The 1956 Women’s March in Pretoria, South Africa constitutes an especially noteworthy moment in women’s history. On 9 August 1956, thousands of South Africa women – ranging from all backgrounds and cultures including Indians, Coloureds, Whites, and Blacks – staged a march on the Union Buildings of Pretoria to protest against the abusive pass laws. Estimates of over 20,000 women – some carrying young children on their backs, some wearing traditional dresses and sarees, and others clothed in their domestic work outfits – all showed up to take part in the resistance against apartheid. The 1956 Women’s March played a vital role in the women becoming more visible participants in the anti-apartheid struggle.

Origin of the Women’s Movement Against Pass Laws

In South Africa, pass laws were a form of an internal passport system designed to segregate the population between Blacks from Whites in South African, and thereby, severely limit the movements of the black African populace, manage urbanization, and allot migrant labor. As early as 1893, pass laws originated in the capital of the Orange Free State of South Africa, Bloemfontein, requiring non-white women and men to carry documentation to validate their whereabouts. Pass laws were a means of trying to control South Africans of getting into the city, finding better work, and establishing themselves in the “white” part of town, which of course was desirable on account of employment opportunities and transportation. If non-Whites sought to enter the restricted areas destitute of their passes, they suffered imprisonment and worse. However, in the location of Waaihoek black people drew up a petition which they submitted to the Town Council complaining about the harshness of the laws passed to control them. While the council responded to some of their requests, the one requiring women to carry residential passes remained. On 2 October 1898, women were so frustrated by the carrying of passes that a number of them in the location drew up a petition to President Marthinus Theunis Steyn protesting against being made to carry passes.

In 1906 the government published new rules for the enforcing the passes and police were given instructions of how to enforce the regulations. By October 1906 the effects of enforcing the residential pass were being felt in Waaihoek. White farmers also pushed for more stringent measures to control black people. As a result a new pass law aimed at black in rural areas was put in force. Residents continued to protest against the new regulations by appealing to the government. They also wrote to the African People’s Organisation (APO), a political organisation representing Coloured people. In response, APO complained in March 1906 about the cruel way in which the government treated women who were found without passes. It highlighted how women were taken away from their families if authorities felt they had broken laws that forced them to carry passes. However, the government moved to pass more laws forcing more people to carry passes. For example, in 1907 a new law was passed in Bloemfontein requiring domestic servants to carry a Service book where details on their employment were written. These books were to be carried at all times and produced when demanded. Any person found without the book more than three times could be taken away from the municipality where they lived. In 1908 a special Native Administration commission was established to investigate labour needs. It recommended the passing of even stricter pass laws and that families in rural areas should be automatically made servants.

When the Union of South Africa was established in 1910, there was already a foundation for pass system. However, over time men and women resisted the imposition of passes as it severely restricted their freedom. Black women who had borne the brunt of the pass laws decided to act. Drawing inspiration from the first meeting of the South African Natives National Congress (SANNC) in their town in February 1912, they sent around a petition to towns and villages in the Orange Free State. In March, the Minister of Native Affairs, Henry Burton wrote to John Dube the President of the SANNC, telling him not to send a delegation of women to Cape Town to meet with him (Wells, 1983). The minister claimed that the issue women were raising was a problem of the Orange Free State. But greatest fear was that the protest would ignite countrywide protests by black people given that the mobilisation of the women collected five thousand signatures in protest against the passes that they had to carry. A delegation of six women presented their case to the Minister of Native Affairs, responded that in the future “he would take action to eliminate pass regulations” (Wells, 1983). In March 1912, a petition signed by some 5 000 Black and Coloured women in the Free State, was sent to Prime Minister Louis Botha asking for the repeal of the pass laws. There was no response.

A year later when no changes were made, women found their frustrations growing as the government continued to ignore their demands. On 3 April 1913 a delegation of six women together with Walter Rubusana met the Minister of Native Affairs. Among the women were Mrs. A. S. Gabashane, Mrs. Kotsi and Katie Louw. They submitted a petition of over 5000 signatures and the government promised to look into their complaint. In the petition women stated that the pass laws and other regulations “lower the dignity of women and throws to pieces every element of respect to which they are entitled...” They further complained that the laws were designed to make women feel inferior. Newspaper headlines in the Orange Free State called women who were protesting “Women Terrorists”. On 29 March 1913, women “pledged to refuse to carry passes any longer and expressed their willingness to endure imprisonment”. The escalation of pass laws continued and triggered growing irritation.

In 1913 a group of women led by Charlotte Maxeke burned their passes in front of municipal offices, staged protest marches, sang slogans and fought with the police. Many women were arrested in Jagersfontein, Winburg and Bloemfontein. In May 1913, the police arrested large numbers of men and women for pass laws violations throughout the Orange Free State. This came after brief period of where the enforcement of pass laws seemed to have been relaxed in the province. The number of women was particularly high in Bloemfontein with four times higher than the previous month. Georgina Taaibosch an outspoken woman who refused to submit to oppression was arrested for the first time. In other parts of the province such as Winburg two women were charged in May while in Jagersfontein eight women were arrested.

Following these arrests, black African women convened a meeting in Waaihoek where they talked about their anger at the government for their harassment. They resolved not carry passes if the government did not relax the existing laws and order the police to show maturity in treating women. From there a group of 200 women marched into town demanding to see the mayor. When they did not find him they sent a delegation to meet him the following day. The mayor told them there was nothing that he could do about their plight.

Women did not become discouraged; they took their fight to the local police station where they protested. They tore their passes and threw them to the ground preferring to be arrested than suffer indignity. As a result, 80 women were arrested and charged for violating pass laws. This sparked an even bigger demonstration the following day. A crowd of about 600 women headed by Mrs Molisapoli marched and chanted slogans towards the magistrates court where their comrades were being tried. When the police attempted to keep them off the steps of the court a violent rebellion nearly broke out.

In June 1913, a group of between 200 and 800 women gathered on the City Hall and told the Mayor that they would no longer carry passes. The government began arresting women in large numbers and by July women sent a petition to the Mayor to negotiate abolishing passes for girls over the age of 16 and unmarried women. In addition to protests and petitions, women organised themselves and formed the Orange Free State Native and Coloured Women’s Association in Bloemfontein. The organisation was led by Catharina Symmons and Katie Louw. The association raised funds to assist those women who were in jail, and to pay for their medical bills. Between September and October 1913, the Orange Free State women’s Anti-pass Campaign began spreading to other parts of the country, something which the government feared.

Despite pressure applied by the women against pass laws in 1913, the government refused to remove them. Thus, women continued in the following years to apply pressure on the government yielding a positive result. On 27 January 1914 the Executive Committee of the Orange Free State Native and Coloured Women's Association sent a petition to Governor General Gladstone. Women pleaded with him to persuade the Prime Minister and Minister of Native Affairs to relax the pass laws.

As a result on 3 March 1914 the Prime Minister proposed that all pass laws should be looked into. Members of Parliament from the Orange Free State supported a strict enforcing of the pass laws while some from the Cape disagreed. The Women’s petition was tabled for discussion in parliament on 29 May 1914. However, by mid 1914 the campaign began to lose momentum and eventually ended. The SANNC and APO took up the issue of passes against women in the subsequent years.

In 1918, the government threatened to re-introduce pass laws for women in the Free State and other areas as well. After the formation of the Bantu Women’s League in 1918, Charlotte Maxeke led a delegation to the Prime Minister's office, again, protesting the issue of passes, low wages and other grievances. Hence, civil disobedience and demonstrations continued sporadically for several years. Ultimately the permit requirement was withdrawn. No further attempts were made to require permits or passes for African women until the 1950s. Although laws requiring such documents were enacted in 1952, the Government did not begin issuing permits to women until 1954 and reference books until 1956, and was one of the main components of the women's struggle.

In 1952 the Native Laws Amendment Act tightened influx control, making it an offence for any African (including women) to be in any urban area for more than 72 hours unless in possession of the necessary documentation. The only women who could live legally in the townships were the wives and unmarried daughters of the African men who were eligible for permanent residence. In the same year the Natives Abolition of Passes and Coordination of Documents Act was passed. In terms of this act the many different documents African men had been required to carry were replaced by a single one - the reference book - which gave details of the holder's identity, employment, place of legal residence, payment of taxes, and, if applicable, permission to be in the urban areas. The act further stipulated that African women, at an unspecified date in the near future, would for the first time be required to carry reference books. Women were enraged by this direct threat to their freedom of movement and their anti-pass campaign.

The Women’s Movement in Action

Protests started as early as 1950 when rumours of the new legislation were leaked in the press. Meetings and demonstrations were held in a number of centres including Langa, Uitenhage, East London, Cape Town and Pietermaritzburg. In the Durban protests in March 1950, Bertha Mkize of the African National Congress Womens League (ANCWL) was a leading figure, while in Port Elizabeth Florence Matomela (the provincial president of the ANCWL) led a demonstration in which passes were burnt. By 1953 there were still sporadic demonstrations taking place and these accelerated when local officials began to enforce the new pass regulations. Reaction was swift and hostile. On 4 January 1953, hundreds of African men and women assembled in the Langa township to protest against the new laws. Delivering a fiery speech to the crowd Dora Tamana, a member of the ANCWL and later a member of the Federation of South African Women (FSAW), declared:

We women will never carry these passes. This is something that touches my heart. I appeal to you young Africans to come forward and fight. These passes make the road even narrower for us. We have seen unemployment, lack of accommodation and families broken because of passes. We have seen it with our men. Who will look after our children when we go to jail for a small technical offence - not having a pass

FSAW was launched on 17 April 1954 in the Trades Hall in Johannesburg, and was the first attempt to establish a national, broad-based women's organisation. This was the brainchild of Ray Simons who drew in others such as Helen Joseph, Lillian Ngoyi and Amina Cachalia who formed the steering committee for the organisation. One hundred and forty-six delegates, representing 230,000 women from all parts of South Africa, attended the founding conference and pledged their support for the broadly-based objectives of the Congress Alliance. The specific aims of FSAW were to bring the women of South Africa together to secure full equality of opportunity for all women, regardless of race, colour or creed, as well as to remove their social, legal and economic disabilities.

Furthermore, the "Women`s Charter", written at the first conference in Johannesburg on 17 April 1954, called for the enfranchisement of men and women of all races; equality of opportunity in employment; equal pay for equal work; equal rights in relation to property, marriage and children; and the removal of all laws and customs that denied women such equality. The Charter further demanded paid maternity leave, childcare for working mothers, and free and compulsory education for all South African children. The demands laid out in the "Women`s Charter" were ultimately incorporated into the Freedom Charter, adopted by the Congress of the People in Kliptown on June 25-26, 1955.

A major task of the Federation in succeeding years was the organisation of massive protests against the extension of pass laws to women. Together with the ANCWL, the Federation organised scores of demonstrations outside Government offices in towns and cities around the country. The first national protest took place on October 27, 1955, when 2,000 women of all races marched on the Union Buildings in Pretoria, planning to meet with the Cabinet ministers responsible for the administration of apartheid laws. Ida Mntwana led the march and the marchers were mainly African women form the Johannesburg region. The Minister of Native Affairs, Dr. Hendrik Verwoerd, under whose jurisdiction the pass laws fell, pointedly refused to receive a multiracial delegation.

In 1955, government officials in the Orange Free State declared that women living in the urban townships would be required to buy new entry permits each month. In response to the government’s request, South African women decided to petition and create a document of their values in “The Demand of the Women of South Africa for the Withdrawal of Passes for Women and the Repeal of the Pass Laws," a document which was presented to the Prime Minister. It demanded that the government terminate pass laws. Unified they stood in saying “once the women have made up their minds that they will do it, the women will organize and fight, and you will never stop them.” (Brooks, 225) The petition exemplified their frustration with the government. They were tired of seeing their families “suffering under the bitterest law of all - the pass law which has brought untold suffering to every African family.” (ANC) The petition clearly exemplified their indignation towards the government’s stance on pass laws. Women were tired of the government insisting that the pass laws were abolished, but it is the wives, mothers, and “women that know this is not true, for [their] husbands, [their] brothers, and [their] sons are still being arrested, thousands every day, under these very pass laws.” (ANC) During that time “the husband would come to the house and tell his wife, “I’m going to jail now.” And then the wife says, “Well, I’m going to jail too.” (Brooks, 207) Their formidable courage exhibited the absence of gender roles in the sense of dominating activist ideals.

Previously, men would often voice the opinions of the household, willing to take the consequences, but with the rise and works of the 1956 Women’s March, women were eager and ready for every and any repercussions. And perhaps in retrospect, the rise to political prominence of women was inevitable given that they arguably possessed acute senses as to the destructive repercussions that the pass laws imposed upon families. Women thoroughly comprehended the destruction and detrimental services that the pass laws served within the dynamics of the family setting. The women of South Africa started to realize the tearing away of their family due to the pass laws: it was confining the man, inherent to embrace freedom in his own land, while also destroying the gentle aura, yet protective presence of the motherly woman. With the addition of pass laws, the typical person could not feel as if they were truly inhibiting their character when pushed amongst a wall of confinement and complete control, of course mixed with the ever-so-present ubiquity of apartheid.

In laying out what the pass laws meant to them, the women of South Africa further explained “that homes will be broken up when women are arrested under pass laws.” (ANC) With their frustrations high and their immense dedication, the women of South Africa promised that they “shall not rest until ALL pass laws and all forms of permits restricting our freedom have been abolished” and “shall not rest until we have won for our children their fundamental rights of freedom, justice, and security.” (ANC) The immense amount of passion and determination to make a change is what brought these women together to make history and show the important role of women engaging in activism. These activists “were a big force,” and according to Dorothy Masenya, one of the many women who participated in the 1956 March, no one could stop them – “if they arrest one we all walk in [to jail] and no turning back.” (SAHO-women’s interviews) The women realized that there is strength and power in numbers; that together they can make a difference, and that the government might struggle to stop a unit. The participants accepted significant risks such as arrest or imprisonment, in order to pursue their goal.

Their unified determination established their role in the anti-resistance movement with their use of media, particularly in songs and in photographs. The photograph “Women’s March”, taken by Peter Magubane the day of the march, clearly depicts the unification and strength of women across the country. Several women have their right arm raised high with a clenched fist, a common symbol of power. Whilst marching, the women of the 1956 march sang the now infamous ‘Wathint’ abafazi Strijdom, wathint’ imbokodo, uza kufa”, translated, “you strike the women Strijdom you strike a rock, you will be crushed, you will die” The song was repeatedly sang and dispersed as their freedom anthem amongst the city, in hopes it would echo across the country. The amalgam of women further exhibits the unifying ideals of the feminist empowerment and movement distributed through South Africa in hopes of diminishing pass laws.

Influential Actors in the Conception of the 1956 Women’s March

The march also made several female leaders visible in the struggle against apartheid, particularly Lilian Ngoyi and Helen Joseph. There cannot be change and reconstruction without leaders who are willing to run risks, making a lasting effect. Leaders such as Lilian Ngoyi and Helen Joseph were essential to the brainstorming, organization, and execution of the remarkable event of the 1956 Women’s March. Rahima Moosa, Lilian Ngoyi, Helen Joseph and Sophia Williams led the 1956 Women’s March to the Union Buildings in Pretoria, carrying stacks of petitions to present to the government.

In the beginning stages, Lillian Ngoyi “went around addressing meetings and rallies all over the country; she called on women to be in the forefront of the struggle, in order to secure a better future for [their] children.” (Brooks, 206) Lillian Ngoyi joined the African National Congress (ANC) in 1952, along with political pioneers Kate Mxaktho, Ida Mtwana and Charlotte Mxeke, who co-founded the Women’s League within the ANC. Ngyoi advised that“only direct mass action will deter the Government and stop it from proceeding with its cruel laws.” (Brooks, 223) With that being said, Lilian Ngoyi, as well as other influential leaders, led 20,000 women to protest the inclusion of women in the pass laws controlling the movements of blacks. Holding thousands of petitions in one hand, Lilian Ngoyi personally knocked on Prime Minister J.G. Strijdom’s door to give him the petitions. Lilian Ngoyi did not stop her work in Africa, she soon realized and “recognized the potential influence that international support could have on the struggle against apartheid and the emancipation of black women.” (Grant) Lilian realized that she needed global support from women of diverse backgrounds in order to strengthen freedom and democracy in South Africa. As the National Chairman of FSAW, Ngoyi questioned her audience as to why they “have heard of men shaking in their trousers, but who ever heard of a woman shaking in her skirt?” at the inaugural conference (Grant). Ngoyi’s several positions in leadership have led her to be one of the strongest, black women in politics of South Africa. Because of her great efforts and intense involvement with the ANC and the liberation movement, Ngoyi was arrested and tried for treason; despite that, she remained outspoken on issues regarding Africans and women.

Another influential woman was Helen Joseph, a white anti-apartheid activist. Though there were few white activist against apartheid, Helen Joseph believed that they “shall not rest until the pass laws and all forms of permits restricting our freedom has been abolished.” (Joseph, 1) Helen Joseph, though a white woman, believed it was intolerant to watch the suffrage and separation of South Africa due to pass laws. As part of the Women’s League in the African National Congress she noted that, “she was not a woman doing things for black people but a member of a mixed committee headed by lack women.” (Joseph, 5) Helen Joseph’s values were those of justice and fair treatment, race or color was not a factor in her involvement to a better South Africa. When joining the movement, she “looked at those many faces until they became only one face, the face of suffering black people.” (Joseph, 5) The images of those whose land and freedom have been taken away from them inspired Joseph to make a difference.

The Broader Significance of the 1956 Women’s March

The legacies of the 1956 Women’s March include the rise of several strong female leaders, now visible in the greater struggle against apartheid, as well as the presence of women in mass media that called upon the march to inspire others. Helen Joseph mentions that “it is a story that continues every day.” The women of South Africa joined in forces all for one cause, showing the immense amount of unification and influence that women have in wanting to make a vital change in the entire continent. Several different groups inclined toward fostering women’s empowerment about within the same time period as the initiation of women’s involvement in resistance politics.

Without the force of frustrated and determined women, South Africa’s anti-apartheid resistance may not have been abolished without the assistance of women. During the march, the women sang “wathint' abafazi, wathint' imbokodo,uza kufa! – translating that [when] you strike the women, you strike a rock, you will be crushed [you will die]! (AfricanOnline) The phrase is “so powerful that it has locked into our minds.” (Miller) It is constantly repeated to remind the historic moment when “woman managed to create a public voice for themselves.” (Miller). The song represented their courage, strength, and confidence that there will be changes and an end to the pass laws. The song is still recalled today, over the several years after the abandonment of pass laws. South Africans continue to remember the song in tribute of the power that women had. They constantly refer to themselves as a rock to symbolize themselves as a weapon to be feared.

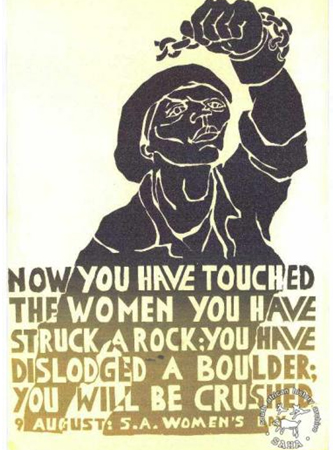

Additionally, one of the most common images of this movement was reproduced in posters such as that shown below, entitled: “Now that you have touched the women, you have a struck a rock, you have dislodged a boulder, you will be crushed.” The poster was re-created by Judy Seidman, an artist in the Medu Art Ensemble in Botswana, South Africa. Dated in 1981, the poster shows that even after 25 years, the march was still being called upon. The poster shows a black woman with a strong, stout face raising her right arm, which has a broken chain on her wrist.

Picture Source: www.saha.org.za

Picture Source: www.saha.org.za

Seidman's poster reflects the strength, tenacity, and frustration that the South African woman faced, clearly seen by the expressions on her face. The image shows the revelation and freedom that women commanded in order to repeal the pass laws. In some cases, the women further established that “once you have touched the women, you are going to die” further establishing their prevalence in the means of the death of the pass laws (Brooks, 204). The poster highlighted the anthem of the anti-apartheid women struggle. When women come together for a bigger cause, a cause that affects their very kin and being, they find strength within each other to further push them towards the goal. In an era when black women did not and –in some cases, could not have a voice, the woman of South Africa shouted, screamed, and yelled in order to get what they rightly deserved, freedom. The involvement of women in activist pursuits has become an authoritative historical point.

In 1998, the Department of Arts, Culture, Science, and Technology (DASCT), created the monument of the Women of South Africa. The monument “allows the voices of the past to an ever present reminder of the power of women.” (Miller, 305). The monument strongly represented women’s political activism and empowerment in times of struggle. On several cases, women see the monument as a “claim for women in centre of political power,” as well as a “visual reminder of how women once asserted themselves here, crowding their bodies in to the otherwise masculine space” (Miller, 310). Men were overshadowed by the strong, dominant presence of the colossal and impactful movement that the women embraced. The feminist site acts as a remembrance, a memoir to the women of South Africa – their struggles their fights, but mostly their voice, without their voice there would be nothing to remember. The walk of 1956 was one of the introductory steps to the feminist movement in South Africa; it laid the groundwork, the outline and the works in order of South Africa to be where it is in current day.

The significance of this march still reigns today in South Africa’s annual celebration of National Women’s Day in regards and respect to that very day on August 9th 1956. The peacefully aggressive nature characterized the women’s march: they did not stop until pass laws were repealed, but they never used violence to progress in their movement. This event illustrated the strength, determination and power that women possess when come across a situation that puts fear of the wellbeing of their children’s future and their kin. In an era where women’s voices were not always heard, the women of South Africa demanded attention for their freedom.

This article was written by Idara Akpan and forms part of the SAHO and Southern Methodist University partnership project