Related Collections from the Archive

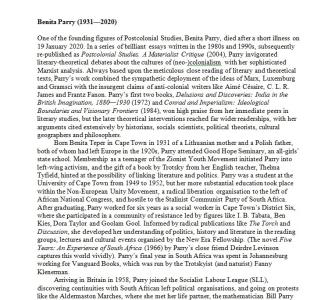

One of the founding figures of Postcolonial Studies, Benita Parry, died after a short illness on 19 January 2020. In a series of brilliant essays written in the 1980s and 1990s, subsequently re-published as Postcolonial Studies. A Materialist Critique (2004), Parry invigorated literary-theoretical debates about the cultures of (neo-)colonialism with her sophisticated Marxist analysis. Always based upon the meticulous close reading of literary and theoretical texts, Parry’s work combined the sympathetic deployment of the ideas of Marx, Luxemburg and Gramsci with the insurgent claims of anti-colonial writers like Aimé Césaire, C. L. R. James and Frantz Fanon. Parry’s first two books, Delusions and Discoveries: India in the British Imagination, 1880—1930 (1972) and Conrad and Imperialism: Ideological Boundaries and Visionary Frontiers (1984), won high praise from her immediate peers in literary studies, but the later theoretical interventions reached far wider readerships, with her arguments cited extensively by historians, socials scientists, political theorists, cultural geographers and philosophers.

Born Benita Teper in Cape Town in 1931 of a Lithuanian mother and a Polish father, both of whom had left Europe in the 1920s, Parry attended Good Hope Seminary, an all-girls’ state school. Membership as a teenager of the Zionist Youth Movement initiated Parry into left-wing activism, and the gift of a book by Trotsky from her English teacher, Thelma Tyfield, hinted at the possibility of linking literature and politics. Parry was a student at the University of Cape Town from 1949 to 1952, but her more substantial education took place within the Non-European Unity Movement, a radical liberation organisation to the left of African National Congress, and hostile to the Stalinist Communist Party of South Africa. After graduating, Parry worked for six years as a social worker in Cape Town’s District Six, where she participated in a community of resistance led by figures like I. B. Tabata, Ben Kies, Dora Taylor and Goolam Gool. Informed by radical publications like The Torch and Discussion, she developed her understanding of politics, history and literature in the reading groups, lectures and cultural events organised by the New Era Fellowship. (The novel Five Years: An Experience of South Africa (1966) by Parry’s close friend Deirdre Levinson captures this world vividly). Parry’s final year in South Africa was spent in Johannesburg working for Vanguard Books, which was run by the Trotskyist (and naturist) Fanny Klenerman.

Arriving in Britain in 1958, Parry joined the Socialist Labour League (SLL), discovering continuities with South African left political organisations, and going on protests like the Aldermaston Marches, where she met her life partner, the mathematician Bill Parry (https://www.theguardian.com/news/2006/oct/13/guardianobituaries.obituaries). Parry left the SLL in 1961, disillusioned by what she later described as her ‘misgivings about hierarchical organisations that “devour souls”’, but she continued for the rest of her life to support both materially and through her writing a number of radical causes, notably the 1983 People’s March for Jobs, the 1984-85 Miners’ Strike, anti-fascist and anti-racist organisations, and the struggle of the Palestinian people.

In the 1960s and 1970s, Parry’s distinctive formation as a literary critic at a distance from the formal rituals of university training continued. In 1962 she returned to academic study, obtaining an MA in History from Birmingham University, but then proceeded independently to transform her MA thesis into her first book, Delusions and Discoveries, which was completed as she raised her young daughter, Rachel. Delusions and Discoveries has been hailed as a major precursor to Edward Said’s Orientalism (1978) and was re-published by Verso in 1998. Her second book on Conrad was also written without access to the usual scholarly networks, but it reached more readers, not least because of a favourable review in the Times Literary Supplement by Said, who praised its originality, describing it as an ‘interesting and suggestive work . . . built around a dense and intelligent analysis’. This exposure led to a trickle of doctoral students establishing contact with Parry, gradually introducing her to a larger community of sympathetic interlocutors.

In the 1980s, as the new academic field of Postcolonial Studies gathered momentum, Parry published her most influential essay, ‘Problems in Current Theories of Colonial Discourse’ in the Oxford Literary Review of 1987. Acknowledging that her personal history and political disposition predisposed her to ‘blunder into disciplinary fields without observing protocols’, Parry scrupulously exposed the evasions and silences of the dominant varieties of postcolonial theory. Looking back more than thirty years later, Parry recalled that she strove in the essay both to critique the ‘professional academics who gave comfort to an iniquitous system, and postcolonial theorists flaunting an ostentatious and vacuous radicalism’, and to affirm ‘the writings of theoreticians who were architects of anti-imperialist struggles’ – Cabral, Machel, Sankara, Lumumba, Mariátegui, Guevara, and many more.

In the early 1990s, Parry acquired her first university affiliation, teaching an MA course in the Department of English and Comparative Literary Studies at Warwick University. This led in time to an honorary chair with the title ‘Professor of Postcolonial Studies’, the supervision of a number of successful PhD students, and key contributions to the Warwick Research Collective, culminating in the book Combined and Uneven Development: Towards a New Theory of World-Literature (2015).

Parry’s legacy is captured in Sharae Deckard and Rashmi Varma’s recent collection, Marxism, Postcolonial Theory and the Future of Critique. Critical Engagements with Benita Parry (2019), which includes a long interview with Parry and her graduation address at the University of York in 2016. In the interview, Parry’s critical edge is much in evidence, as she excoriates revisionist historians and journalists for disparaging ‘revolutionary impulses and energies’, and then proceeds to highlight how influential critical theorists have in recent times sought to diminish the centrality of Marxism to Fanon, Gramsci and Luxemburg. The interview concludes on a utopian note, however, with Parry quoting Ernst Bloch’s conviction that Marxism has driven our dreams further forward and strengthened them with concreteness. In the graduation address, Parry challenged her audience to understand ‘the inflictions visited on the dispossessed and [to protest] against these both as citizens and in our academic work’. Both in the way she lived her life and in her academic work, Benita Parry more than met these dual challenges.

Benita Parry is survived by her daughter Rachel, Rachel’s partner Dave, and her grand-daughters, Sasha and Jessie.

David Johnson