Introduction

European interest in Zimbabwe can be traced to the 18th century. This began with the arrival of Christian missionaries in 1858, who befriended King Mzilikazi. This was followed by fortune hunters and land grabbing settlers. Cecil John Rhodes who was the pioneer of the conquest of Zimbabwe, with his British South African Company (BSAC), bought a written concession for exclusive mining rights in the Matabeleland and other adjoining territories from King Lobengula. He arrived accompanied by an army and later declared war on the King. After successfully overthrowing the King he named the country Rhodesia.

This article focuses on the Pioneer Corps that Rhodes sent in to conquer what was later called Rhodesia. Significantly it explores the role of the Pioneer Corps and their relationship with Rhodes; how the conquest was achieved; the aftermath of the conquest; as well as Rhodesia under the company’s control until it lost it control.

Pioneer Corps

During WW1 corps of the British Army had labour companies and infantry regiments had their labour battalion who were tasked with field engineering. Labour corps was involved in battlefield clearance. They disbanded and later reformed and are now recognised as the predecessor of the Royal Pioneer Corps. When WW2 broke out Auxiliary Military Pioneer Corps was formed and later re-titled the Pioneer Corps. [i]

The history of pioneer corps dates back to 1854 when the Army Works Corps was formed in the United Kingdom to serve in the Crimea War. The object of forming was ‘to carry out works of a civil character at the Seat of War such as construction of roads and railways, the erection of stone houses and jetties, on which stores and material might be landed with facility.’ [ii] In 1856 the pioneer corps disbanded. In early 1916 the Military Service Act was passed and it was decided to create a non-combatant corps that would serve as the support base for the army. Their function was to handle supplies, work on roads, undertake sanitary duties and hutments as well as quarrying and timber work. [iii]

During WW1 Britain lacked an organised labour system and depended on civilians who were from France. However as the war progressed, demands for labour also increased and there were less Frenchmen to provide assistance. To address this challenge Britain sent labourers to France and as a result in 1917 a labour corps was formed. In 1918 labour corps was granted their own badge. After the creation of its badge, labour corps was split into different labour groups, each group consisting of several companies and headquarters as well as employment companies. Although the labour corps were non-combatants, they performed their duties under heavy fire. As the war reached the end the need for labour corps decreased and consequently it was disbanded.

During WW2 the labour corps was reformed and because of its association with labour it was renamed the Auxiliary Military Corps in 1939. Enemy Aliens were recruited into the corps, and by 1942 when their loyalty was confirmed, they were allowed to become fighting arms. In 1940 the colonel Commandant pointed out that the name Auxiliary Military Pioneer Corps was unpopular with all the ranks and the name was changed to Pioneer Corps. It was further agreed that companies should be armed on 100 percent scale rather than 25 percent.

Cecil John Rhodes

Cecil John Rhodes Image source

Cecil John Rhodes Image source

Born in England on 5 July 1853 Cecil John Rhodes was the fifth son Louisa Peacock and Francis William Rhodes who was a priest of the Church of England. [iv] Due to his poor health, unlike his other brothers who were sent to attend better schools, he was forced to stay at home and attend the local grammar school. His health challenges denied him an opportunity to attend college he was instead sent to work on his brother’s cotton farm in South Africa. His brother soon learnt that the business of growing cotton had little potential of building fortune, so they set their eyes on the diamond business as the diamond fever was sweeping in the Natal region. [v]

In 1871 Rhodes joined his brother’s diamond business in the fields of Kimberley. The following year he suffered a heart attack. After his recovery, he joined his brothers on a mission to find gold in the interior and this journey inspired his interest in the country and most notably in the road to northern interior. [vi] In 1873 he went back to his country of birth to complete his studies and left his diamond fields in the care of his partner Charles D Rudd. Their business venture grew and in 1880 they launched the De Beers Mining Company. His interest was not only in business, but also in politics as he was a member of Cape Parliament and later became the Prime Minister of the Cape Colony. After he supported an attack on Transvaal which was unsuccessful, he had to resign as Prime Minister of the Cape. [vii] Rhodes used his wealth to expand Britain’s empire in Africa through his British South Africa Company (BSAC), which had a police force. To this end Mashonaland, a region on Northern Zimbabwe, was colonised in the hope of extracting gold. However, the Gold had already been worked out long before his expedition. Some of the whites who accompanied the BSAC to Mashonaland decided to settle there and started farming. This caused a rebellion by the Matabele and the Mashona people as they were against the settlement of Europeans, however, they were crushed by Rhodes. His BSAC and conquered the regions, which were re-named Northern and Southern Rhodesia. [viii] This will further be visited in the text that follows.

Rhodes pioneer corps: British South African Company

The establishment

The British South African Company was formed by Cecil Rhodes in 1888. In 1889 Rhodes applied for a charter from the United Kingdom to form the BSAC and in October the same year the Royal Charter was granted. The Charter was first granted for 25 years and was later extended for another 10 years. He was given the responsibility of expanding the British empire by colonising north of the Limpopo in 1889. The BSAC was given powers to maintain law and order. [ix] and was modelled on the East India Company. To this end the company was expected to develop settlements for European settlers in Africa. [x]

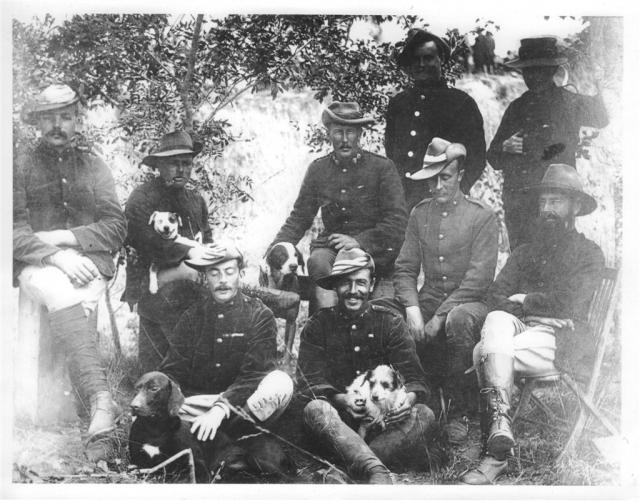

British South African Company Police Image source

British South African Company Police Image source

The company was invested with the right to create its own political administration. Profits were made from diamonds and gold and these profits were re-invested in the company, allowing it to expand its area of influence. [xi] The BSAC carried out the mandate under the control of Rhodes and by 1890 the company successfully occupied Mashonaland, which saw the expansion of European settlement into the area. The British flag was raised and the area renamed Rhodesia after Cecil John Rhodes. [xii]

The Invasion of Great Zimbabwe

The Great Zimbabwe

The name Zimbabwe derives from a historical stone structure known as Great Zimbabwe (House of Stones), which is the second largest in Africa after the Egyptian pyramids [xiii]. Zimbabwe is a Shona word, which means ‘Stone houses’. In the early times the country was home to indigenous San people who can be traced to as far back as 200 BC. The San were later moved from the area by Bantu speaking Africans (Bakalanga) late AD 1000 - 1550. [xiv] Bakalanga people descended from Leopards Kopje Farmers near the area that is known today as Bulawayo. [xv] In the early nineteenth century the region was witness to a series of invasions from Bantu-speaking people. As a result of these invasions a variety of different ethnic groups became scattered around the region.

British conquest began in 1890 with the arrival of Cecil John Rhodes. This marked the beginning of the eighty years long colonial rule, which led to the gradual expansion of white population settling in the region and the development of an economy based on agriculture, mining and later manufacturing. [xvi] The conquest of Great Zimbabwe was also known as the invasion of Mashonaland. As pointed out earlier, this invasion was brought about by Rhodes British South African Company (BSAC) in 1890 and was conducted by 200 Settlers under the protection of BSAC policemen. [xvii] There were other regions that could have been annexed however Mashonaland was the favoured at that time. Mashonaland was not only chosen for its natural resources, it was chosen above Matabeleland because of its weak forces. At that time it was easier to target than Matabeleland. [xviii]

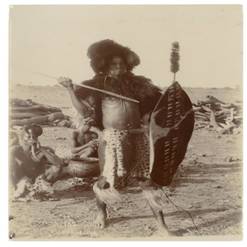

Matabele warrior. Photograph courtesy of Martin Plaut

Matabele warrior. Photograph courtesy of Martin Plaut

Rhodes deceitfully obtained Lippert Concession, which was about the rights to land and minerals granted to Eduardo Lippert from King Lobengula, Rhodes bought the concession from Lippert and then gave BSAC the legal right to obtain large tracts of land from the locals. Land was transferred to white settlers who took part in the occupation of Mashonaland. [xix] After taking over Mashonaland they set up headquarters in Salisbury and began selling off tracks of land. They were met with disappointment when it was discovered that the gold had been exhausted during ancient times. However they were surprised by the quality of the agricultural land and climate. [xx] The BSAC concession did not include ownership of the land as it was limited to mining and this meant that no gold the company would run at a loss. As a result the company sought to extend their right to land ownership and an incident that happened in 1893 made this possible. It was in that year that the Mashona felt emboldened to withhold tribute to Lobengula’s Matabele. Incensed by this Lobengula sent a punitive expedition to get what he regarded as his tribute.” This gave the company the excuse they needed to intervene apparently on humanitarian grounds by fighting for the Mashona. [xxi] Lobengula granted land and mineral rights to a Johannesburg businessman in an effort to weaken Rhodes’ position. However, Rhodes knew about the transaction and bought the concession from Lippert thus strengthening his position.

This was not enough for Rhodes as the lack of Gold in the land did not meet the anticipated profit, and investors showed concern, under pressure from investors Rhodes set his eyes on Matabeleland. This marked the beginning of the 1893 war when Lobengula was defeated. The area was then named Southern Rhodesia. [xxii] The war began as resistance led by King Lobengula to BSCA occupation, but they were no match to BSAC and were crushed by BSAC forces. Consequently the King Lobengula fled north where he spent his last days. [xxiii] The BSAC had the latest military artillery. [xxiv] When King Lobengula died, his Indunas were left with no other choice, but to make peace with company as they did not have the manpower to fight BSAC. Consequently Matabele land was officially added to the BSAC’s territory. [xxv]

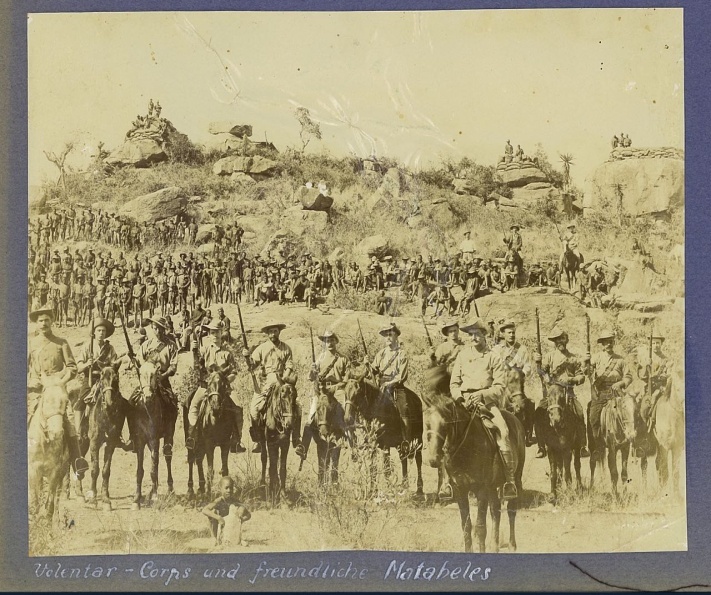

Volunteer Corp and Matabele men. Photograph courtesy of Martin Plaut

Volunteer Corp and Matabele men. Photograph courtesy of Martin Plaut

After taking over Matabeleland, BSAC troops were withdrawn from the area, which opened the opportunity for a second rebellion. In 1896 Matabele religious leaders formed a new kind of leadership who organised the rebellion. [xxvi] Isolated farmers were murdered and communication to Bulawayo was cut off. Without its troops the BSAC could not handle the rebellion and as a result Rhodes had to travel to the area with relief column to rescue European settlers who were under attack. The religious leaders who organised the campaign were tracked down and assassinated by two scouts. Rhodes used this turn of events as an opportunity to negotiate an end to the war. [xxvii]

Rhodes pioneer corps in Rhodesia and its last days

During the first nine years of the BSAC settlement, the area was under the control of a one man government, its first administrator being Mr AR Colquhoun, who later resigned and was succeeded by Leander Starr Jameson. [xxviii] Leander Starr Jameson was given the role of administrator and assumed the right to distribute the wealth of the Ndebele people. The land was distributed to the military and the ‘honorables’ in lavish quantities while the Ndebele people were relegated to limited reserve space in areas that were not favoured. Such action contributed to the resentment of white settlers by locals. [xxix]

In 1899 Rhodes’ BSAC formed a Legislative Council with a small number of directly elected seats. The electorate was comprised of white settlers only. The BSAC was becoming unpopular consequently in the early nineteenth century saw the decline of BSAC control over the region. By 1918 most settlers were not happy with the BSAC rule and as more European settlers were arrived the company was losing its support base. Added to the woes of the BSAC were stipulations that offered a measure of protection for ‘Black Africans’, which many European settlers did not support. [xxx] In 1920 the Legislative Council brought back a large number of candidates from the Responsible Government Association: a clear indication that BSAC was losing support of its base. By 1922 the BSAC had lost its power and consequently handed over control over to the settlers. With power on their side the settlers had the liberty of changing the constitution. Unsurprisingly they abandoned legislation that protected ‘Black Africans’ and passed punitive and restrictive laws. These laws were mostly concerned with the distribution of land and they reserved 50 percent of the land for their small community of European settlers. [xxxi]

Although this historical event marked the end of the BSAC’s reign, Rhodes’ memory continued to be honoured as the region’s name was not changed until the overthrowing of this administration by the liberation movement; led by the likes of Robert Mugabe and other respective freedom fighters, following which the country was renamed Zimbabwe.

Endnotes

[i]Royal Pioneer Corps, RLC Archive.org http://www.rlcarchive.org/ContentRPC ↵

[ii]History and background of the Royal Pioneer Corps, The Pioneer http://www.royalpioneercorps.co.uk/rpc/history_main1.htm ↵

[iii]Ibid. ↵

[iv]South African History Online, Cecil John Rhodes http://www.sahistory.org.za/people/cecil-john-rhodes ↵

[v]Cecil Rhodes biography, Encyclopedia of world biography http://www.notablebiographies.com/Pu-Ro/Rhodes-Cecil.html ↵

[vi]Cecil John Rhodes, MSU education http://overcomingapartheid.msu.edu/people.php?id=65-251-109 ↵

[vii]Ibid. ↵

[viii]Ibid. ↵

[ix]Boddy-Evans A, 2017 British South Africa Company, About Educationhttp://africanhistory.about.com/od/glossarybb/g/def-BSAC.htm ↵

[x]Ibid. ↵

[xi] Ibid. ↵

[xii]Ibid. ↵

[xiii]Zimbabwe Embassy, History of Zimbabwe http://www.zimembassy.se/history.html ↵

[xiv]Mlambo A S, 2014, A History of Zimbabwe, University of Pretoria, Cambridge University Press https://books.google.co.za/books?id=0kwHAwAAQBAJ&printsec=frontcover&dq=history+of+zimbabwe&hl=en&sa=X&ved=0ahUKEwiT9--36LTRAhUkBMAKHToGDT0Q6AEIKTAA#v=onepage&q=history%20of%20zimbabwe&f=false ↵

[xv]Mabuse A A, 2013, Settlement history of Bukalanga, Kalanga http://kalanga.org/history/settlement-history/

[xvi]Mlambo A S, 2014, A History of Zimbabwe, University of Pretoria, Cambridge University Press https://books.google.co.za/books?id=0kwHAwAAQBAJ&printsec=frontcover&dq=history+of+zimbabwe&hl=en&sa=X&ved=0ahUKEwiT9--36LTRAhUkBMAKHToGDT0Q6AEIKTAA#v=onepage&q=history%20of%20zimbabwe&f=false ↵

[xvii]Zimbabwe: British South Africa Company rule (1890-1923), 2007 EISA https://eisa.org.za/wep/zimoverview1.htm ↵

[xviii]Ibid. ↵

[xix]British South Africa Company Historical catalogue & souvenir of Rhodesia Empire exhibition, Johannesburg 1936-37, Token coinshttp://www.tokencoins.com/bbp.htm ↵

[xx]Rhodesia brief history, The British Empirehttp://www.britishempire.co.uk/maproom/rhodesia.htm ↵

[xxi] Ibid. ↵

[xxii]Ibid. ↵

[xxiii]Ibid. ↵

[xxiv]Ibid. ↵

[[xxv]British South Africa Company Historical catalogue & souvenir of Rhodesia Empire exhibition, Johannesburg 1936-37, Token coins http://www.tokencoins.com/bbp.htm ↵

[xxvi]Rhodesia brief history, The British Empirehttp://www.britishempire.co.uk/maproom/rhodesia.htm ↵

[xxvii]Ibid. ↵

[xxviii]Southern Rhodesia 1890 – 1950; A record of Sixty years progress https://archive.org/stream/SouthernRhodesia1890-1950ARecordOfSixtyYearsProgress/SR9050_djvu.txt ↵

[xxix]Rhodesia brief history, The British Empirehttp://www.britishempire.co.uk/maproom/rhodesia.htm. ↵

[xxx]Ibid. ↵

[xxxi]Ibid. ↵