The history of the struggle against racial oppression and exclusion in South Africa is inextricably intertwined with the struggle of workers against exploitation. The emergence of trade union activity in the country and subsequent protests against unfair and exploitative labour practices brought workers in direct conflict with the state. A case in point is the 1922 mineworkers strike, in which a number of people died. Another strike which provoked the anger of the government was the 1946 strike. In response to a call made by the African Mine Workers Union (AMWU), over 60 000 workers went on strike at the Witwatersrand Gold Mines on Monday 12 August 1946. The call on 13 August by the Transvaal Council of Non European Trade Union for a general strike of black workers added momentum to the strike. The strike continued until 16 August 1946, resulting in the loss of 183 467 ‘man days’ to various mining companies.

The trial of trade unionists, mineworkers and members of the CPSA

In response to the strike, the government deployed a contingent of 1,600 white police to put down the strike. As a result of confrontations between workers and the police nine people were killed and more than 1,200 injured. In addition, it is estimated that more than 1,000 people were arrested and detained, including leaders of the AMWU. Among those arrested were leading members of the Communist Party of South Africa (CPSA, later renamed the South African Communist Party, SACP), African National Congress (ANC) and the Council of Non European Trade Unions (CNETU). The police also raided CPSA offices in Johannesburg and Cape Town. During the raid in Johannesburg Danie du Plessis, the CPSA’s District Secretary, was arrested.

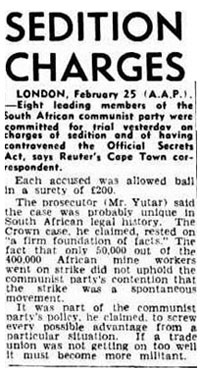

The story of the Sedition Trial was covered by newspapers as far as Australia. An extract of The Courier Mail, 26 February 1946

The story of the Sedition Trial was covered by newspapers as far as Australia. An extract of The Courier Mail, 26 February 1946

A few days later the entire Johannesburg District Committee of the CPSA was arrested. Yusuf Dadoo, who was serving a three-month prison sentence in Newcastle for his role in the passive resistance campaign, was brought from prison and charged again. Dadoo, along with Dr Naicker, vigorously opposed the Ghetto Act which banned land transfers between Indians and non-Indians.

By the time the trial commenced on 26 August 1946, 52 people were charged with sedition under the Riotous Assemblies Act and War Measure 145. The latter piece of legislation which was passed in 1942, banning strikes by Africans and prescribing a punishment of £50 or three years’ imprisonment. It remained in force until the enactment of the Native Labour Disputes Settlement Act of 1953. Its application followed repeated attempts by the government to suppress the trade union movement in the 1940s. Among those brought to trial were volunteers and trade union organisers who had organised the strike. The trial, which became known as the Sedition Trial, was held in Johannesburg and became the biggest political trial in South African history, surpassing the trial of those accused in the 1922 mineworkers’ strike.

During the trial, blame for the strike was placed on the CPSA. The police, officials from the Chamber of Mines and managers of compounds gave evidence. One compound manager working for the New Kleinfontein Mine testified that while African workers were allowed to organise workers, all mines followed a policy of dismissing those who engaged in organising workers. It also became evident that both the Chamber and the government attempted to curtail activities of the AMWU with action against the leadership and membership. For instance, the Chamber persistently pressurised the government to detain the president and secretary of the AMWU, John Beaver (JB) Marks and James Majoro.

After weeks of argument, the court was adjourned to allow prosecutors who offered defence lawyers of a ‘plea bargain’. The state proposed that if the accused pleaded guilty for violating the War Measures, all other charges would be dropped. Subsequently, all the accused, in including Yusuf Dadoo and Bram Fischer, pleaded guilty. Judgment was passed on 4 October 1946. James Majoro, the secretary of the AMWU, and several members of the CPSA were fined £50 or four months of hard labour. Half of this sentence was suspended for a year on condition that they not participate in strikes during that period. The rest of the accused were fined £15 or three months.

Sedition trial of CPSA Central Committee members

However, the state was not content with the outcome. As the proceedings were underway the police on 21 September 1946 simultaneously raided the CPSA’s offices, and private houses of members of the Natal Indian Congress, the Guardian and the Springbok Legion in nine urban centres. Books and documents were seized in the hope that they would uncover incriminating evidence against the leadership of the CPSA. Following the raid, in November all members of the national Central Executive Committee of the CPSA were arrested and charged with sedition and treason. The government continued to apply pressure on the AMWU in an attempt to weaken its influence.

The state prosecutors alleged that the accused had engineered the African mine workers’ strike in August 1946 by encouraging militancy among mine workers in order to gain members and sought to overthrow the government.

Moses Kotane, Secretary General of the SACP was one of the party’s leaders charged with sedition in 1946. Source: Academy of Achievement

Moses Kotane, Secretary General of the SACP was one of the party’s leaders charged with sedition in 1946. Source: Academy of Achievement

In addition, the State also alleged that the accused had violated the Official Secrets Act. Among some of the accused were the party’s Chairman WH Andrews, its Secretary Moses M Kotane, Harold Jack Simons,Isaac Horvitch, Lionel ‘Rusty’ Bernstein, Harry Snitcher (who produced the Strike Bulletin), HA Naidoo, Fred Carneson and Lucas Philips.

The trial commenced in February 1947, with the prosecutors insisting that the strike was not a spontaneous event, but one that was supported by the CPSA leadership. In its response to the charges, the CPSA claimed that the strike was a spontaneous event. In his testimony for the Defence, HJ Simons stated that, for the Communist party, the word ‘revolution’ did not entail violence to overthrow a properly constituted government.

Over the two-year course of the trial, it became clear through the proceedings that the state lacked evidence to back its accusations. Consequently, in May 1948 the case was dismissed as charges were withdrawn by the state.