History is not kind to Nongqawuse.

What we know of her is mainly related to the Cattle-Killing/Millenarian Movement of 1856-7 and her role and relations therein. She enters history either through colonial records or the oral traditions passed down from generations amongst the Xhosa people. There is little evidence to discern who she actually was and why she in particular made the prophecies she did, let alone whether the prophecy was true or not. There are only varying perspectives and speculations based on the evidence available.

Nongqawuse is said to have been an orphan and the niece of Mhlakaza. Mhlakaza’s father was the councillor of Chief Sarhili. After Mhlakaza’s mother died, he went to the Cape Colony and became familiar with Christianity. He returned to Xhosaland in 1853. [1] Nongqawuse’s parents died in the battles of the Waterkloof. [2] As a result she is believed to have been quite conscious and aware of the tensions between the Xhosa and the colonial forces. The Xhosa were experiencing an onslaught of attacks upon their community and institutions by British colonial authorities from as early on as 1779. [3] Lungsickness was widespread amongst the cattle of the people. [4] Growing up with her uncle as her guardian, Nongqawuse was influenced by Mhlakaza – a deeply religious man.

Nongqawuse enters into historical records at the age of 15 or 16. She and another young girl aged 8-10 called Nombanda, visited some of the cultivated fields by the Gxarha River to guard the crops and chase away birds. [5] Two strangers appeared to Nongqawuse instructing her to pass on the following ancestral pronouncements, that:

1)the dead would arise;

2)all living cattle would have to be slaughtered, having been reared by contaminated hands;

3)cultivation would cease;

4)new grain would have to be dug;

5)new houses would have to be built;

6)new cattle enclosures would have to be erected;

7)new milk sacks would have to be made;

8)doors would have to be weaved with buka roots and lastly;

9)that people abandon witchcraft, incest and adultery. [6]

Nongqawuse reported these instructions to Mhlakaza, who subsequenty informed the royal officials. Despite their initial reservations, these officials came to visit Mhlakaza’s homestead and the Gxarha River with Nongqawuse, and eventually they were convinced. [7] From then onwards, Nongqawuse’s role was mainly to be the medium of communication between the ancestors and the people. Mhlakaza was the interpreter and organizer of her prophecies and visions. [8] There is no account of Nongqawuse words; only what others observed and experienced of her during this period.

There is, for instance, this description by a police informant:

A girl of about 16 years of age, has a silly look, and appeared to me as if she was not right in her mind. She was not besmeared with clay, nor did she seem to me to take any pains with her appearance. [9]

A record of Nongqawuse’s interrogation by Major Gawler at Fort Murray, which is not deemed as one hundred percent reliable:

Major Gawler: Do you know Nombanda who lived near your kraal, and if so state all you know about her?

Nongqawuse: Nombanda was sent for by the chiefs to bear witness to what I was saying, afterwards when I got ill she used to conduct the talking. She talked a great deal more than I did – the first day she went with me she could neither see the people nor hear them talk. [10]

A description by Mjuza who led a police arrest for Nombanda, who had lent a helping hand in communicating with visitors who came to Mhlakaza’s homestead to see Nongqawuse and hear of the prophecy:

One of Umhlakaza’s prophetesses, and one who spoke equally as much as, and was frequently preferred to [Nongqawuse], - and better liked by the chiefs. [11]

A statement by Nombanda:

I frequently accompanied Nonqause to a certain bush where she spoke with people – and although she frequently informed me when I was with her at this bush, that she saw people and heard them speak to her – I neither saw them nor did I hear them speak till after I had constantly visited the bush with her. [12]

Not everyone believed Nongqawuse. The Chief Ngubo went to Gxarha to confront her:

[Nongqawuse] went to the place, and said they refused to see him [Ngubo] as he had not killed his cattle or destroyed his corn … This did not satisfy him, so he went to the place and said that he insisted on seeing them and talking to them himself. The girl told him he would die if he did, on which he beat her and called her an impostor. [13]

Believers of Nongqawuse’s prophecies followed the instructions of her prophesy, slaughtering their cattle and living in near starvation. However, when the promises failed to materialise, pressure began to mount on both her and Mhlakaza to account for why the prophesies remained unfulfilled. [14] Mhlakaza made various excuses, but eventually people began to lose faith that the prophesy would come to fruition. Unfortunately, the Xhosa had already destroyed most of their crops and their cattle and starvation had set in. It was easier now for the colonial authorities to swoop in and coerce the Xhosa into subordination.

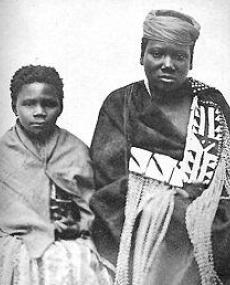

As for Nongqawuse, the chief of Bomvana handed her over to Major Gawler and she stayed at his home for a period. [15] One day Mrs Gawler decided to dress her, along with the Mpongo prophetess Nonkosi, and have their portrait taken by a photographer. [16] This is the widely circulated image of Nongqawuse with which most people are familiar.

In October 1858 Nongqawuse travelled to Cape Town abroad the Alice Smith. [17] She and Nonkosi were taken to the Paupers’ Lodge as prisoners. [18] After that there is no official mention of Nongqawuse. When the Paupers’ Lodge was broken up in August 1859 her name was not on the list of prisoners. [19] There was a ‘Notaki’, who could possibly have been Nongqawuse or Nonkosi. [20] But, it is only one of them that returned with the other female prisoners to East London. Since that time only tentative traces of Nongqawuse exist:

- Sir Walter Stanford said she was living on a farm in Alexandria near Port Elizabeth in 1905.

- A settler historian by the name of Cory was informed that she was alive in 1910 under the name of Victoria Regina, but he did not find her.

- In 1938, the journalist DR d’Ewes claimed to have traced her in Alexandria, where two elders in the neighbourhood told him that she had settled on a farm, was married and had two daughters.

- She is rumoured to be buried on the farm of Glenthorn near Alexandria with her two daughters. [21]

- he writer of The Dead Will Arise, Jeff Peires says he visited Alexandria and was introduced to Nongqawuse’s great-niece and great-nephew. [22]

Given the massive ramifications of her prophesy, there are a number of competing perspectives, which seek to understand who Nongqawuse truly was and the nature of her visions. Whatever perspective one chooses to sympathise with most, one must recognise that any view of her must reckon with a particular interpretation of her visions, which were not unique amongst the Xhosa.

One huge point of contention about Nongwawuse is whether she was an autonomous woman or an innocent child manipulated by her uncle – which is the theory propagated by the scholars Helen Bradford and Jeff Peires. Peires understands Nongqawuse in light of the fact that she was a child that had not yet hit puberty. [23] The ancestors contacted her for her very purity but she did not have the authority to spread the word hence the ancestors told her to communicate with Mhlakaza who was to inform the chiefs. [24]

Bradford makes her assessment of Nongqawuse from the point of view of gender analysis, treating Nongqawuse as an active agent in the whole saga. She considers that Nongqawuse may have been a victim of incest, orphaned by her parents specifically due to colonial conflict, and raised by her religious guardian. [25] With this in mind, Bradford gives attention to the significance of the cecessation of cultivation, which was deemed women’s work, and the appeal to stop witchcraft, adultry and incest. [26] Bradford suggests that Nongqawuse was actively condemning immorality in her society, drawing upon ancestry and prophecy to authorise her declarations. [27]

Then there is the image of Nongqawuse as a villain or foolish girl in Xhosa oral traditions. She is considered to have betrayed her people and caused the downfall of the Xhosa nation. Some go as far as believing that she was manipulated by the colonial authorities, who, it is speculated, had dressed up as ancestors in order to trick her. The excerpts from Xhosa poems below are illustrative of the sense of betrayal that some Xhosa people felt following the failure of Nongqawuse’s prophesy to materialise:

Hayi uNongqawuse

Intombi kaMhlakaza

Wasibulala isizwe sethu

Yaxelela abantu yathi kubo bonke

Baya kuvuka abantu basemangcwabeni

Bazisa uvuyo kunye ubutyebi

Kanti uthetha ubuxoki [28]

Oh! Nongqawuse!

The girl of Mhlakaza

She killed our nation

She told the people, she told them all

That the dead will arise from their graves

Bringing joy and bringing wealth

But she was telling a lie

Kulo mhla ke lehl’ inyala,

Kuba yem’ intombi kaMhlakaza,

Iba ngakuvela phezu komlambo,

Ibuy’ ingxak’ iyiphethe ngomlomo,

Ibikel’ amadoda.

Int’ ezingazanga zeva ngedikazi.

Yayilishobo kwaloo nto,

Ukuqalekiswa kwesizwe sikaXhosa,

Kusuk’ umntw’ ebhinqile

Ath’ uthethile namanyange…

Nalishoba kuloo nzwakazi,

Intomb’ emabele made:

Kuloko loo min’ ayezizibhungu,

Kub’ intombi yayiqal’ ukuz’ ebuntombini.

Yathi kanti noko kunjalo

Ishoba lokubulal’ umzi kaPhal’ ungenatyala

Liya kungena ngayo [29]

On this day, then, indecency descended,

For the maiden of Scatterer stood up,

She even appeared on the river bank,

She returned carrying the problem in her mouth,

She reported to men.

Those who have never been told what to do by a promiscuous woman.

That in itself was an omen,

A curse upon the nation of Xhosa,

A female gets up

Saying she spoke with the ancestors…

There is an omen in that handsome woman,

The maiden with pendulous breasts:

Except on that day when they were large and protuberant,

Because a marriageable maiden had begun to emerge from maidenhood

And yet even if it were so

The omen killing the innocent nation of Phalo

Will enter through her.

In conclusion, Nongqawuse’s true identity before she saw the two strangers by the Gxarha River remains unknown. We do not know if she was truly a prophet, or a girl who imagined things and was used by her uncle, or if she was simply tricked. We do not know for certain if she was an independent agent condemning her society for its moral decay or if she sold out her people to the colonial authorities. However, what seems certain is that history has traditionally been quite unkind to her, relegating her existence to that of culprit, solely responsible for the downfall of the Xhosa nation.

Endnotes

[1] Jeff Peires, The Dead Will Arise: Nongqawuse and the Great Xhosa Cattle-Killing of 1856-7 (Johannesburg and Cape Town: Jonathan Ball Publishers, 2003), 327. ↵

[2] Ibid, 328. ↵

[3] Ibid, 331. ↵

[4] Ibid, 330. ↵

[5] Ibid, 99. ↵

[6] Ibid ↵

[7] Ibid, 101. ↵

[8] Ibid, 369. ↵

[9] Ibid, 363. ↵

[10] Ibid ↵

[11] Ibid ↵

[12] Ibid, 112. ↵

[13] Ibid, 115. ↵

[14] Ibid, 165-180. ↵

[15] Ibid, 355. ↵

[16] Ibid ↵

[17] Ibid, 356. ↵

[18] Ibid ↵

[19] Ibid ↵

[20] Ibid ↵

[21] Ibid ↵

[22] Ibid ↵

[23] Ibid, 367. ↵

[24] Ibid, 369. ↵

[25] Helen Bradford, “Women, Gender and Colonialism: Rethinking the History of the British Cape Colony and Its Frontier Zones, C. 1806-70”, The Journal of African History Volume 37, Issue 3 (1996): 365 ↵

[26] Ibid, 361. ↵

[27] Ibid, 363. ↵

[28] Jeff Peires, The Dead Will Arise: Nongqawuse and the Great Xhosa Cattle-Killing of 1856-7 (Johannesburg and Cape Town: Jonathan Ball Publishers, 2003), 21. ↵

[29] Helen Bradford, “Not a Nongqawuse Story: An anti-heroine in historical perspective” in Nomboniso Gasa (ed.), Women in South African History: They Remove Boulders and Cross Rivers (Cape Town: HSRC Press, 2007), 47-48. ↵