In May 1963, the Cape Times announced the launch of ‘a national art exhibition, open to South African artists of all races’. The first iteration of Art South Africa Today was held at the Durban Art Gallery before touring the country, and its judges included Michaelis School of Fine Art lecturer Maurice van Essche, president of the South Africa Council of Arts Cecil Skotnes, Amadlozi Group artist Giuseppe Cattaneo and Polly Street artist (later a professor of music) Khabi Mngoma.

A total of seven Art SA Today exhibitions took place biennially, from 1963 to 1975. The exhibitions followed other integrated showings, including the 1960 Lawrence Adler Galleries competition and the 1961 Festival Gallery’s Art in Africa Today. Other national exhibitions in the 1950s, ’60s and ’70s had included the works of one or two Black artists, but had not appointed Black jurors or spotlighted overtly political work. The involvement of the South African Institute of Race Relations in organising the Art SA Today exhibitions, along with the Durban Art Gallery and the Natal branch of the South African Association of Arts, further differentiated the shows from most other art events of the period. In 1973, the promotional announcement inviting artists to submit their entries for selection called the exhibition ‘the only one of its kind in South Africa’.

The second Art SA Today exhibition, in 1965, attracted a racially diverse crowd of about 1 000 people to the Durban Art Gallery opening. Judges curated a collection of paintings, graphic art, sculpture and ceramics, and bestowed awards to a broad cross-section of participants. Lawrence Scully and Alison Kelleher won Oppenheimer prizes, Cambridge Shirt awards went to Bill Ainslie and Zainab Reddy, Michael Zondi received the Philip Frame prize and Omar Badsha won the Sir Basil Schonland young artist award.

The exterior of the Durban Art Gallery today. Source: durban.cityseekr.com

The exterior of the Durban Art Gallery today. Source: durban.cityseekr.com

Durban mayor and arts patron Vernon Shearer specified his perspective on the larger social implications of the show in his opening address: ‘This exhibition is an important contribution in the field of race relations for it provides a further opportunity of seeing work of all those who are so gifted, thereby creating a better understanding and appreciation of each other's culture.’

In 1967, judges Carl Buchner, Ronald Lewcock and Eduardo Villa selected 63 works from 400 submissions. Award winners included Ezrom Legae, Bill Ainslie, Sidney Goldblatt and Wiseman Mbambo, with special mention given to Joan Clare, Eric Ngcomo and Herman van Nazareth, among others.

Judges at the 1969 exhibition included art critic Neville Dubow and artist-professor Heather Martienssen, with prizes given to Omar Badsha, Sylvester Mubayi, Louis Maqhubela, Harold Rubin, Andrew Verster and others. The inclusion of works by politically engaged artists such as Badsha, Rubin, Paul Stopforth and Gavin Younge indicated a degree of openness toward socially critical work, though expressions of political resistance remained mostly indirect, abstract and generalised.

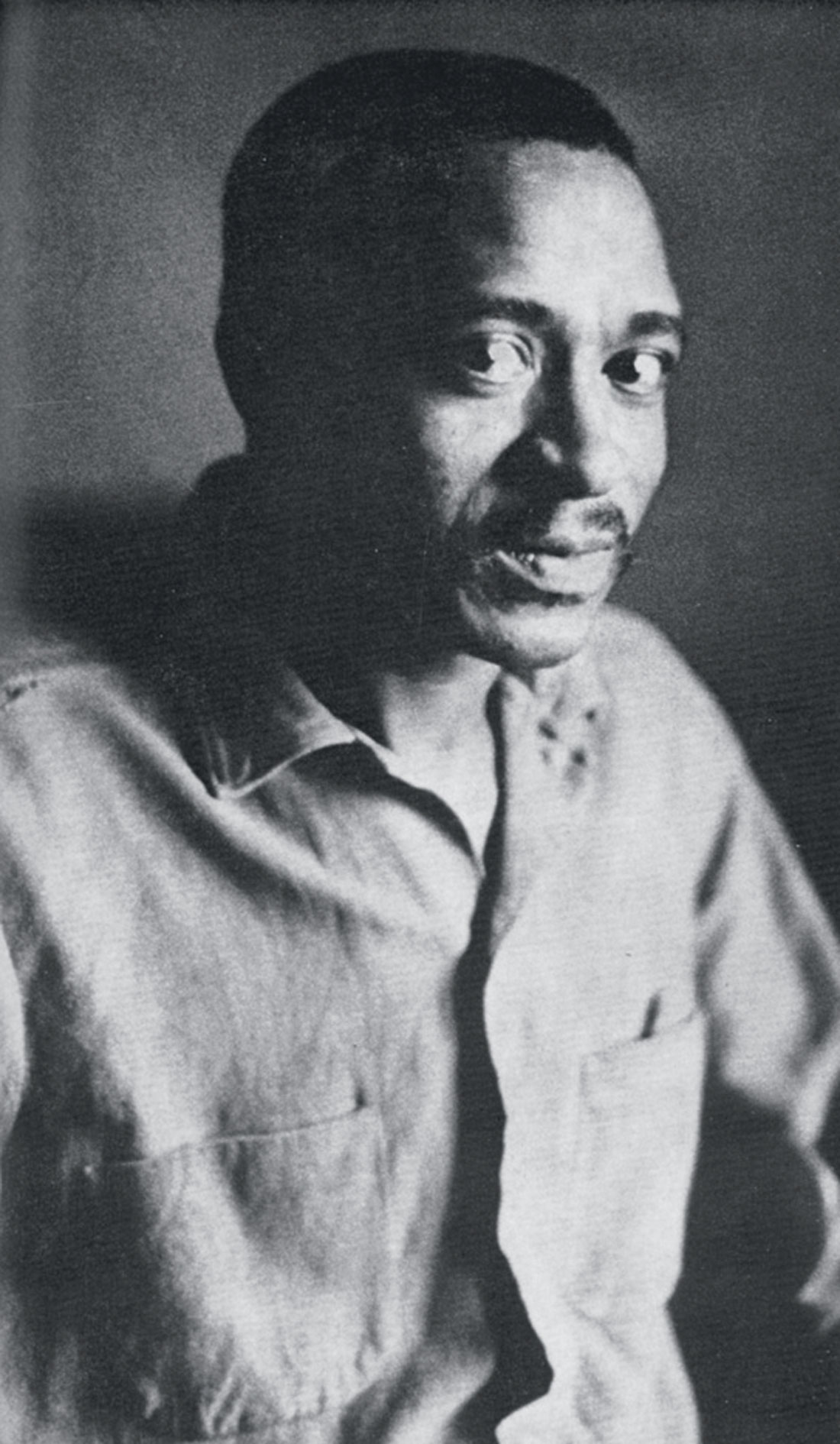

Louis Maqhubela, winner of the 1969 R200 Cambridge Shirt Award for his oil painting “Painting II”. Source: www.revisions.co.za

Louis Maqhubela, winner of the 1969 R200 Cambridge Shirt Award for his oil painting “Painting II”. Source: www.revisions.co.za

At the fifth iteration of the exhibition, in 1971, repeat judging panel member Neville Dubow noted ‘This is essentially a young artists’ show: most of them are in their thirties and a good many are very much younger. There is scarcely a figure from the commercial establishment, and no major senior generation representative.’

The 1971 exhibition was also notable for its inclusion of art that was socially and politically aware. Natal Mercury critic Barry Maritz wrote,

‘The judges, Esme Berman, Walter Battiss and Neville Dubon [sic], were obviously aiming at an exhibition of quality and balance and work that showed an awareness of the direction and problems facing a new art in South Africa.’ (Maritz 1971).

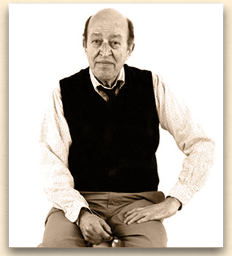

Repeat Art SA Today juror Neville Dubow. Source: www.artthrob.co.za

Repeat Art SA Today juror Neville Dubow. Source: www.artthrob.co.za

Artists such as Omar Badsha, Nils Burwitz, Norman Catherine, Malcolm Payne, Cyprian Shilakoe, Timo Smuts, Paul Stopforth and Gavin Younge submitted works with titles or imagery satirising the South African government. As Erica Clark notes, by the 1970s there was a feeling among many in the art community that an artistic response to social issues was overdue. The 1971 exhibition marked the first substantial appearance of overt socio-political protest art, according to Clark. That year’s November issue of Artlook magazine included a review of the exhibition which largely praised the artists’ work and choice of focus. Calling the show ‘a real blockbuster’, the Artlook review said,

‘here, at least, is art which communicates, and strongly, an awareness of our situation, locally, and in the world at large. Even those works which echo ideas and methods from abroad, have an energy and professionalism which place them in an international class.’ (Francois 1971)

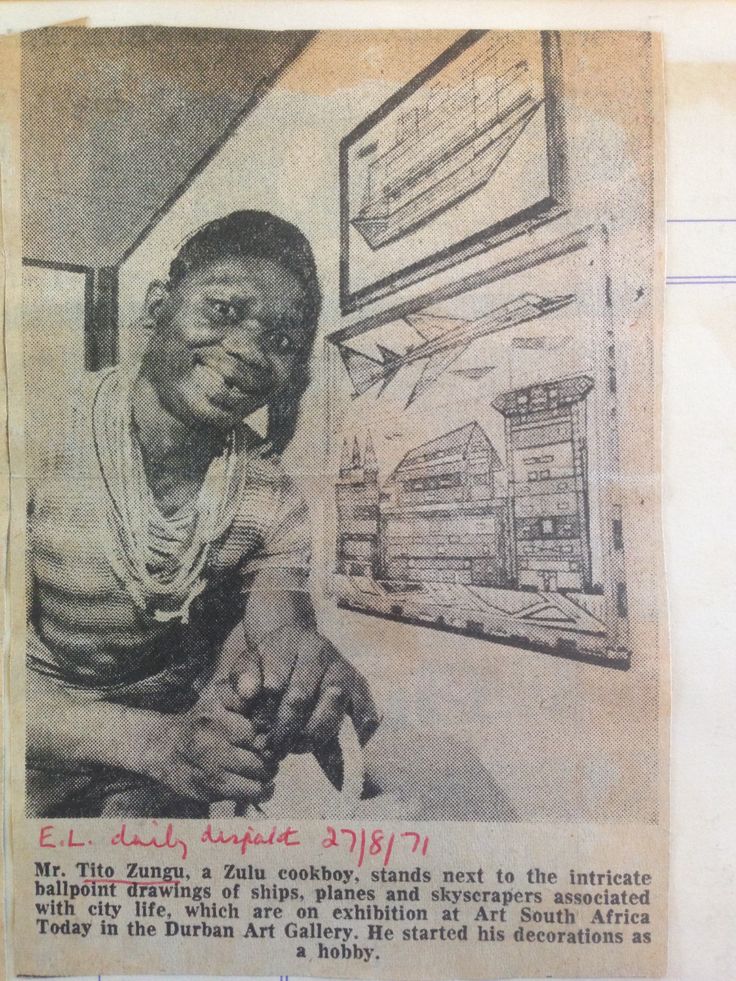

East London Daily Dispatch article on Art SA Today exhibitor Tito Zungu (National Gallery Archives). Source: s-media-cache-ak0.pinimg.com

East London Daily Dispatch article on Art SA Today exhibitor Tito Zungu (National Gallery Archives). Source: s-media-cache-ak0.pinimg.com

Considering the 1971 judges’ selection of Malcolm Payne’s professedly non-political and at least visually ambiguous ‘Swing’ as the winner of the main award, a preference for abstractions of political comment continued to dominate the art establishment. Erica Clark explains: ‘Despite being open to expressions of political protest in art, [the jurors] were perhaps more comfortable with ambiguity and allusion than with direct and unambiguous statement.’

Reviews of the 1973 Art SA Today noted contrasts to the 1971 exhibition in tone and subject matter. Revealing an assumption about artistic medium, Marilynne Holloway of the Sunday Tribune wrote that the graphic section consisted of ‘works of evocative sensitivity…. less protest art than honest emotional representation’. Marie O’Connor of the Natal Mercury contended that ‘This year has produced a less agitated cross-section of art than the previous exhibition and more generally representative of art being produced throughout the country.’ O’Connor also commented,

‘The previous Art: S.A. Today exhibition may have been more articulate and provocative than this one, but I suggest that the artists who were working along these lines have abandoned polemics as being unsuited to the visual arts, a fact which has been borne out by the return of many of these artists to a greater preoccupation with media and its presentation, plus projecting a more broadly based humanism.’ (O’Connor 1973)

Clark points out there was a prevailing view among the white art community that art and politics did not overlap: ‘it took a further ten years for overt political protest in art to reassert itself and gain recognition as a vital and necessary element in a society in crisis’. Meanwhile, many Black artists who were overtly politically engaged stopped submitting work to exhibitions seen as white. The socio-political implications of works submitted after 1971 registered similarly to many 1960s pieces in their emotional expressiveness and relative critical ambiguity.

According to the Natal Daily News, more than 17 000 people saw the 1973 showing – several thousand more than attended in 1971. ‘The Durban public seemed to accept the “way-out” art for what it was’ – despite reviewers castigating the selections made by lone juror Pauline Vogelpoel of the Tate Gallery’s Contemporary Art Society in London. Natal University fine arts professor Norman Martin noted his disappointment in the wake of 1971’s ‘“exhilaratingly high standard”’:

‘“Works which entertain the popular and sometimes rather obviously conscience-salving thing of ‘political comment’ are so transparent and lacking in sincerity that in the final analysis they are no more than mere dedicated followers of a rather doubtful fashion.”’ (Daily News Reporter 1973)

Vuminkosi Zulu, winner of an R25 Hajee Suliman Ebrahim Memorial Award at the 1973 Art SA Today exhibition. Source: www.revisions.co.za

Vuminkosi Zulu, winner of an R25 Hajee Suliman Ebrahim Memorial Award at the 1973 Art SA Today exhibition. Source: www.revisions.co.za

By 1975 the tenor of Art SA Today had evolved further from its 1971 characterization. The decision to position American art commentator Clement Greenberg as sole judge raised the profile of the event but largely disappointed audiences and critics. University of Natal fine arts department chair Raymond van Niekerk wondered whether “a bad joke has been perpetrated at the expense of South African art’. Though organising committee chairman Sylvia Kaplan waxed optimistic in the exhibition catalogue – ‘For the future it is hoped that this biennial event will continue to be adventurous in spirit and exhibit art of quality which communicates freely’ – this was the last of the Art SA Today showings. Criticizing Greenberg’s choices, Barry Martiz told the Natal Daily News, ‘“I think he’s done a lot of harm because people won’t understand his reasoning. The rest of the country will simply write off Art South Africa Today.”’ Yet, even in the responses of art writers noting their dissatisfaction with Greenberg’s involvement, some noted ‘the implicit acceptance of revolutionary aesthetic criteria’. Durban artist and lecturer Andrew Verster: ‘“You get the feeling that all the works (and some of them are dreadful) were chosen to put across a point of view”’.

Clement Greenberg, sole juror of the 1975 Art SA Today exhibition. Source: www.sharecom.ca

Clement Greenberg, sole juror of the 1975 Art SA Today exhibition. Source: www.sharecom.ca

Despite the generally disappointing denouement, Art SA Today left a legacy of innovative thinking and inclusivity. Analysis of the exhibitions disproves assumptions that South African political art developed post-1976, even within the confines of the institutionalized art establishment. Criticisms of the showings’ most politically charged inclusions worried about gimmickry and unaesthetic technique, but the sense that the artworks conveyed sincerity and substance generally prevailed.