa could ever claim to represent the will of the people if it failed to address the central task of emancipation of women in all its elements, and that includes the government we are privileged to lead." (Mbeki, 2004) Currently women in Cabinet make up 33 percent of positions a far cry from when Helen Suzman stood alone as a woman Member of Parliament. She made her presence felt by openly opposing the policies of the National Party and urging the government to open discussion with the Liberation Movements. Women of South Africa across all spheres of life have contributed in the making of South Africa. Today, the contribution that women made in our history is not only visible in our society but in the steps of the Union Buildings.

1910s - Anti-pass campaigns ↵

By the turn of the century, despite the fact that women of all races were still virtually restricted to the home, migrant labour had already begun to forge differences between the experience of African and white women. African men were no longer part of the traditional homestead economy. Instead they were away for extended periods of time, working under contract on the mines. In both town and rural areas the traditional pattern of the African family was destroyed, and this, in turn, undermined the very basis of tribal society. As Walker puts it, ‘African marriage became less and less stable an institution, with women gaining personal independence at the expense of the economic and emotional security within the pre-colonial family' (Walker 1990:19).

For African women in the reserves, where they soon began to outnumber the men, life was very tough. The burden of agricultural work and the responsibility of keeping the family together fell entirely on their shoulders. Many African women began to consider the alternative of moving into locations near to the towns. This provided the opportunity to take in laundry or opt for employment as domestic servants. But it suited the government better to have African families living in the reserves so the women who moved to the town were confronted by government influx control measures. In the towns women also grew more independent and assertive; they became more politically aware and less compliant with the harsh, discriminatory restrictions placed on them by officialdom.

Women demonstrated against having to carry passes in three major campaigns, all of which are mentioned here. The first, in 1913, was in Bloemfontein and stands out not only because it was such an early outbreak of women's resistance, but also because of what Julia Wells calls its ‘strength and militancy' and because it was so ‘costly to the personal lives of participants' (Wells 1993:3). It also set the tone for later anti-pass action by militant African women. The second episode, which will be mentioned later (because the material is presented chronologically) was in 1930 in Potchefstroom, a small white-dominated town where officials tried to bully the women to comply with the particular labour needs of the town. In this case the grievance of the women was against lodgers' permits. The third campaign was masterminded in Johannesburg from 1954-1956, culminating in the march in 1956 of nearly 20 000 women to Pretoria. This will receive close attention as the archive was created in celebration of this event.

In each of these episodes women reacted not because of major political issues or broad developmental policies but because the stability of their homes and families were in jeopardy. As Julia Wells puts it: ‘When it was women who resisted, it was because the crisis reached into the inner sanctum of home and family life. Each of the three [episodes of resistance]… reflects a time when women themselves were directly and negatively affected by shifts in the application of the pass laws' (Wells 1993:9).

The 1913 Bloemfontein anti-pass campaign

The women involved in this incident were an urbanised group living in the Waaihoek Location under the control of the Town Council of Bloemfontein. In 1913, partly as a measure to protect the increasing number of ‘poor whites' from black competition in the labour market, government officials in the Orange Free State declared that women living in the urban townships would be required to buy new entry permits each month. It was claimed that this would cut down on informal means of employment such as laundry work, illegal beer brewing and prostitution. Each month, when renewing her permit, a woman had to prove that she had ‘legal' employment. All ‘informal' employment was thus restricted, forcing the women to take on domestic work in Bloemfontein, which suited the ruling party, which took the women away from their own homes and children. Those who refused to comply would be evicted and sent back to the reserves. Furthermore there were allegations of sexual abuses related to the enforcement process by both white and black constables.

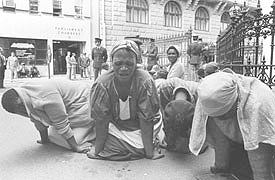

In angry response to these prescriptive measures the women sent an all-woman deputation to the governor-general. They collected more than five thousands signatures on petitions, and organised impressive demonstrations to protest the permit requirement. Both the newly formed ANC and the African Political Organisation (APO) formed in 1902, under Abdurahman, gave encouragement to the efforts of the Waaihoek women. Abdurahman was a great admirer of Gandhi’s passive resistance and he encouraged the women to invite arrest by defying the hated regulations. African people across the board also felt bitter and disappointed about the recently passed Natives Land Act (1913), so tensions were high.

On 28 May 1913 a mass meeting of women was held in Waaihoek and it was decided to adopt a passive resistance stance. They would refuse to carry residential permits. Two hundred angry women marched into town to see the mayor, but when he was eventually cornered he maintained that his hands were tied. The women promptly tore up their passes, shouted remarks at the policemen and generally provoked the authorities into arresting them. Eighty women were arrested. There was another march the next day which soon turned ugly, with sticks being brandished. The women reputedly shouted at the police: ‘We have done with pleading. We now demand!'

Unrest spread to other towns throughout the province and hundreds of women were sent to prison. Civil disobedience and demonstrations continued sporadically for several years. Ultimately the permit requirement was withdrawn. Women had succeeded in making their voices heard and this certainly inspired them for the future.

A pass book

A pass book

The term ‘pass' was used to describe any document that curtailed an African's freedom of movement and had to be produced on demand by police or local officials. As far as black people were concerned residents' permits (also called ‘lodgers' permits'), special entry permits, permits to seek work and reference books all fell into the general category of the ‘pass'. Until the 1930s women were generally exempt from pass control but the Orange Free State was the exception; here there was a complex net of restrictions on African people, both men and women. Ultimately, however, all African women in the towns or so-called ‘white' rural areas and reserves were required to carry reference books, while only certain women in the proclaimed areas were subject to the permit requirements. The issue of permits in the urban areas began a few years before reference books were introduced. African women felt that the permits were simply forerunners of reference books and treated them with equal contempt.

The Bantu Women's League (BWL)

One of the direct consequences of the Bloemfontein anti-pass campaign was the formation of early women's political movements. Women had proved their ability to take their fate in their own hands. An organization called the Native and Coloured Women's Association was formed in 1912 to lay plans for the Free State anti-pass petitions and the deputation to the governor-general. Soon afterwards it was followed, and eventually superseded by a new, very significant women's movement, the Bantu Women's league (BWL). This was formed in 1913/14 as a branch of the ANC. At the time women were not accepted as full members of the ANC, but at least the BWL made the men realize that African women were becoming assertive and politicized. The BWL became involved in passive resistance and fought against passes for black women, but it also undertook the more traditional roles of catering and entertainment for the male-dominated ANC deliberations. During this time the BWL was under the leadership of Charlotte Maxeke, South Africa's first women graduate, who had been educated in the USA. In 1918 Maxeke headed a deputation of women who went to see Prime Minister Louis Botha to plead the women's case. Following this, the Free State regulations on resident permits for women were relaxed.

The BWL appears to have survived until the early 1930s, but was absorbed into the National Council of African Women (NCAW), a less assertive movement that was inaugurated in 1933 and focused primarily on welfare issues. This body, also headed by Charlotte Maxeke, worked in cooperation with the white liberals in the Joint Councils Movement.

The 1920s - Women, employment and the changing economic scene ↵

In the 1920s, with the First World War (1914-1918) over, the pattern of female employment began to change. The war and the protectionist policy of the Pact government under JBM Hertzog (who wanted to help the ‘poor whites' to get back on their feet) both boosted the growth of the manufacturing industry. Women of all racial groups slowly began to gravitate to the towns and were drawn into the labour market. Outside the reserves economic opportunities opened up for African women too. Instead of struggling in the reserves without their men (most of whom had gone to the towns find employment, or worked on the mines) they could live in a location (where admittedly housing was scarce and conditions were poor) and seek jobs in the nearby towns. In the 1920s there were not yet any restrictions on the mobility or settlement of African women.

The pace of urbanisation and the changing female employment patterns are closely linked. Gender inequalities were, however, very marked. Across the spectrum of the entire labour market, women, whether African, coloured or white, were paid the lowest wages and were given the least skilled jobs. More than 50% of women who were employed outside the reserves in the early 1920s were in domestic service, but other avenues of employment had begun to open up. By 1925, for example, about 12% of women of all racial groups had taken jobs in the industrial sector. This exposure to city life and the bustling economy as we shall see, made women more self-assured and they became more politicized and assertive … more prepared to fight for socio-political rights as well as equal rights for women (Walker 1991:14-15).

The clothing industry became an important area of industrial employment for women, as were the food, drink and tobacco industries. Through their employment in industry women became drawn into trade unions, and this too, became a significant motivating factor in women's resistance against gender inequality and social injustice. The influence of the trade unions began to be felt by the 1920s (and the increased rapidly in the 1930s and 1940s), with women such as Ray Alexander, Hetty McLeod, Frances Baard and Bettie du Toit taking the lead and thus empowering the women's movements. Early female activists such as Charlotte Maxeke, the leader of the Bantu Women's League (BWL), also had close links with the Industrial and Commercial Workers' Union (ICU). The ICU was very influential in channeling African political aspirations in the 1920s, although thereafter it faded from the scene.

In the 1920s women also became involved in the early Communist Party of South Africa (CPSA). Its radical socialist ideas drew many African supporters in the industrial sector. Prominent women members were Ray Alexander, Mary Wolton and Josie Palmer. However, the CPSA, with its extreme socialism and radical class analysis dictated by the Communist International, fell out with the more enlightened and cautious, consultative approach of the ANC. The CPSA went into decline in the late 1930s, and was later reconstituted (in 1953) as the less extreme South African Communist Party (SACP). The SACP then declared itself willing to co-operate with the ANC and SAIC to bring about political change.

Women and rural activism: The Herschel district in the 1920s

It was not only in the towns that women became more assertive and pro-active. Historian William Beinart has researched the role of African women in rural politics in the Herschel district of the eastern Cape in the 1920s and 1930s (Bozzoli 1987: 324-357). The increasing level of male migrancy in the region had left many of the women in this remote rural area poverty-stricken and unable to feed their families. The women were dissatisfied with their treatment at the hands of the local traders to whom they sold their surplus produce (such as maize, sorghum and wheat) and from whom they purchased their basic commodities. The trading was completely unregulated and according to the women, the traders kept their prices for produce received extremely low; at the same time they raised the prices of the commodities the women had to purchase from them. Bad harvests and drought were followed by years when there were good harvests. To avoid paying higher prices the traders would stockpile produce to see them over the lean years … leaving the African families without any cash to purchase basic necessities. The women felt that the traders were taking unfair advantage of their plight and in 1922, under the leadership of local women such as Mrs Annie Sidyiyo, they decided to launch a total boycott of the trading stores. Similar action took place in the Qumbu district.

In retaliation the traders had the police charge women who forcibly removed goods that anyone tried to purchase from the stores (thus breaking the boycott). But the arrests and subsequent court appearances merely increased the women's solidarity. In the end it was the traders who agreed to regulate prices.

Women and the Potchefstroom anti-pass campaign, 1928-1930

In Potchefstroom in 1928 the municipal authorities' demand that women should pay a monthly fee for a lodger's permits was responsible for determined resistance initiated and led by women. Josie Palmer, a young coloured woman who was a local resident and prominent member of the CPSA took the leading role, and despite the fact that an ANC member, a Mrs Bhola, was also among the main organizers, it is clear that there was considerable Communist Party backing for the initiative. According to Julia Wells there was more militancy, violence and bloodshed than in Bloemfontein (1913) because international communism had influenced the women to join with the men and take the bold step of withdrawing the town's entire black labour force, leading to a situation of near panic among whites. A mass meeting was held in the location on 16 December 1929 and the organizers urged: ‘You have no guns and bombs like your masters but you have your numbers, you have your labour and the power to organize and withhold it'. Violence erupted at the meeting and the police stepped in. Five black people (one of whom later died) were injured in the gunfire as white townspeople squared up against the militant blacks (Wells 1993:73-74). A general strike then followed, continuing until January 1930.

The rising popularity of communism in the Potchefstroom location, where there was ‘dire poverty and neglect' was of great concern to the government and the Department of Native Affairs intervened directly; within a year the town women's demands and the offending legislation was repealed. According to Wells, ‘Pretoria officials recognized that meddling with black women's status endangered public order, not only because of the protests from the women, but also because of the threat of strike action from their working husbands (Wells 1993: 66-67; 73-74).

The role of women in the Natal beer riots in 1929

ICU women members, beer halls and boycotts. 1929. © UNISA

ICU women members, beer halls and boycotts. 1929. © UNISA

The regulations placed on the brewing of home-made beer in Natal rural districts and small towns in 1928/29 were the backdrop to another hotbed of resistance on the part of African women. Beer-drinking was a popular social practice among Zulu men, while beer-brewing gave women an opportunity to make a small income and thus allow them to assert their independence. As for the government, it realized that by taking over the informal liquor trade it could curb the women's aspirations for financial, social and political empowerment and at the same time set up its own beer-canteens. Control over Africans within the reserves and the townships could thus be strengthened. To top it all, a tidy profit could be made to boost funds and put more restrictions in place.

With the 1928 Liquor Act in place, police raids duly began. The privacy of homes was invaded; houses were wrecked, floors dug up, furniture smashed and liquor confiscated. There were also allegations of sexual harassment by police. Quite apart from the damage to their property, the new regulations hit the women very hard. The production and consumption of utshwala was restricted to municipal canteens. Not only did women lose their income from selling the home-brew, but they also had to watch their husbands using their wages in the canteens, thus making the authorities richer. Moreover the women were enraged that the canteen sold utshwala to its customers at for to five times its cost price. In her article on the beer protests Helen Bradford explains that the women were determined not to be entirely under financial control of the male workers; they wanted the opportunity to be independent and this, more than anything else, motivated them to protest (Bradford in Bozzoli 1987: 292-323).

They decided to take the matter into their own hands. Backed by the Natal branch of the ICU and joined by some men, they were determined to resist the new regulations, boycott the canteens and force them to close. Bradford claims that the church, and particularly Christianity, was a unifying force among many of the women. One of the main organizers was Ma-Dhlamini who was reputed to be in the forefront of all the demonstrations.

In 1929, beginning in Ladysmith, a rash of resistance began to spreading through Natal, focusing on small towns like Weenen, Glencoe, Howick, Dundee. Women marched into the towns in an overtly militant manner, shouting war chants and brandishing their sticks. They raided the canteens and assaulted the male customers. In Durban on 17 June 1929 chaos erupted with 2 000 whites clashing with 6 000 Africans on 17 June 1929. More than 120 people were injured and eight died in the protracted unrest. Cases were heard by local magistrates and some towns issued beer-brewing permits. Sentences were often suspended and a conciliatory approach was followed although some women received harsh sentences. By and large the municipal canteens and the liquor-brewing regulations apparently remained in place.

The 1930s - Trade unionism blossoms and women become more assertive ↵

Natal Trade Unionists. 1930s. ©

Natal Trade Unionists. 1930s. ©

The early 1930s were difficult years. There was a worldwide depression and South Africa did not escape its effects. Unemployment soared and there was widespread poverty. Although urban dwellers felt the pinch too, it was the families in the rural areas and particularly those in the reserves that suffered the most. African women struggled to feed their families and often the only option was to go into the towns to look for some means of supplementing the family income; often domestic service proved to be the answer. In the 1930s the government made some attempts to stem the flow of African women into the towns, but as women (unlike men) did not yet have to carry compulsory passes, female migration to the towns continued.

Many Afrikaners who were still on the land also began to drift into the towns, creating what was called the ‘poor white' problem. Urbanisation thus received another boost. Afrikaner women, like their African, Indian and Coloured counterparts, began to enter the labour market in increasing numbers, often finding work in the industrial sector. As women and mothers they had to find a way to escape the endless grind of poverty and give their children a better chance in life. In her article on Afrikaner women in the Garment Workers' Union (GWU) Vincent (2000:61) quotes a particularly poignant (translated) piece from an Afrikaans trade union newsletter:

No beard grows upon my cheeks

But in my heart I carry a sword

The battle sword for bread and honour

Against the poverty which pains my mother heart.

Bread and butter issues motivated women's to resist in the difficult 1930s. They were primarily concerned with pressing social concerns that affected the entire community: rents, the cost of living, discrimination in the workplace, passes and controls placed on earning a few pennies in the ‘informal' sector. This is why the socialist ideas of the CPSA and the work-oriented trade union movement appealed to women workers across the board. The main movements through which women expressed their growing political awareness in the 1930s were therefore the ANC, the CPSA and the trade union movement. The role of these movements in women's resistance, tenuous in the late 1920s and 1930s, began to escalate in the 1940s and will be discussed in the next section.

Women in the schizophrenic 1940s - World War II and its aftermath ↵

District Committee of the Communist Party. Josie Palmer is the first person on the right in the front row. 1945. © Communist Party Publication

District Committee of the Communist Party. Josie Palmer is the first person on the right in the front row. 1945. © Communist Party Publication

The 1940s opened with the devastating Second World War in full swing. This decade also marked the gradual transition from a mining and agricultural economy (before the war) to a flourishing industrial economy with the development of many new secondary industries in its aftermath. By this time the reserves were so depleted that they no longer provided a subsistence base for African families; they lived in extreme poverty. Urban blacks in the townships also lived under appalling conditions and Coloured and Indian people fared little better. Walker (1991:71) quotes 1940 statistics showing that 86, 8% of ‘non-Europeans' in the urban areas were living below the bread line.

Politically, the 1940s were also ‘schizophrenic' (showing different faces). The government and the black opposition moved even further apart. This trend was accentuated by significant shifts in both black and white politics.

Black politicians became increasingly more militant with the formation, within the ANC, of the Congress Youth League (CYL) in 1943.This group of young, more assertive black leaders were destined to revive the ANC (which had fallen into lethargy in the previous decade) and the CYL began to set the tone for a new spirit of resistance. African women were quick to follow this lead and in 1943 began to press for the formation of a women's league within the ANC structures so that they, too, could join the struggle against oppression.

Black trade unions grew rapidly, fuelled by the growing numbers of urban workers. They were becoming increasingly dissatisfied with the status quo and a number of major strikes and boycotts were held in the 1940s, notably the strike of African mineworkers in 1946. As we shall see, women workers of all races, now a permanent part of the industrial scene, were not slow to play their part in this climate of unrest. Within the trade unions the names of militant working women such as Frances Baard, Lilian Ngoyi and Bertha Mashaba began to be heard. In fact the 1940s and 1950s highlight the changing role of African women, and particularly working-class black women, in South Africa's political economy.

In the 1940s the South African Indian Congress (SAIC) also became more assertive and militant, and in cooperation with the ANC and CPSA took an active part in the growing culture of anti-government resistance.

White politics took a dramatic new turn in 1948. The National Party won the whites-only election in 1948 and began systematically to entrench its control. The segregation policies of previous white governments now hardened into the birth of the apartheid regime and as the 1940s gave way to the 1950s the government began to implement a wide range of oppressive apartheid legislation, including attempts to control the mobility of African women and create a stable urban proletariat. The stage was thus set for popular resistance that was to last until 1994 - resistance in which women played an important part.

Women, the war, and grassroots protests in the 1940s

During the war the cost of living soared and economic hardship increased and women struggled to feed their families. Women in the sprawling squatter camps or informal settlements on the outskirts of the urban areas took on a variety of informal jobs in order to survive. And it was clear that in such dire poverty these women were becoming more politicised. Walker (1991:73-76) claims that most political organisation among women took place at community level and she calls these ‘grassroots protests'. In Cape Town Women's Food Committees were formed that had links with the trade unions and the CPSA and demonstrated outside parliament about inadequate food supplies. In Johannesburg, women formed the People's Food Council in 1943 in an effort to improve the distribution of food; among other activities it held a conference on the food situation and organised raids on Fordsburg shopkeepers who were suspected of hoarding food. In 1943 the residents (including many women) of Alexandra Township challenged an increase in the bus fare into Johannesburg and boycotted the buses until the bus company relented.

Women were active in a number of squatter movements in and around the cities. In Cape Town, Dora Tamana, with CPSA cooperation, organised activism in a squatter camp called Blouvlei. And near Johannesburg black women applauded and supported James Mpanza's establishment of Shantytown in 1944 in defiance of the regulations against squatting. The Alexandra Women's Council (AWC) was established at about this time too, and became active in issues relating to housing and squatting. Women also organised a march through Johannesburg in 1947 to protest against the housing shortage, a campaign in which Julia Mpanze was prominent.

The restrictions on the home-brewing of beer also roused women into taking action against the authorities. There was unrest in Springs in 1945 when local women, with CPSA backing, organised a boycott of the municipal canteens. This led to police action and many of those who were arrested were women.

The ANC Women's League

Part of the rejuvenation process of the ANC in the 1940s was to build up mass membership and the role of women and their potential as a powerful agent of change was at last recognised. Previously women had not been accepted as full members but at an ANC conference held in 1943 it was decided that this should change. At the same time the ANC Women's League (ANCWL) was formed as a sub-section of the ANC, with Madie Hall-Xuma as its first president. All female members of the ANC thus became ANCWL members. It was also made clear from its establishment that the national struggle for freedom rather than women's rights would be its focus. Nor was the ANC prepared to have the ANCWL become part of a general non-racial women's movement; it was to be an exclusively ANC body.

It apparently took some years before the league was fully operational, during which time its activities were confined to the usual ‘women's work’ such as fundraising and catering, functions that were supportive rather than innovative. Provincial congresses were only established after the war in the late 1940s, although there are indications that women participated in discussions about the campaign against passes for men (in the 1940s women did not yet have to carry passes themselves) that were held in 1944. But in 1949 the CYL introduced its Programme of Action, a new ANC president took over and this spirit of revival filtered through to the women's league. Furthermore, the dynamic Ida Mtwana took over the leadership. Provincial branches of the ANCWL were established, incorporating township women countrywide; working-class women with their trade union background also brought a more assertive and impatient attitude into the ANCWL. In 1950 rumours were also rife that the new government was planning to enforce much tighter control of African women's mobility – in other words to make women, like the men, carry the dreaded passes. This news set off a wave of anger that boosted the ANCWL's profile as a viable resistance organisation. We shall see how the ANCWL expanded in influence and effectiveness in the rising tide of black resistance of the 1950s.

Indian women and passive resistance in the 1940s

Indian Passive Resistance. A mass meeting in Johannesburg. 1946-1948. © The University of Kwazulu Natal documentation centre.

Indian Passive Resistance. A mass meeting in Johannesburg. 1946-1948. © The University of Kwazulu Natal documentation centre.

Although Indian women had become involved in Gandhi's passive resistance of 1913 they did not attempt to form any long-term women's organisations or play an overt political role again until the 1940s. The SAIC also experienced a period of relative inactivity until the Second World War. The war itself had a radicalising impact on the SAIC and as had happened in the ANC, more assertive leaders took over from the old guard of the SAIC.

In 1946 the new leadership challenged the harsh, segregationist Asiatic Land Tenure and Representation Act (the so-called Ghetto Act) that was passed by the government. This law established separate areas of land tenure in Natal towns and placed severe restrictions on Indian settlement. It offered Indians a very insignificant form of ‘representation' in appeasement, but this was promptly rejected. The SAIC decided to capitalise on the wave of anger that had arisen in the Indian community and launched a campaign of passive resistance. The campaign had an important impact on Indian women, initiating a new political activism in their ranks. Dr Goonam, a young medical doctor, was the main organiser, and in March 1946 a well-attended meeting of Indian women was held. Goonam, Fatima Meer and Mrs NP Desai were the speakers. The women pledged their support for the initiative and many women volunteered.

Zainab Asvat, a young medical student was one of the women among the group who set up camp on 13 June 1946 on the plot at the corner of Umbilo Road and Gale Street. They proposed to live there in tents until such time as they were arrested. There were eighteen resisters, six of whom were women: Zainab Asvat, Zohra Bhayat, Amina Pahad, Zubeida Patel of Johannesburg and Mrs Lakshmi Govender and Mrs Veeramah Pather of Durban. Dr GM Naicker, President of the NIC and MD Naidoo, Secretary of the NIC, were the leaders of the group.

On the night of Sunday, 16 June, white hooligans overran the camp. After this attack, the leaders asked the women to leave the camp but they refused to go. At a subsequent meeting Zainab Asvat made a fiery speech in which she denounced the violence, denounced discriminatory laws, affirmed the resisters' commitment and appealed to the people to remain calm but to take note of the circumstances. Zainab was arrested and released later the same night. Her courage and determination were inspirational and several women joined in the campaign. Other Indian women who took a leading role were Mrs Veeramah Pather, Miss Khatija Mayet, Dr K. Goonam and Miss Zohra Meer. In July 1946, Zainab again led a batch of resisters, was arrested, sent to prison for three months. Zainab, Mrs PK Naidoo and Miss Suriakala Patel, were later elected to the Transvaal Indian Congress Committee.

Goonam deputised on several occasions while senior NIC men were overseas, and later became the vice-president. These prominent Indian women also made contact with women in the CPSA and the ANC and were drawn into women's issues like the anti-pass campaign. Amina Cachalia, sister of Zainap Asvat, and Fatima Meer became particularly prominent in the 1950s when women across the race spectrum united under the banner of the Congress Alliance.

The turbulent 1950s - Women as defiant activists ↵

The crowd outside the courts “standing by their leaders”. The Treason Trial. 1955. © Bailey's African History Archives.

The crowd outside the courts “standing by their leaders”. The Treason Trial. 1955. © Bailey's African History Archives.

In the 1950s the government's increasingly repressive policies began to pose a direct threat to all people of colour, and there was a surge of mass political action by blacks in defiant response. The 1950s certainly proved to be a turbulent decade. We shall see that women were prominent in virtually all these avenues of protest, but to none were they more committed than the anti-pass campaign.

Women and the anti-pass campaign 1950-1953

The apartheid regime's influx control measures and pass laws were what women feared the most and reacted to most vehemently. Their fears were not unfounded. In 1952 the Native Laws Amendment Act tightened influx control, making it an offence for any African (including women) to be in any urban area for more than 72 hours unless in possession of the necessary documentation. The only women who could live legally in the townships were the wives and unmarried daughters of the African men who were eligible for permanent residence.

In the same year the Natives (Abolition of Passes and Coordination of Documents Act) was passed. In terms of this act the many different documents African men had been required to carry were replaced by a single one - the reference book - which gave details of the holder's identity, employment, place of legal residence, payment of taxes, and, if applicable, permission to be in the urban areas. The act further stipulated that African women, at an unspecified date in the near future, would for the first time be required to carry reference books. Women were enraged by this direct threat to their freedom of movement and their anti-pass campaign, as Walker puts it ‘was one of the most vociferous and effective protest campaigns of any at the time' (1991:125).

Protests started as early as 1950 when rumours of the new legislation were leaked in the press. Meetings and demonstrations were held in a number of centres including Langa, Uitenhage, East London, Cape Town and Pietermaritzburg. In the Durban protests in March 1950, Bertha Mkize of the ANCWL was a leading figure, while in Port Elizabeth Florence Matomela (the provincial president of the ANCWL) led a demonstration in which passes were burnt. By 1953 there were still sporadic demonstrations taking place and these accelerated when local officials began to enforce the new pass regulations. Reaction was swift and hostile. On 4 January 1953, hundreds of African men and women assembled in the Langa township outside Cape Town to protest against the new laws. Delivering a fiery speech to the crowd Dora Tamana, a member of the ANC Women's League and later a founding member of the Federation of South African Women, declared:

We women will never carry these passes. This is something that touches my heart. I appeal to you young Africans to come forward and fight. These passes make the road even narrower for us. We have seen unemployment, lack of accommodation and families broken because of passes. We have seen it with our men. Who will look after our children when we go to jail for a small technical offence - not having a pass?

The Defiance Campaign is launched and women step forward

Women during the Defiance Campaign 1952. Photograph by Bob Gosani © Baileys Archives.

Women during the Defiance Campaign 1952. Photograph by Bob Gosani © Baileys Archives.

In June 1952 the ANC and SAIC initiated a cooperative initiative known as the Defiance Campaign. Radical tactics of defiance were to be employed to exert pressure on the government. This was in line with the ANC's declared ‘Programme of Action' of 1949. Volunteers from the ANC and SAIC (the CPSA had disbanded in 1950) began to publicly defy discriminatory laws and invite arrest, filling the jails and over-extending the judicial system.

Women were prominent in many of these defiant incidents. Florence Matomela was among 35 activists arrested in Port Elizabeth and Bibi Dawood recruited 800 volunteers in Worcester. Fatima Meer, an Indian woman, was arrested for her role in the unrest and was subsequently banned. Another woman to come to the fore during the Defiance Campaign was Lilian Ngoyi, who later became president of both the ANCWL and FSAW. She had previously kept a very low profile and been involved in church-related organisations, but the Defiance Campaign made her realize that only by adopting a more aggressive and militant approach would the government be fully aware of the commitment of women to the national struggle for freedom. Women's involvement in the Defiance Campaign certainly proved to be an important stimulus in their political development across the board. It not only strengthened the ANCWL but also motivated women to establish the FSAW.

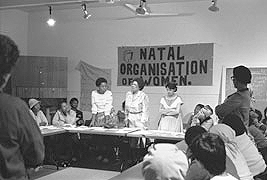

The Federation of South African Women (FSAW or FEDSAW)

Three important female activists were in Port Elizabeth in April 1953 at the time when the Defiance Campaign was underway and there was widespread political unrest in the region. Influx control measures had just been implemented in the region a few months before and had created a storm of protest from the people. The three women were Florence Matomela (eastern Cape president of the ANCWL), Frances Baard, who was a leading local figure in the Food and Canning Worker's Union (FCWU) and Ray Alexander, the general secretary of the FCWU, who was in Port Elizabeth to attend a trade union conference. The three decided among themselves that the time was right to call women to a meeting to discuss the formation of a national women's organization. No record was kept of the informal meeting held that same evening, but Ray Alexander later said that it had been attended by about 40 women. Other than Alexander, a Mrs Pillay, a Miss Damons and Gus Coe, most of the women were Africans. Although from various different organizations all the women were committed to the Congress Alliance and the Defiance Campaign that had been initiated the previous year. Ray Alexander pointed out the advantages of an umbrella body that would devise a national strategy to fight against the issues of importance to women: every-day matters such as rising food and transport costs, passes and influx control. The women were enthusiastic in their response and Ray Alexander was asked to pursue the matter further.

Ray Alexander was based in Cape Town so the planning for the initial conference was done there. Hilda Watts (Bernstein), also a communist and an experienced political campaigner, was asked to handle the Johannesburg wing of the committee. Subsequently Johannesburg and Cape Town were to become the main FSAW centres. An energetic, skilled organizer who had been a tireless campaigner for women's rights since the 1930s, Ray Alexander was the ideal woman for the job. She co-opted a number of influential women country-wide to help her but her individual contribution was enormous. All the major organizations were represented in her ‘women's committee' including the ANC Women's Leaguers, trade unionists, members of the SAIC, of the Transvaal All-Women's Union and of the Congress of Democrats(COD). The COD had been formed when the CPSA had disbanded in 1950; it thus included many of the ex-Communist Party members.

The committee met regularly to plan the coming conference. Other notable women involved were Ida Mtwana (ANC Women's League), Josie Palmer (ex-CPSA and Transvaal All-Women's Union), Helen Joseph (COD), Amina Cachalia and Mrs M Naidoo (SAIC) and three trade unionists: Bettie du Toit, Lucy Mvubelo and Hetty du Preez. Ray Alexander also went to Durban to coordinate plans with women in Natal, where Dr K Goonam, Fatima Meer and Fatima Seedat of the SAIC and Bertha Mkize and Henrietta Ostrich of the ANC, were consulted for their views. Invitations to the inaugural conference of the FSAW were sent out in March 1954, signed by 63 women who supported the aims of the Congress Alliance.

The Federation of South African Women (FEDSAW or FSAW) was launched on 17 April 1954 in the Trades Hall in Johannesburg, and was the first attempt to establish a national, broad-based women's organisation. One hundred and forty-six delegates, representing 230,000 women from all parts of South Africa, attended the founding conference and pledged their support for the broadly-based objectives of the Congress Alliance. The specific aims of FSAW were to bring the women of South Africa together to secure full equality of opportunity for all women, regardless of race, colour or creed, as well as to remove their social, legal and economic disabilities.

A draft Women's Charter was presented by Hilda Bernstein, and in complete identification with the national liberation movement as represented by the Congress Alliance, the Women's Charter called for the enfranchisement of men and women of all races; for equality of opportunity in employment; equal pay for equal work; equal rights in relation to property, marriage and children; and the removal of all laws and customs that denied women such equality. It further demanded paid maternity leave, childcare for working mothers, and free and compulsory education for all South African children. These demands were later incorporated into the Freedom Charter that was adopted by the Congress of the People, held in Kliptown near Johannesburg, from 25-26 June 1955.

The administrative groundwork of the newly-established FSAW evolved over the months that followed, but a national executive committee was formed at the inaugural conference in April 1954. Ida Mtwana was elected as national president (she was also the presiding ANCWL president), which indicated the key role the ANC (the senior partner of the Democratic Alliance) was destined to play in the new organisation. Ray Alexander became the national secretary and the vice presidents were Gladys Smith, Lilian Ngoyi, Bertha Mkize and Florence Matomela.

The women were unanimous in their opinion that the inaugural conference had been an unqualified success. On Hilda Watts' suggestion men volunteers had been assigned the catering responsibilities for the conference. This was symbolic. As Ida Mtwana put it: ‘Gone are the days when the place of women was in the kitchen and looking after the children. Today they are marching side by side with men in the road to freedom' ( Walker 1991:154).

Women's role in the Congress of the People and the Freedom Charter

The launch of the Freedom Charter. 1956. © The Sowetan.

The launch of the Freedom Charter. 1956. © The Sowetan.

By the time the FSAW had been established in 1954 the Defiance Campaign had fizzled out. This is not to say that it had failed, despite it shortcomings. But the government had weathered the defiance and was introducing yet more of its apartheid measures with persistent vigour. It became clear that the national liberation movement needed to adopt a new initiative. The Congress Alliance began to organise the Congress of the People; once again women were destined to play an important role. This despite the fact that many of the leading women activists in the ANCWL and FSAW including Ray Alexander, were banned and had to cut their ties with the organisation.

In August 1954 the Congress Alliance asked the FSAW to assist in organising the Congress of the People and the women agreed with enthusiasm. They were to help organise local bodies and recruit new grassroots support for the Alliance by holding house meetings and local conferences. This they did with great success in the opening months of 1955. In addition they took on the huge task of arranging accommodation for the more than 2 000 expected delegates. Their input gave the women an opportunity to lobby for the incorporation of some of their demands into the Freedom Charter adopted at the mass meeting.

Walker (1991:183) shows that although the FSAW was closely involved in the planning of the Congress of the People, women only played a limited role in the actual meeting. On 25-26 June 1955 nearly 3 000 delegates gathered at Kliptown. There were 721 women delegates in the official tally of 2 848 – in other words only about a quarter of the delegates at the Congress of the People were women. There were a few women, including Sonia Bunting, who spoke from the floor, but Helen Joseph, who was the FSAW's Transvaal secretary, was the only female platform speaker. The clause that she proposed on behalf of women, that of the need for ‘houses, security and comfort', including free medical treatment for mothers and young children, was in fact subsequently included in the Freedom Charter. Frances Baard, a prominent trade unionist and member of the executive committee of the FSAW, was involved in the compilation of the Freedom Charter.

In September 1955 the protest against the imposition of passes for women became the primary concern for the ANCWL and the FSAW but for black women across the board. This anti-pass campaign peaked with a massive demonstration of ‘women's power' in August 1956. After the Pretoria march the campaign continued until the end of the 1950s, with in Zeerust in 1957, Johannesburg in 1958 and Natal in 1959. In 1960, as will be seen, FSAW's plans were abruptly halted in the wake of the Sharpeville unrest when the government banned the ANC. FSAW had been dealt a severe blow.

In December 1956 several female activists were involved in another high profile incident. In a determined effort to try to curtail the national liberation movement, the government rounded up and arrested 156 leaders of the Congress Alliance. Among those detained were leading women such as Lilian Ngoyi, Helen Joseph, Annie Silinga and Francis Baard. They were accused of plotting to overthrow the government, and were tried in the infamous Treason Trial that lasted for four and a half years. During this protracted period women of the FSAW and ANCWL helped to organise support for the treason trialists and their families.

The women's 1955 anti-pass campaign

In September 1955 the issue of passes burst into the public eye again when the government announced that it would start issuing reference books to black women from January 1956. Women, now politicised and well-organised into a powerful resistance movement, immediately rose to the challenge. No longer were they merely regarded as mothers, bound to the home; they were independent and assertive adult South Africans. Passes threatened their basic rights of freedom and family life and they were going to resist them with everything they had. They were unequivocal in their message to the government: We shall not rest until ALL pass laws and all forms of permits restricting our freedoms have been abolished. We shall not rest until we have won for our children their fundamental rights of freedom, justice and security.

As Walker puts it, the anti-pass protests by women in the 1950s were a good indication that they had thrown off the shackles of the past. The demonstrations that the women launched were, in her view, ‘probably the most successful and militant of any resistance campaign mounted at that time'. She sees them as the ‘political highpoint of 1956, not only for the women who took part but for the entire Congress Alliance' (Walker 1991).

The Federation of South African Women (FSAW) that had been formed the previous year was beginning to assert itself by 1955. It was by now an accepted organisation within the ambit of the Congress Alliance, regional branches had been set up and mass membership was growing throughout the country. Furthermore it had links with other major women's organisations including the powerful ANC Women's League (ANCWL). A march to Pretoria to present women's grievances had been mooted in August 1955, and when the pass issue came to the fore in September the scale and urgency of the demonstration increased dramatically.

The demonstration took place on 27 October 1955, and was a great success. This was despite organisational difficulties – including police intimidation, and the banning of Josie Palmer, one of the main organisers, a week before the date of the gathering. Furthermore, in addition to police action, the government had been as obstructionist as it could. The then Minister of Native Affairs, HF Verwoerd, under whose jurisdiction the pass laws fell, pointedly refused to receive any multiracial delegation. Pretoria City Council refused the women permission to hold the meeting and saw to it that public transport was stalled to make it difficult for the women to get to the Pretoria venue. Private transport had to be arranged and evasive tactics adopted for a multitude of other obstructionist measures launched by the authorities. In the circumstances it was surprising, and very gratifying to the organisers that a crowd of between 1 000 and 2 000 women gathered in the grounds of the Union Buildings in Pretoria. Although the majority were African women, White, Coloured and Indian women also attended. The crowd, most of whom came from the Rand towns, was orderly and dignified throughout the proceedings. They handed their bundles of signed petitions to Lilian Ngoyi, Helen Joseph, Rahima Moosa and Sophie Williams, the main organisers, who deposited them at the ministers' office doors. In the aftermath of the demonstration the government tried to downplay its influence by alleging (erroneously) that the meeting had only been successful because the organisation had been in the hands of white women. That black women of the FSAW and ANCWL had in fact played a central role was evident when a few months later Lilian Ngoyi became the first woman to be elected to the national executive of the ANC (Walker 1991).

Preparations for the 1956 Women's March

The success of the October 1955 gathering was highly motivating and buoyed up the women to capitalise on their success. From 1955 onwards the pass issue became the single most important focus of their militancy. The ANC, as the major anti-government party identified itself closely with the campaign reiterating that the pass struggle ‘was not one for women alone, but for all African people'. But at its annual conference of 1955, but did not appear to have a specific strategy in mind. In marked contrast the FSAW immediately set about working on a plan of meetings, demonstrations, and local initiatives. The women, carried along by a mass following of females countrywide, recognised the authority of the ANC but were not prepared to delay their own preparations.

Meetings held across the country on the anti-pass ticket proved to be remarkably successful, and were attended by huge crowds. Meetings in Free State towns in late 1955 and in Port Elizabeth in January 1956, Johannesburg in March 1956 and those in Durban, East London Cape Town and Germiston all went off well. The mood was militant, with Annie Silinga declaring: ‘we women are prepared to fight these passes until victory is ours' ( Walker 1991:191).

In reply the government threatened reprisals, but when it finally began issuing reference books it did so unobtrusively, starting in white agricultural areas and smaller towns, choosing Winburg in the Free State, where FSAW presence was minimal and the women were not well-informed. Here, on 22 March 1956, they issued 1 429 black women with reference books and met with little reaction. Senior ANC officials were thereupon designated to go to Winburg immediately and Lilian Ngoyi and several men arrived in the town the next week and addressed the women. Inspired by the presence of Ngoyi, who was an excellent orator, the local women defiantly marched into town and publicly burnt their new reference books outside the magistrate's office. The authorities reacted swiftly; the offenders were arrested and charged. Subsequently it was reported that their monthly pensions would not be paid to them unless they could produce their reference books. Again there was a wave of protest from all parts of the country, and anti-pass demonstrations were held in 38 different venues.

The authorities continued to send out their units to issue the hated reference books. It was unwelcome news to the FSAW organisers that the government was persevering and that by September 1956 it had visited 37 small centres and succeeded in issuing 23 000 books. Although none of the major ANC strongholds had been visited and women throughout the country were in militant mood, it was clear that drastic action would have to be taken; and fast. It decided to organise another massive march to Pretoria. This time women would come from all parts of the country, not just the Rand. They vowed that the prime minister, JG Strijdom, would be left in no doubt about how the women felt about having to carry passes.

The organization of this event was to culminate in the 1956 Women’s March. We have put together a special page on this event.

1956 - The Women's March: Pretoria, 9 August

9th August Union Buildings © Baileys Archives.

9th August Union Buildings © Baileys Archives.

‘Strijdom, you have tampered with the women,You have struck a rock.'So runs the song composed to mark this historic occasion

By the middle of 1956 plans had been laid for the Pretoria march and the FSAW had written to request that JG Strijdom, the current prime minister, meet with their leaders so they could present their point of view. The request was refused.

The ANC then sent Helen Joseph and Bertha Mashaba on a tour of the main urban areas, accompanied by Robert Resha of the ANC and Norman Levy of the Congress of Democrats (COD). The plan was to consult with local leaders who would then make arrangements to send delegates to the mass gathering in August.

The Women's March was a spectacular success. Women from all parts of the country arrived in Pretoria, some from as far afield as Cape Town and Port Elizabeth. They then flocked to the Union Buildings in a determined yet orderly manner. Estimates of the number of women delegates ranged from 10 000 to 20 000, with FSAW claiming that it was the biggest demonstration yet held. They filled the entire amphitheatre in the bow of the graceful Herbert Baker building. Walker describes the impressive scene:

Many of the African women wore traditional dress, others wore the Congress colours, green, black and gold; Indian women were clothed in white saris. Many women had babies on their backs and some domestic workers brought their white employers' children along with them. Throughout the demonstration the huge crowd displayed a discipline and dignity that was deeply impressive (Walker 1991:195).

Neither the prime minister or any of his senior staff was there to see the women, so as they had done the previous year, the leaders left the huge bundles of signed petitions outside JG Strijdom's office door. It later transpired that they were removed before he bothered to look at them. Then at Lilian Ngoyi's suggestion, a masterful tactic, the huge crowd stood in absolute silence for a full half hour. Before leaving (again in exemplary fashion) the women sang ‘Nkosi sikeleli Afrika'. Without exception, those who participated in the event described it as a moving and emotional experience. The FSAW declared that it was a ‘monumental achievement'.

The significance of the Women's March must be analysed. Women had once again shown that the stereotype of women as politically inept and immature, tied to the home, was outdated and inaccurate. And as they had done the previous year, the Afrikaans press tried to give the impression that it was whites who had ‘run the show'. This was blatantly untrue. The FSAW and the Congress Alliance gained great prestige form the obvious success of the venture. The FSAW had come of age politically and could no longer be underrated as a recognised organisation – a remarkable achievement for a body that was barely 2 years old. The Alliance decided that 9 August would henceforth be celebrated as Women's Day, and it is now, in the new South Africa, commemorated each year as a national holiday.

Passes for African Women

The Government`s first attempts to force women to carry passes and permits had been a major fiasco. In 1913, government officials in the Orange Free State declared that women living in the urban townships would be required to buy new entry permits each month. In response, the women sent deputations to the Government, collected thousands of signatures on petitions, and organised massive demonstrations to protest the permit requirement. Unrest spread throughout the province and hundreds of women were sent to prison. Civil disobedience and demonstrations continued sporadically for several years. Ultimately the permit requirement was withdrawn. No further attempts were made to require permits or passes for African women until the 1950s. Although laws requiring such documents were enacted in 1952, the Government did not begin issuing permits to women until 1954 and reference books until 1956. The issuing of permits began in the Western Cape, which the Government had designated a "Coloured preference area". Within the boundaries established by the Government, no African workers could be hired unless the Department of Labour determined that Coloured workers were not available. Foreign Africans were to be removed from the area altogether. No new families would be allowed to enter, and women and children who did not qualify to remain would be sent back to the reserves. The entrance of the migrant labourers would henceforth be strictly controlled. Male heads of households, whose families had been endorsed out or prevented from entering the area, were housed with migrant workers in single-sex hostels. The availability of family accommodations was so limited that the number of units built lagged far behind the natural increase in population.

In order to enforce such drastic influx control measures, the Government needed a means of identifying women who had no legal right to remain in the Western Cape. According to the terms of the Native Laws Amendment Act, women with Section 10(1)(a), (b), or (c) status were not compelled to carry permits. Theoretically, only women in the Section 10(1)(d) category - that is, work-seekers or women with special permission to remain in the urban area - were required to possess such documents. In spite of their legal exemption, women with Section 10(1)(a), (b), and (c) rights were issued permits by local authorities which claimed that the documents were for their own protection. Any woman who could not prove her (a), (b), or (c) status was liable to arrest and deportation.

Soon after permits were issued to women in the Western Cape, local officials began to enforce the regulations throughout the Union. Reaction to the new system was swift and hostile. Even before the Western Cape was designated a "Coloured preference area", Africans were preparing for the inevitable. On January 4, 1953, hundreds of African men and women assembled in the Langa township outside Cape Town to protest the impending application of the Native Laws Amendment Act. Delivering a fiery speech to the crowd Dora Tamana, a member of the ANC Women’s League and a founding member of the Federation of South African Women, declared:

We, women, will never carry these passes. This is something that touches my heart. I appeal to you young Africans to come forward and fight. These passes make the road even narrower for us. We have seen unemployment, lack of accommodation and families broken because of passes. We have seen it with our men. Who will look after our children when we go to jail for a small technical offence -- not having a pass?

Passes for African Women

Women's March 9th August 1956 Union Buildings © Baileys Archives.

Women's March 9th August 1956 Union Buildings © Baileys Archives.

Adopted at the Founding Conference of the Federation of South African Women

Johannesburg, 17 April 1954 (The Charter expressed the philosophy and aims of the newly established Federation of South African Women (FSAW).

It was adopted at the inaugural conference and included in the final report of the conference.)

Preamble:

We, the women of South Africa, wives and mothers, working women and housewives, African, Indians, European and Coloured, hereby declare our aim of striving for the removal of all laws, regulations, conventions and customs that discriminate against us as women, and that deprive us in any way of our inherent right to the advantages, responsibilities and opportunities that society offers to any one section of the population.

A Single Society:

We women do not form a society separate from the men. There is only one society, and it is made up of both women and men. As women we share the problems and anxieties of our men, and join hands with them to remove social evils and obstacles to progress.

Test of Civilisation:

The level of civilisation which any society has reached can be measured by the degree of freedom that its members enjoy. The status of women is a test of civilisation. Measured by that standard, South Africa must be considered low in the scale of civilised nations.

Women's Lot:

We women share with our menfolk the cares and anxieties imposed by poverty and its evils. As wives and mothers, it falls upon us to make small wages stretch a long way. It is we who feel the cries of our children when they are hungry and sick. It is our lot to keep and care for the homes that are too small, broken and dirty to be kept clean. We know the burden of looking after children and land when our husbands are away in the mines, on the farms, and in the towns earning our daily bread.

We know what it is to keep family life going in pondokkies and shanties, or in overcrowded one-room apartments. We know the bitterness of children taken to lawless ways, of daughters becoming unmarried mothers whilst still at school, of boys and girls growing up without education, training or jobs at a living wage.

Poor and Rich:

These are evils that need not exist. They exist because the society in which we live is divided into poor and rich, into non-European and European. They exist because there are privileges for the few, discrimination and harsh treatment for the many. We women have stood and will stand shoulder to shoulder with our menfolk in a common struggle against poverty, race and class discrimination, and the evils of the colourbar.

National Liberation:

As members of the National Liberatory movements and Trade Unions, in and through our various organisations, we march forward with our men in the struggle for liberation and the defence of the working people. We pledge ourselves to keep high the banner of equality, fraternity and liberty. As women there rests upon us also the burden of removing from our society all the social differences developed in past times between men and women, which have the effect of keeping our sex in a position of inferiority and subordination.

Equality for Women:

We resolve to struggle for the removal of laws and customs that deny African women the right to own, inherit or alienate property. We resolve to work for a change in the laws of marriage such as are found amongst our African, Malay and Indian people, which have the effect of placing wives in the position of legal subjection to husbands, and giving husbands the power to dispose of wives' property and earnings, and dictate to them in all matters affecting them and their children.

We recognise that the women are treated as minors by these marriage and property laws because of ancient and revered traditions and customs which had their origin in the antiquity of the people and no doubt served purposes of great value in bygone times.

There was a time in the African society when every woman reaching marriageable stage was assured of a husband, home, land and security.

Then husbands and wives with their children belonged to families and clans that supplied most of their own material needs and were largely self-sufficient. Men and women were partners in a compact and closely integrated family unit.

Women who Labour:

Those conditions have gone. The tribal and kinship society to which they belonged has been destroyed as a result of the loss of tribal land, migration of men away from the tribal home, the growth of towns and industries, and the rise of a great body of wage-earners on the farms and in the urban areas, who depend wholly or mainly on wages for a livelihood.

Thousands of African women, like Indians, Coloured and European women, are employed today in factories, homes, offices, shops, on farms, in professions as nurses, teachers and the like. As unmarried women, widows or divorcees they have to fend for themselves, often without the assistance of a male relative. Many of them are responsible not only for their own livelihood but also that of their children.

Large numbers of women today are in fact the sole breadwinners and heads of their families.

Forever Minors:

Nevertheless, the laws and practices derived from an earlier and different state of society are still applied to them. They are responsible for their own person and their children. Yet the law seeks to enforce upon them the status of a minor.

Not only are African, Coloured and Indian women denied political rights, but they are also in many parts of the Union denied the same status as men in such matters as the right to enter into contracts, to own and dispose of property, and to exercise guardianship over their children.

Obstacle to Progress:

The law has lagged behind the development of society; it no longer corresponds to the actual social and economic position of women. The law has become an obstacle to progress of the women, and therefore a brake on the whole of society.

This intolerable condition would not be allowed to continue were it not for the refusal of a large section of our menfolk to concede to us women the rights and privileges which they demand for themselves.

We shall teach the men that they cannot hope to liberate themselves from the evils of discrimination and prejudice as long as they fail to extend to women complete and unqualified equality in law and in practice.

Need for Education: