Zuleikha Mayat was born in 1926 in Potchefstroom, Transvaal (now North West Province). Her father, Mohamed Bismilla, was a prominent business person who first came to South Africa from India at the age of five with his stepmother. Her mother, Amina, was also from India. Growing up, Mayat and her siblings’ lives revolved around their parent’s shop, which was very popular within the community. Later, Mayat would attribute her caring nature to her father, who generously never turned away a customer even if they were short of cash.

Mayat completed her primary level education at the local Potchefstroom Indian Government School but could not progress as there was no school available in the area that could accommodate her due to the segregationist apartheid laws (the only available school was for White learners). Her brothers encouraged her to obtain her matric via correspondence, which she did, passing with an exemption from the Joint Matriculation Board in 1945. Unable to study medicine like her brother Nasim, Mayat was forced to abandon her dream of becoming a doctor but completed short courses in journalism instead.

Nasim went to study medicine at the University of the Witwatersrand Medical School in Johannesburg, Transvaal (now Gauteng) and would bring his friends and fellow students home during the holidays. One of these friends was Mohamed Mayat, whom Mayat married in 1947. They moved to Durban, Natal (now KwaZulu-Natal), shortly afterwards and lived with Mohamed’s parents. This family unit would eventually be broken, however, by the Group Areas Act of the 1960s. The couple bought a home in Clare Estate, Durban, where they became neighbours of celebrated photographer, Ranjith Kally.

It was in Durban that Mayat would make her mark in various fields of activism. Both she and her husband were progressive, open-minded people and got involved in various political and social activities. She began writing in the women’s column – Fahmida’s World – of the weekly Gujarati/English newspaper, Indian Views, which Moosa Meer, father of Professor Fatima Meer, was the editor.

In 1954, Mayat became a founding member of the Women’s Cultural Group (WCG), a forward-thinking women’s organisation that sought to bring about social change. The women met up regularly to discuss ways to empower women. This was a remarkable development in a society that was still very conservative when it came to involving women in the public sphere.

Although the majority of members were Muslim women, membership was open to women across all religious, racial, and class boundaries. Consequently, the group soon became multicultural, comprising of women from all walks of life – Black, White, Christian, Hindu, Jewish, and so on (however, in more recent years, it is only comprised of Muslim women).

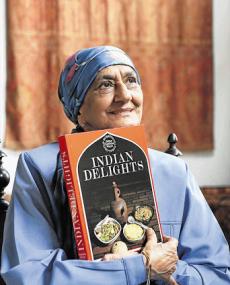

Mayat, who started writing at the age of fourteen, authored a small cookbook as a way for the WCG to raise funds. That cookbook was the iconic, Indian Delights, first published in 1961. This was not an easy feat, however, as the women struggled to raise funds for the first edition. When they approached a publisher by the name of Mr Ramsamy, he agreed that they could pay him over six months but the book was so well- received – flying off the bookshelves – that they managed to settle their debt in three months.

Since its first edition, the book has enjoyed sales in South Africa as well as internationally. Having sold more than 500 000 copies, it remains one of the best-selling books of any genre in South Africa.

In addition to the first edition, a subsequent fourteen editions have been published. The group uses funds generated from book sales for a range of charitable causes. These include providing bursaries to disadvantaged tertiary students from all races and religions annually (the WCG was the first non-profit organisation to issue interest-free loans to students at tertiary institutions), running soup kitchens for the poor, providing sandwiches to school children every week, providing blankets for the poor during winter seasons, hosting educational lectures and cultural events like poetry recitals, as well as developing programmes that upgrade the skills (like sewing programmes) of disadvantaged women in particular. Their bursary programme has played an instrumental role in helping countless students complete their education in a country where access to quality education can be challenging for many.

Mayat has authored several other books, including Quranic Lights (1966-2012), Nanima’s Chest (1981), A Treasure Trove of Memories (1996), her semi-autobiography, History of Muslims of Gujarat (2008), and the historical fiction, The Odyssey of Crossing Oceans (2021). She has also written Urdu poetry under the pen name, Fehmida. While Indian Delights is undoubtedly her most defining work, Mayat prefers to be acknowledged for her other books which share her worldwide travels and religion.

Although WCG did not involve itself in politics during its early years, Mayat did in her personal capacity. She worked with the Black Sash and along with her husband, often interacted with and housed anti-apartheid activists who were on the run from the authorities.

The couple was very close friends with Prince Mangosuthu Buthelezi and his now late wife, Irene (who on many occasions stayed over at their home), as well as with Ismail Meer and his wife Fatima. When the Meers were under security police surveillance and needed safe houses for apartheid activists, the Mayats offered their home and as a result, Nelson Mandela took shelter in their home a couple of times. Mahomed Mayat would pick him up and drop him off in the morning at a nearby garage. Thus, they attracted the attention of the authorities who ransacked their house a few times. On one occasion, their home was raided in the wee hours when Moosa 'Mosie' Moolla escaped from prison in 1963. Fortunately, they were the only ones at home.

Due to apartheid, her husband could not specialise and so they decided to move to London, England, for a year, leaving their three young children with her sisters-in-law. While her husband specialised in obstetrics and gynaecology, Mayat completed courses in journalism and Islamic Studies at the University of London.

Another result of apartheid was that both Mayat and her husband were denied the right to own passports but were begrudgingly allowed to leave the country to attend medical conferences. The couple frequently took advantage of this and travelled widely, visiting countries like Russia and Japan. Their travels culminated in a book titled, Journeys of Binte Batuti (2015).

In 1968, Mohamed teamed up with two other doctors (Dr Motala and Dr Khan) to open the Shifa Hospital in Durban, which provided quality medical services to Blacks. The hospital employed professionals of all races and paid them equally. During its early days, Mayat supervised the food, laundry, and other housekeeping.

In March 1979, Mayat, along with her husband, niece, and sister, Bibi, were involved in a car accident when a drunk driver drove into them. Mayat and her niece survived, but her husband and sister did not. When the ambulance drove her husband (who was dying from loss of blood) to the nearest hospital, he was denied treatment because of his race as it was a Whites-only hospital. The hospital staff directed them to a hospital reserved for Black people but because it was much farther away, he did not survive the journey.

The tragic loss of her husband and sister did not deter her from continuing with her public and community work. If anything, this event seemed to spur her on even more as she plunged herself deeper into her work and extended her activities. As such, Mayat has been involved with countless organisations like the then-Natal Indian Blind and Deaf Society, the orphanage Darul Yatama Wal Masakeen, and the Institute of Race Relations (IRR) over the years.

During the University of Durban-Westville (UDW – now known as the University of KwaZulu-Natal - UKZN) student boycott, Mayat and Fatima Meer were on the parents’ committee. Together with Betty Shabazz (Malcolm X’s wife), who visited the Mayat’s home, they took food to the detained students.

The death of her husband further brought her into contact with Ahmed Kathrada, who was at that time serving his prison sentence on Robben Island. Upon hearing the news of the passing of his friend, Kathrada penned a letter of condolence to Mayat’s brother, Abdul Haq, a former flat-mate of Kathrada. Mayat’s brother lived in Canada so her mother asked her to respond, thus sparking the beginning of a decade long correspondence between Mayat and Kathrada, during which seventy-five letters were exchanged between the two.

The letters, which focused on culture, politics, as well as religion, were published as a book in 2009 called Dear Ahmedbhai, Dear Zuleikhabehn: The letters of Zuleikha Mayat and Ahmed Kathrada 1979-1989. This book has enjoyed international recognition and highlighted some of the effects and injustices of apartheid from a day-to-day perspective.

The advent of democracy and old age has not made Mayat slow down. She continues to fight for social justice and the rights of the disadvantaged. For example, she has been actively involved in Palestinian protests with people like Ela Gandhi, granddaughter of Mahatma Gandhi, and Paddy Kearney (now late) and continues to be a central figure within the WCG.

In 2012, Mayat was awarded an Honorary Doctorate in Sociology by UKZN. She was also honoured in 2019 with a Lifetime Achievement Award during a function hosted by the Iqraa Trust in celebration of her life’s work – just one of the numerous accolades she has received from organisations over the years.

As an award-winning author, a social activist, and a founding member of WCG who has earned respect in both her country of birth and internationally, Mayat has played an essential role in creating public awareness about various social issues from education and culture to religion. She has spearheaded many projects aimed at offering a helping hand to the disadvantaged, uplifting those who needed it and empowering women in a society in which they are often subjected to multiple forms of oppression because of their race, gender, and class.