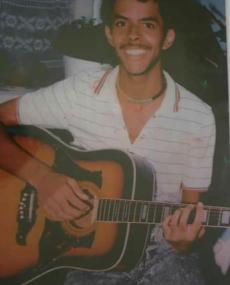

Robbie Waterwitch, a member of MK, was a lover of music and playing the guitar. Image source

Robert ‘Robbie’ Anthony Basil Waterwitch was born on 15 July 1969 and grew up in Athlone, a suburb of Cape Town located on the Cape Flats. Remembered as a sensitive and quiet, yet passionate, young man who had a love for music, especially jazz, and a gifted guitar player, Waterwitch’s political awakening came in high school. A student at St. Columba’s High School in Athlone, and a devout Catholic himself, Waterwitch experienced resistance from the Roman Catholic church leaders at the school when, together with some of his peers, he tried to establish a Student Representatives Council (SRC). Waterwitch’s endeavours in establishing a SRC - although opposed - were ultimately successful, and for it he is described as a pioneer by his uncle, Basil Snyers. After his schooling at St. Columba’s, Waterwitch pursued a Bachelor of Arts degree at the University of the Western Cape (UWC), where he also became a leader among the United Democratic Front (UDF) Youth of Belgravia.

Remembered for his religious commitment and his commitment to the liberation struggle, Waterwitch was inspired by the Sandinista revolution in Nicaragua. From the Nicaraguan revolution, Waterwitch came to a better understanding of national liberation and learnt about Catholic liberation theology, and thereby found a means to reconcile his religious duty with his duty towards the liberation struggle in South Africa. A friend, Robbie van Niekerk, wrote this of Waterwitch: “I am now not surprised that Robbie was so attached to the Sandinista Revolution in Nicaragua - it represented I think a key to his own deeply held belief that religious commitment was completely compatible with the struggle to create a better society.”[1]

A member of uMkhonto weSizwe’s (MK)Ashley Kriel Detachment, the period of Waterwitch’s induction into MK is not exactly known. At the Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC) of South Africa human rights violations hearing, Snyers, appearing on behalf of the family, explained that they were not aware that he was a member of MK. In a mini-documentary on his political life and death, his mother, Hettie Waterwitch, stated that she assumed that he was affiliated with the African National Congress (ANC) by virtue of the colours (green, black and yellow) of his beaded necklace.

Waterwitch’s death on 23 July 1989 presently remains a contentious matter. On the particular Sunday evening, Waterwitch and fellow MK operative Coline Williams set out to plant a bomb at Athlone Magistrate’s Court. Their mission was part of a broader anti-election bombing campaign which sought to target various election sites across the Cape Peninsula in an attempt to disrupt the Tricameral Parliament elections. Bombs were detonated at Somerset West Magistrate’s Court and Mitchell’s Plain police station. A bomb blast planned for Bellville Magistrate’s Court was prevented when security forces intervened. The bomb planned for Athlone Magistrate’s Court, however, did detonate. In fact, Snyers and Williams’ sister, Selina Begg, née Williams, recall hearing the explosion. However, the mission was unsuccessful as Waterwitch’s and Williams’ disfigured corpses were found behind the public toilets opposite the police station and court, having apparently been killed by the premature detonation of the bomb.

Although the TRC could not definitively determine the truth surrounding the deaths of Waterwitch and Williams, the commission could establish that the Ashley Kriel Detachment was infiltrated by Military Intelligence. Aristedes Spannelis of the Directorate of Covert Collections (DCC) corroborated that he was the handler of a double agent, Shane Oliver, inside the detachment. Having access to the weaponry, the TRC determined that it could be possible that through Oliver, the bombs could indeed have been rigged, resulting in the premature detonation of the explosives and deaths of Waterwitch and Williams. Furthermore, the Commission also determined that Geoffrey Brown, a close friend of Waterwitch, had been an informant for the National Intelligence Service (NIS). Although the entire truth about the deaths of Waterwitch and Williams could not be determined, what is certain is that Waterwitch and Williams’ mission was compromised from the onset.

Another version of the cause of their deaths, however, implicates the apartheid state security agents. According to this version, Waterwitch and Williams were apprehended, blown up with explosives and positioned behind the public toilets. This was a common tool of subversion implemented by state security agents to not only portray the idea of incompetence among liberation fighters and undermine the liberation struggle, but also to lower the morale of activists.

A joint funeral was held for Waterwitch and Williams at St. Mark’s Catholic Church in Bonteheuwel. The funeral, attended by approximately 5,000 people, was politically charged. The coffins were draped with the colours of the ANC and attendees flew flags of the ANC and some wore political organisation’s t-shirts, such as the UDF. At the time, political statements were banned at funerals. The police monitored the funeral closely, carrying with them tear gas canisters and automatic guns. The funeral, however, was disrupted with violence when police fired teargas and attacked the attendees upon their arrival back to the church from the gravesite.

In 2005, the City of Cape Town erected a memorial opposite the Athlone Magistrate’s court in honour of Waterwitch and Williams. The memorial depicts a cautious Waterwitch and Williams walking side by side as though frozen in time proceeding along to fulfill their mission. The memorial was, however, stolen in March 2008, and thereafter re-erected.

[1]R. van Niekerk, ‘Memories of Robbie Waterwitch and a South African Sunshine,’ Oxford, 17 July 2009.