Nelson Rolihlahla Mandela

Childhood in the Eastern Cape

Mandela in Umtata, in his first suit, presented to him by the Paramount Chief of the abaThembu, Jongintaba Dalindyebo. © Mayibuye Centre.

Nelson Rolihlahla Mandela was the son of Nonqaphi Nosekeni and Henry Mgadla Mandela, a chief and chief councillor to the paramount chief of the Thembu and a member of the Madiba clan. Mandela’s original name was Rolihlahla, which literally means ‘pulling the branch of a tree’, or colloquially, ‘troublemaker’. He was given the name, ‘Nelson’, by his White missionary school teacher at the age of seven. He has also been known as Dalibunga, his circumcision name, as well as Madiba, his clan name. His father, Mgadla, was one of the grandsons of Ngubengcuka, a king of the abaThembu and leader of the Madiba clan.

Mgadla Mandela, in line with the traditional leadership structures, was chief of the Mvezo district. Mgadla was a traditionalist and Nonqaphi was his third wife. He was involved in a minor dispute with the local White magistrate regarding cattle and refused a summons to appear before the magistrate as he did not believe that the matter fell under the colonial government's purview. As a result, he was charged with insubordination and the colonial authorities stripped him of his chieftainship, land and cattle on the 1 October 1926 without any consultation with the Paramount Chief, Sampu Jongilizwe. The Mandela family was thus forced to move to Qunu, a little village in the Eastern Cape. Mgadla Mandela was known to be a close confident and senior councillor to his cousin, King (Paramount Chief) Jongintaba Dalindyebo whom Mgadla recommended for the position in 1928.. Another factor in Jongintaba's election was the fact that the chosen heir, Sabata Dalindyebo, was too young to rule as Paramount Chief. In 1930 when his father died, Mandela was placed under the care of Jongintaba. The adoption into the royal abaThembu family meant that Mandela moved from Qunu to ‘the Great Place’ at Mqhekezweni.

Education

In 1934, at 16 years old, Mandela went to initiation school to undergo ulwaluko, a traditional ceremony that whereby young boys transition into manhood (For more information on this ceremony, click here). In the same year, Mandela enrolled at Clarkebury, a school run by C.C Harris. It was here that Mandela was first introduced to a western style of education. At the age of 19, Mandela was enrolled at Healdtown, the Wesleyan College of Fort Beaufort, which was a Mission School of the Methodist Church. Healdtown was the largest school for Africans with more than a thousand students. The school curriculum focused on British history but his history teacher, Weaver Newana, added his own oral history about the wars between the British and amaXhosa. Mandela’s nephew, Justice Dalindyebo, four years his senior, was already enrolled at the school. . Mandela was the first member of his family to attend high school and he developed a love for boxing and long-distance running. He also developed a great interest in African culture (under the influence of his teacher, Mr Newana). He matriculated at Healdtown Methodist Boarding School in 1938 and as such, formed part of a very small number of black pupils who had attained a high school education in South Africa.

The patronage of Mandela’s relative, Paramount Chief Dalindyebo, resulted in Mandela joining the Regent’s son, Justice, at the University of Fort Hare, near Alice in the Eastern Cape, the only university for Blacks (African, Coloured and Indian) in South Africa at the time. At Fort Hare, Mandela befriended African, Indian and Coloured students, many of whom went on to play leading roles in the South African liberation struggle and in the anti-colonial struggle in some African countries. One of Mandela’s fellow students was Oliver Tambo. They would later become partners in their law firm, close comrades and lifelong friends. Another notable friend Mandela made at Fort Hare was Kaizer Daliwonga Matanzima, a man who would become a political opponent. By law and custom, Matanzima was also Mandela’s nephew as they came from the same royal family. Mandela did not complete his degree at Fort Hare. He was involved in a dispute related to elections of the Student Representative Council (SRC) in 1940. Mandela refused to take his seat on the council as the majority of the students had not voted in the election. This was due to a boycott of the elections over university food and desire among the students to give more power to the SRC. After he rejected the university’s ultimatum to take his elected seat or face expulsion, the university gave him until the end of the student holidays to think the matter through, but he felt there were principles at stake that could not be compromised. He informed his guardian that he would not be returning to Fort Hare.

The move to Johannesburg

The Regent had also made arrangements for his son Justice and Mandela to marry two young women chosen by the Regent. Both young men decided to defy the Regent, stole two of his cattle and used them to raise funds to secretly leave for Johannesburg. Once there, Justice took a job as a clerk with Crown Mines which had been arranged for him by his father some months earlier. Justice then approached a headman, or induna, who was employed at the mine to give Mandela a job as a mine policeman. An induna typically acted as a second in command to a chief. In the apartheid era, this had evolved into something new. The induna would act with the chief’s authority at the mine compounds, ensuring that the rule of law was maintained among the men when they were away from home. Within days of arriving, both Justice and Mandela were dismissed when the induna learnt they had defied Dalindyebo and had left Mqhekezweni. Mandela found temporary lodging in Alexandra townships and communicated to the Regent his regret about defying and disrespecting him. Mandela convinced Chief Dalindyebo that he wanted to further his study in Johannesburg and received the Regent’s consent to remain in Johannesburg as well as financial support.

A few months into his stay in Johannesburg, Mandela was introduced to a young estate agent named Walter Sisulu, who immediately took him under his wing. Sisulu had joined the African National Congress (ANC) in 1940 and would prove to have a great influence over Mandela as a lifelong friend, political mentor and closest political confident. Mandela moved in with Sisulu and his mother in their home in Orlando, Soweto. Furthermore, Sisulu found Mandela a White firm of attorneys who were prepared to give him a job and register him as an articled clerk, an exceedingly rare offer in segregated South Africa. While working at the firm, Mandela enrolled for a BA degree in law at the University of Witwatersrand (Wits) after completing his BA from Fort Hare University via correspondence. At Wits, he befriended fellow students I.C. Meer, J.N.Singh, Joe Slovo and Ruth First, all of whom were members of the Communist Party of South Africa (CPSA) [later renamed as the South African Communist Party (SACP)]. Mandela became very close to I.C. Meer and J.N. Singh, both of whom played leading roles under the leadership of Dr. Yusuf Dadoo in making the Transvaal and Natal Indian Congresses become mass-based and militant organisations. Both Meer and Singh would serve prison terms during the 1946 Indian Passive Resistance campaign.

Political beginnings

In 1944, Mandela joined the African National Congress (ANC) and soon became part of a group of young intellectuals that included Walter Sisulu, Oliver Tambo, Anton Lembede, and Ashley Mda. The group articulated its dissatisfaction with the way the ANC was being run, critiqued its policy of appeasement, and became the driving force in the formation of the ANC Youth League (ANCYL) in April of the same year. Influenced by the Natal and Transvaal Indian Congresses’ Passive Resistance campaign of 1946 and the 1946 Mineworkers Strike, the ANC Youth League, led by Mandela, Sisulu and Oliver Tambo, began drafting what came to be known as the Programme of Action for the ANC. This called for the ANC to become a more militant organisation, and would only be adopted by the ANCYL’s parent organisation in 1949. One can view the tangential influence of Mandela’s friendship with I.C Meer and J.N Singh here, as they were involved in the Indian Passive Resistance Campaign which proved so influential in guiding the ANC’s future resistance movements.

Nelson Mandela and Evelyn Mase at Walter Sisulu's wedding in 1944. Photograph: Eli Weinberg.

On 15 July 1944, Mandela married Evelyn Mase, a nurse at Johannesburg General Hospital and Walter Sisulu's cousin. The newlyweds moved to live with Evelyn's married sister in Orlando and became neighbours with Es'kia Mphalele, a teacher and later a noted scholar, journalist, writer and activist. In 1945, Evelyn Mandela gave birth to the couple's first child, a boy named Madiba Thembekile (Thembi for short). They were able to get a council house in Orlando, which had three rooms but neither electricity nor an inside toilet. Mandela's younger sister, Nomabandla (Leaby), came to live with them and enrolled at Orlando High School. Evelyn was the breadwinner in the family while Mandela studied law at Wits where he devoted much of his time to politics. Evelyn was described by Nomabandla as not wanting to hear a thing about politics, yet she was very supportive of her politically minded husband. However, Mandela’s busy political and academic life meant that the burden of care-giving and homemaking also fell to Evelyn, in addition to her role as breadwinner. In 1946, Mandela and Evelyn had their second child, a daughter named Makaziwe. Makaziwe would tragically pass away at 9 months old.

In 1948, the National Party (NP) narrowly won a Whites-only national election on the platform of a new policy of total racial segregation called apartheid (which translates from Afrikaans as ‘apartness’). By this stage, Mandela was National Secretary of the ANCYL. Mandela, Sisulu and Tambo began lobbying the ANC to embark on militant mass action against a plethora of new segregationist laws that the Nationalist Party were drawing up to give effect to the new policy apartheid. The lobbying paid off as at the ANC’s annual conference in December 1949, the Youth League’s Programme of Action was adopted by the parent organization. From an organisation which believed it could, through persuasion, wring concessions from the White government, the ANC now became a militant liberation movement. The Programme of Action called on the ANC to embark on mass action, involving civil disobedience, strikes, boycotts and other forms of non-violent resistance. Furthering the ideological influence of the ANCYL on the ANC as a whole, Walter Sisulu was elected as Secretary General at the conference.

From its inception the ANCYL was heavily influenced by the strident African nationalism espoused by its inaugural President, Anton Lembede. His biography on this site states that "[h]e is best remembered for his passionate and eloquent articulation of an African-centred philosophy of nationalism that he called "Africanism". A call to arms for Africans to wage an aggressive campaign against white domination, Africanism asserted that in order to advance the freedom struggle, Africans first had to turn inward. They had to shed their feelings of inferiority and redefine their self-image, rely on their own resources, and unite and mobilize as a national group around their own leaders. Though African nationalism remains to this day a vibrant strand of African political thought in South Africa, Lembede stands out as the first to have constructed a philosophy of African nationalism. Mandela was a strong advocate of the Lembede line that the ANC should stand on its own and not enter into alliances with the Indian Congress, the Communist Party or the Non-European Unity Movement (NEUM). Indeed, the Youth League’s policy of going it alone brought it into tension with the older generation ANC and led to the League opposing some of the most important campaigns of the 1940s, including the Mine Workers Strike, the Indian Passive Resistance Campaign and the cooperation pact signed between the ANC President Dr Xuma and the South African Indian Congress (the ‘Doctor’s Pact’).

Political campaigns

Mandela burns his passbook in an act of Defiance against apartheid pass laws. Photograph: Eli Weinberg, UWC Robben Island Mayibuye Archives.

In 1950, when the CPSA, the Transvaal and Natal Indian Congresses, and the newly elected ANC President-General Dr James Sebe Moroka jointly endorsed the Defend Free Speech Convention, Mandela, along with the rest of the ANCYL leadership, was strident in his criticism. The Youth League believed that the endorsement by Dr Moroka undermined the ANC’s Programme of Action. Notwithstanding his Africanist political stance, Mandela did not allow the issue to influence his personal relationships with Indian, White and African communist leaders. A pivotal moment in the struggle against apartheid came in May, 1950. At the Convention, the represented parties called for a national strike to protest the proposed banning of the Communist Party. Once again, the ANCYL opposed the organisation of this strike. Elinor Sisulu writes, in her book ‘Walter and Albertina Sisulu: In Our Lifetime’ that “[t]he Youth Leaguers opposed the strike because the ANC had not initiated the campaign. They saw the decision to hold a May Day strike as further evidence that the communists and the Indian Congress wanted to undermine the Programme of Action and steal the thunder of the ANC.” However, the 'May Day' (1 May) strike was immensely successful and the government responded with unrestrained brutality. Furthermore, the Unlawful Organisations Bill, which was the legislation behind the banning of the SACP, was broad enough that any dissident party wanting social or political change could be labelled communist and banned. An emergency meeting was called, with Dr Moroka presiding, consisting of the ANC Youth League, South African Indian Congress (SAIC), Communist Party, the African People’s Organisation (APO), and the Transvaal Council of Non-European Trade Unions.

A change in Mandela’s ideological stance is indicated by the fact that when Dr Yusuf Dadoo called for a united front against the apartheid government, Mandela agreed. Elinor Sisulu writes that Mandela recalled, “It was at that meeting that Oliver [Tambo] uttered prophetic words: ‘Today it is our Communist Party, tomorrow it will be our trade unions, our Indian Congress, …. our African National Congress.’” Confronted by opposition from the ANC’s Africanist wing, Mandela stuck by this new position and together with Tambo and Communist Party general secretary Moses Kotane, they joined their friend Walter Sisulu in forging what came to be known as the Congress Alliance. In 1952, the Congress Alliance embarked on the first of its national campaigns against a select number of Apartheid government’s laws. The campaigns were modelled on the earlier passive resistance campaigns of the 1940s.The main Congress Alliance campaign was named the Defiance Campaign, which continued for two years. While the campaign did not succeed in changing any laws, it transformed the ANC into a mass-based and militant organization and the largest of the liberation movements, growing from 7000 to over 100 000 by the time the campaign ended in 1954.

Nelson Mandela pictured in 1952 at the offices of his legal partnership with Oliver Tambo. Photographer: Jürgen Schadeberg.

During the Defiance Campaign, Mandela emerged as one of the most influential leaders of the liberation struggle, alongside Walter Sisulu and Chief Albert Luthuli. Before the Defiance Campaign began, Mandela was serving as the President of the ANC Youth League. He was then made the public spokesperson and leader of the campaign itself, having been appointed National 'Volunteer-in-chief'. Together with Maulvi Cachalia of the Transvaal Indian Congress (TIC), Mandela travelled around South Africa enlisting volunteers to defy apartheid laws. Subsequently, both were charged with recruiting and training ‘congress volunteers’. As a result of his abilities as a mass leader, Mandela was elected the ANC Transvaal President as well as Deputy National President in 1952.

The campaign officially began on 26 June 1952 when 51 volunteers led by President of the Transvaal Indian Congress Nana Sita and Patrick Duncan entered the Boksburg Native Location in defiance of the law that required non-Africans to have permits to enter an African location. In the course of the campaign thousands of volunteers served harsh prison terms, but Mandela was instructed not to break the law or court arrest to ensure that the campaign would not be rendered leaderless should all the leaders be imprisoned at the same time. He was nevertheless arrested on several occasions during the course of the campaign and released after short stints in jail.

At the height of the Defiance Campaign, the ANC recognised the likelihood that the organisation would be banned as the Communist Party had been three years earlier. Asked by the ANC executive to devise a contingency plan for such an eventuality, Mandela drew up what became known as the 'M Plan', which provided for the creation of street-based cell structures. This structure would provide more security and secrecy for the organisation in the event of the banning. This meant that the ANC was moving away from public events such as rallies and speeches towards more ‘underground’ activities.

During the same period, Mandela become increasingly uneasy with the policy of non-violent resistance, but was held back by the ANC leadership’s strong advocacy of non-violence. This is evidenced by the following quote from an interview with Richard Stengel from the 1990s:

The Chief [Albert Luthuli] was a passionate disciple of Mahatma Gandhi and he believed in non-violence as a Christian and as a principle. Many of us did not because when you regard it as a principle you mean throughout, whatever the position is, you’ll stick to non-violence. We took up the attitude that we would stick to non-violence only insofar as the conditions permitted that. Our approach was to empower the organization to be effective in its leadership. And if the adoption of non-violence gave it that effectiveness, that efficiency, we would pursue non-violence. But if the condition shows that non-violence was not effective, we would use other means.

In December 1952, Tambo joined Mandela as a partner in his legal practice - the first African-run legal partnership in the country. During the next two years Mandela and Tambo worked together in their legal practice defending hundreds of people affected by apartheid laws. Their practice became very successful. During the same month Mandela and 19 other leading Congress Alliance activists were arrested and charged under the Suppression of Communism Act. Mandela, like all the others, was sentenced to nine months imprisonment with hard labour, suspended for three years. He was also served with a banning order that prohibited him from attending gatherings for six months and from leaving the Johannesburg magisterial district. For the following nine years, his banning orders were repeatedly renewed which served the purpose of limiting Mandela’s sphere of influence to Johannesburg.

Mandela with Moses Kotane outside the Old Synagogue, Pretoria, on the day when the last of the accused were finally acquitted. Photograph: Jürgen Schadeberg

Although Mandela was officially the deputy national president of the ANC, he was not legally allowed to play any role in ANC activities because of his banning order. However, he continued to meet clandestinely with the ANC and Congress Alliance leadership. In this way, he was able to play a key role in the planning of all the major campaigns after 1952. The ANC-led Alliance called off the Defiance Campaign at the end of 1953 after the government passed new legislation proposing very harsh sentences for people breaking apartheid laws.

One of the most important Congress Alliance campaigns was the Freedom Charter campaign. Mandela along with his banned colleagues Dr. Yusuf Dadoo, Moses Kotane and Joe Slovo played a leading role. The campaign culminated in the convening of the historic Congress of the People on 25-26th June 1955 in Kliptown near Soweto. However Mandela, Sisulu and Ahmed Kathrada could not attend the conference because their banning orders prohibited their participation. They viewed the proceedings of the Kliptown conference from the rooftop of a nearby Indian-owned shop. At the end of 1955, while Mandela was imprisoned for two weeks, Evelyn Mase, his wife, moved out of their home. Their marriage had become strained due to Mandela’s increasing devotion of time to politics. Evelyn was a member of the Jehovah’s Witness Christian following and did not have any interest in politics. This tension between the two was further exacerbated by the tragic death of their second child, Makaziwe, of meningitis at 9 months, in 1947. They were subsequently divorced in 1957.

Mandela was one of 156 African, Indian, Coloured and White men and women leaders in the Congress Alliance who were arrested and charged with treason, following a police raid in December 1956. For four-and-a-half years the Treason Trial dragged on with charges being periodically withdrawn against some of the accused.

In 1958, half way through the trial, Mandela married Nomzamo Winifred Madikizela, a social worker 16 years younger than him, from Bizana in the Transkei, Eastern Cape.

In March 1961, Justice Rumpff found Mandela and the remaining 36 accused not guilty of treason and discharged them.

Turn to the Armed Struggle

In 1959, with the Treason Trial still in progress, the ANC planned an anti-pass law campaign to begin on 31 March 1960. However, the campaign was pre-empted by the newly formed Pan Africanist Congress (PAC). The PAC was formed because of an ideological split within the ANC. Specifically, the split revolved around the ANC’s move away from an Africanist position, evidenced by the adoption of the Freedom Charter. As such, those who advocated an Africanist stance, split from the ANC in 1959, with Robert Mangaliso Sobukwe elected as its first president. The PAC called for mass peaceful anti-pass protests on 21 March 1960. Heavily armed police outside a police station in the small southern Transvaal (now Gauteng) township of Sharpeville opened fire on a peaceful gathering of protesters, killing 69 people and wounding more than 200 others, many of whom were shot in the back as they fled. The Sharpeville Massacre changed the face of South African politics as on 30 March 1960, the government declared a state of emergency. Mandela and 2000 other political activists across all liberation movements were detained as a result of this.

Furthermore, on 8 April 1960, the government banned the ANC and PAC. The banning of political organisations and the shutting down of space for political protest prompted Mandela to begin seriously thinking about the armed struggle. The discussion to take up arms against the apartheid regime was also being discussed independently by activists detained under the emergency regulations as well as some leaders who had gone underground across all the remaining anti-apartheid groupings. The underground Communist Party had already smuggled a small group of people out of the country to receive military training in China.

Mandela addressing the All in African Conference at Plessislaer Hall in Pietermaritzburg in 1961. Source: Baileys African History Archive (BAHA)

Mandela and Tambo’s law firm had virtually collapsed by this time, and Mandela rarely saw his family because of his semi-clandestine life. In August, when the state of emergency was lifted, Tambo was smuggled out of South Africa to establish an ANC office abroad. With the release of political detainees, Mandela immediately became involved in discussions about convening a national convention. He was made secretary of the organising committee of the All-In Africa Conference and secretly travelled around the country preparing for the meeting. The All-In Africa Conference was held in Pietermaritzburg, Natal (now KwaZulu-Natal –KZN0 on 22 March 1961 and was attended by 1400 representatives from 145 political, cultural, sports and religious organisations. This conference was called in response to the calling of the state of the emergency. It called for countrywide demonstrations as well as the joining of all anti-apartheid forces, regardless of racial identity of the organisations involved. A full list of the resolutions can be found here. Mandela's banning order expired on the eve of the conference. Anticipating that his ban would be renewed, he went into hiding and made a dramatic appearance at the conference, where he made his first public speech since his first banning in 1952.

The conference appointed him honorary secretary of the All-In African National Action Council, whose task was to organise a three day stay-at-home on 29, 30 and 31 May 1961 to coincide with the proclamation of South Africa as a Republic on 31 May. This was the last public meeting he addressed for the next 29 years. On 3 April 1961 Mandela issued a statement on behalf of the All-in African National Action Council calling on students and scholars to support the stay-at-home campaign.

Immediately after being acquitted in the Treason Trial, which had begun in 1956, Mandela went underground. He and Sisulu secretly travelled around the country organising the strike, and Mandela (nicknamed the Black Pimpernel at the time) remained a fugitive for the next 17 months. Mandela called off the stay-at-home protest on its second day after massive police repression of strikers. The failure of this action was important in changing his political thinking and he became more committed to the formation of Umkhonto we Sizwe (the Spear of the Nation, also known as MK) as the military wing of the ANC.

Nelson Mandela, second from left, and Robert Resha, fourth from the left, with members of the National Liberation Front in Algeria, 1962. Source: Pretoria News Library

Mandela and some of his colleagues concluded that violent resistance in South Africa was inevitable and that it was unreasonable for African leaders to continue with their policy of non-violent protest when the government met their demands with force. The decision to form MK, however, was not made by the ANC alone, but by a small leadership group comprised of Mandela, Sisulu and others representing the ANC, members of the Communist Party, South African Indian Congress (SAIC) and the South African Coloured Peoples Congress (SACPO). Mandela was appointed MK's first Commander-in-Chief. The decision to form MK was endorsed by a secret meeting of the Congress Alliance chaired by Chief Albert Luthuli, despite the fact that Chief Luthuli was staunchly against violent resistance.

On 11 January 1962, Mandela travelled under a pseudonym, David Motsamayi, to Bechuanaland (Botswana) and made a surprise appearance, via Dar es Salaam in Tanzania, at the Pan-African Freedom Movement Conference in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. This 'Bechuanaland Aerial Pipeline' had been used by other South African political refugees and freedom fighters and is examined in greater detail by Garth Benneyworth in his essay, 'Bechuanalands's Aerial Pipeline: Intelligence and Counter Intelligence Operations against the South African Liberation Movements, 1960-1965'.While in Dar es Salaam, he met with the Tanzanian President, Julius Neyere, who agreed to facilitate a meeting with the Ethiopian Emperor, Haile Selassie, in which they would discuss Ethiopia as an option for MK military training.

Once in Addis Ababa, Mandela would meet ambassadors and leaders of many African political parties. Mandela's address to the conference on 3 February, a few weeks after the first sabotage attacks by MK, explained and justified the turn to violent action. The full text of his address can be read here. While interacting with other African political leaders, Mandela was able to gain insight into how the African National Congress was viewed across the continent. Garth Conan Benneyworth writes, in his dissertation entitled Armed and Trained, that "[...] Mandela learnt that the ANC alliance with South Africa's Communist Party and Indian political parties unsynchronised them with mainstream African nationalism. Two perceptions prevailed - the PAC represented African interests while the ANC, excessively influenced by white communists was essentially their stooge. To worsen matters, some viewed Chief Luthuli's recent Nobel Prize as the West having bought the Chief. This theme - being out of step - was a matter that Mandela believed he had to address."After viewing a military parade in Ethiopia, Mandela travelled to Casablanca, Morocco where he received 'guerrilla' training by the National Liberation Front of Algeria (FLNA). He trained with various rifles, pistols, explosives and in hand-to-hand combat. Furthermore, Mandela's conversations with the leaders of various resistance groups from Angola, Mozambique, Algeria and Cape Verde provided insight into armed struggle against a colonial power. In particular, Mandela found the advice of the leader of the Algerian mission in Morocco, Dr Mustafa to be 'brilliant'. In Armed and Trained, Benneyworth writes that "Mustafa outlined that a key part of the general plan is military action, followed by the political objective and then psychological warfare. International opinion, Mustafa said, 'is sometimes worth more than a fleet of jet fighters.'"

Mandela then travelled to London where he met with leaders of British opposition parties. He returned to South Africa in July, once again via the British protectorate of Bechuanaland (modern day Botswana), and he travelled to Tongaat in Natal to meet with the banned ANC President Albert Luthuli, ostensibly to discuss the issue of the ANC's image in Africa. After visiting friends in Durban, he was driving back with his friend Cecil Williams to Johannesburg disguised as his chauffeur. On 5 August, they were stopped and arrested just outside the Natal midlands town of Howick. It is alleged that the police were informed of Mandela’s movements by an American Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) agent based in Durban. It is known, however, that Mandela's movements were followed by the British, American and South African intelligence services. Mandela was tried in Pretoria's Old Synagogue and in November 1962 sentenced to five years' imprisonment for incitement and illegally leaving the country. He was imprisoned at Pretoria Central Prison where he met his old friend and political opponent Robert Sobukwe, the leader of the breakaway PAC. Mandela spent seven months at Pretoria Central Prison before he was transferred to Robben Island.

In July police raided the underground safe house of the South African Communist Party at Lilliesleaf Farm, Rivonia Johannesburg, Transvaal (now Gauteng). Among those arrested were Walter Sisulu, Govan Mbeki, Raymond Mhlaba, Ahmed Kathrada, Dennis Goldberg and Lionel Bernstein. Police found Mandela's diary of his African tour, documents relating to the manufacture of explosives, and copies of a draft memorandum entitled 'Operation Mayibuye', which set out the stages and requirements for a 'guerrilla' war. The Rivonia Trial, as it came to be known, commenced in October 1963. Mandela was brought from Robben Island to stand trial with the rest of his comrades on charges of sabotage, conspiracy to overthrow the government by revolution, and assisting an armed invasion of South Africa by foreign troops. Mandela and his co-accused were convinced that they would be executed. Mandela, in a statement from the dock at the end of their trial, gave a powerful address in which he explained why he had turned from non-violent protest to armed struggle. ‘I am Prepared to Die’, as the statement came to be known, received worldwide publicity and enhanced Mandela’s status as a leader of the South African liberation struggle.

Imprisonment on Robben Island

On 12 June 1964 all the accused were sentenced to life imprisonment and held at Pretoria Central prison. That same night Mandela and his co-accused were flown by a military plane to Robben Island Prison just outside Cape Town, Western Cape. Upon arrival at the Robben Island airstrip, Mandela and the others were handcuffed, loaded into a vehicle and taken into an old building, known as B Section, which was still under construction, where he would be imprisoned. . He was issued with prison clothes, short pants, no socks and sandals - not shoes. The issuing of short pants and sandals was significant as it was calculated by the prison authorities to undercut their rights as men to wear long pants and shoes. This demonstrates that the apartheid logic of racial subjugation and segregation extended to the prison system as African prisoners received different food rations and clothes in contrast to their Indian and Coloured inmates. Mandela and his comrades were held in the Old Jail until 25 June.

Nelson Mandela and Walter Sisulu chat while working in the Robben Island Prison courtyard. Source: STE Publishers

Mandela was relocated to B section once its construction was complete. This section housed leaders and politically influential figures in single cells from across political formations, separate from other political prisoners and common law prisoners as the state feared that the political influence of these prisoners would spread. As a result, Mandela and his comrades were imprisoned together, along with leaders of other Southern Africa political organisations. For instance, he shared B Section with leading figures of the Pan Africanist Congress (PAC), African Resistance Movement (ARM) and the National Liberation Front (NLF). In addition, there was also a member of South West African People’s Organisation (SWAPO), Andimba Herman Toivo ya Toivo, demonstrating that political prisoners were brought to Robben Island Prison B section from as far afield as South West Africa (modern day Namibia). In the 1960s, there were about 30 prisoners in B Section. In January 1965, Mandela alongside other B Section prisoners were forced to work at the Lime Quarry where they dug lime which was used to pave roads. He was exposed to the glare of the lime particularly during summer resulting in eye damage despite his three year fight against prison authorities to obtain dark glasses for protection. In 1966, he took part in the hunger strike that was aimed at forcing prison officials to improve the food quality. Daily routine involved working for eight hours a day breaking slate boulders into gravel-sized stones. Prisoners were allowed one letter and one family visit every six months.

His wife, Winnie Madikizela Mandela, visited him in July 1966 after being granted permission to do so by the government on condition that she had a passbook. The visit was 30 minutes long and their conversations were monitored by prison guards. This was followed by another visit in June 1967. Then the following year, in 1968, Mandela was visited by his mother, who was accompanied by his sister Mabel, his eldest daughter Makie and youngest son Makgatho. After visiting him, his mother died a few weeks later and prison authorities refused to grant him permission to bury his mother. Tragedy struck the Mandela family again in 1969 when his eldest son, Thembi, died in road accident. Mandela sent a condolence letter to his ex-wife, Evelyn Mase, his only correspondence with her while he was in prison. Nevertheless, the death of his son affected Mandela deeply. He would write later in his autobiography, Long Walk to Freedom, "What can one say about such a tragedy? I do not have words to express the sorrow or the loss I felt. It left a hole in my heart that can never be filled."

There were also visits from government officials, members of Parliament and other political figures from outside South Africa, demonstrating Mandela’s influence on and role in the anti-apartheid struggle. In 1976, the Minister of Prisons Jimmy Kruger visited him and offered to release him on condition that he recognized the independence of the Transkei, and that he goes to live there. Mandela rejected this offer by Kruger outright. That same year Helen Suzman, a member of the Progressive Party, visited him in prison. Dennis Healey, a British MP from the Labour Party, visited Mandela on Robben Island demonstrating the extent to which Mandela’s celebrity status had grown internationally.

Nelson Mandela takes a break during work at Robben Island prison. Source: The Nelson Mandela Centre of Memory

In the 1970s, prisoners were allowed to keep a vegetable garden after years of petitioning the authorities. Mandela took a great interest in gardening. By 1975, Mandela had been reclassified as an “A” group prisoner allowing him three letters and two non contact visits every six months. Between 1975 and 1976, Mandela was writing his autobiography with help from Walter Sisulu and Ahmed Kathrada. Mac Maharaj was due for release in 1976, and it was felt that Mandela’s biography could be smuggled out of prison by Maharaj. Mandela spent four months secretly writing his autobiography by night, holding discussions with Sisulu and Kathrada throughout. His script was transcribed by Mac Maharaj and Laloo Chiba and hidden in Maharaj’s study books. Mandela’s original manuscripts were wrapped in plastic cocoa containers and buried in different sections of the garden. As planned, Maharaj smuggled copies of Mandela’s autobiography on his release. But in 1977, when prison authorities began building a wall to completely isolate B Section, they discovered the manuscript hidden in the garden. As a consequence, study privileges for Mandela, Kathrada and Sisulu were revoked for four years. The originally transcribed manuscript was never read by the public as the ANC did not want to publish the material while Mandela was still in jail. The original manuscript would, however, form the basis of his autobiography, Long Walk to Freedom, published in 1995.

On 31 March 1982 Mandela, Walter Sisulu, Raymond Mhlaba and Andrew Mlangeni were transferred from Robben Island to Pollsmoor Prison, while Ahmed Kathrada, Elias Motsoaledi and Govan Mbeki were left behind. They were also finally moved to Pollsmoor in April. That same year a campaign demanding the release of all political prisoners was launched in South Africa and abroad. The campaign was titled ‘Release Nelson Mandela’ and together with the campaign for economic and other sanctions against South Africa become the symbol of the international Anti-Apartheid Movement. This campaign became one of the most powerful international solidarity movements in history. With the apartheid government reeling under international pressure and mounting internal unrest, State President P.W. Botha was forced to issue a statement on 31 January 1985 that he was prepared to release Mandela and other Rivonia Trialists. This was on condition that he renounced violence and the armed struggle. Mandela issued his response through a letter read by his daughter, Zinzi Mandela, at a United Democratic Front (UDF) organised Rally in Soweto which rejected the offer. Despite this rejection, Botha repeated his willingness to release Mandela on 15 February under the same conditions stated in the previous statement, but Mandela stood his ground. From July 1986 onwards, a small group of the government and intelligence agents visited Mandela to persuade him to renounce the armed struggle. Mandela refused but did not close the door to dialogue with the government. He had contact with government representatives, first with Minister of Justice Kobie Coetzee and subsequently with Minister of Constitutional Development, Gerrit Viljoen.

In 1988, the ANC and the Mass Democratic Movement (MDM) inside South Africa planned worldwide celebrations to mark Mandela's 70th birthday and prepared for mass celebrations inside the country. The government banned all gatherings and arrested some activists and leaders of the birthday celebrations. A 12-hour music concert in London, broadcast to over 50 countries, drew enormous attention and many foreign countries pressured the South African government to release Mandela. On 12 August 1988, Mandela was taken to Tygerberg Hospital in Cape Town for treatment for fluid on the lungs. He stayed in hospital for six weeks. It was subsequently revealed that he was suffering from tuberculosis. On 31 August, he was transferred to the Constantiaberg Medi-Clinic where he was treated until 7 December. From here, Mandela was moved to a house in the grounds of the Victor Verster Prison, near Paarl, Western Cape. On 4 July 1989, Mandela held a short meeting with State President P.W. Botha at Tuynhuys in the Parliamentary precinct. The meeting was historic as this was the first time the two men had met face to face. The meeting was courteous and polite, yet Botha rejected Mandela’s request for the unconditional release of all political prisoners. In spite of this, the two maintained a cordial relationship after the end of apartheid with Mandela visiting Botha’s Wilderness home on a few occasions after his release from prison. One can view this relationship as an example of Mandela’s commitment to reconciliation post-apartheid. Botha resigned as state president in August 1989 and was succeeded by F.W. De Klerk.

In December 1989, Mandela met the new state president, FW de Klerk. Unknown to the government, Mandela had kept Oliver Tambo, the President of the ANC in exile, informed of his discussions with the government through Mac Maharaj, a former Robben Island prisoner and a confidant of Mandela. Maharaj, who had fled into exile, had secretly entered South Africa and established a highly sophisticated underground network known as ‘Operation Vula’. In addition to meeting government representatives, Mandela was allowed to meet with senior members of the United Democratic Front (UDF), the Congress of South African Trade Unions (COSATU) and other political groups. At this point, the government realised that apartheid was nearing its end, and opted for formal negotiations with the ANC through Mandela.

From prisoner to President

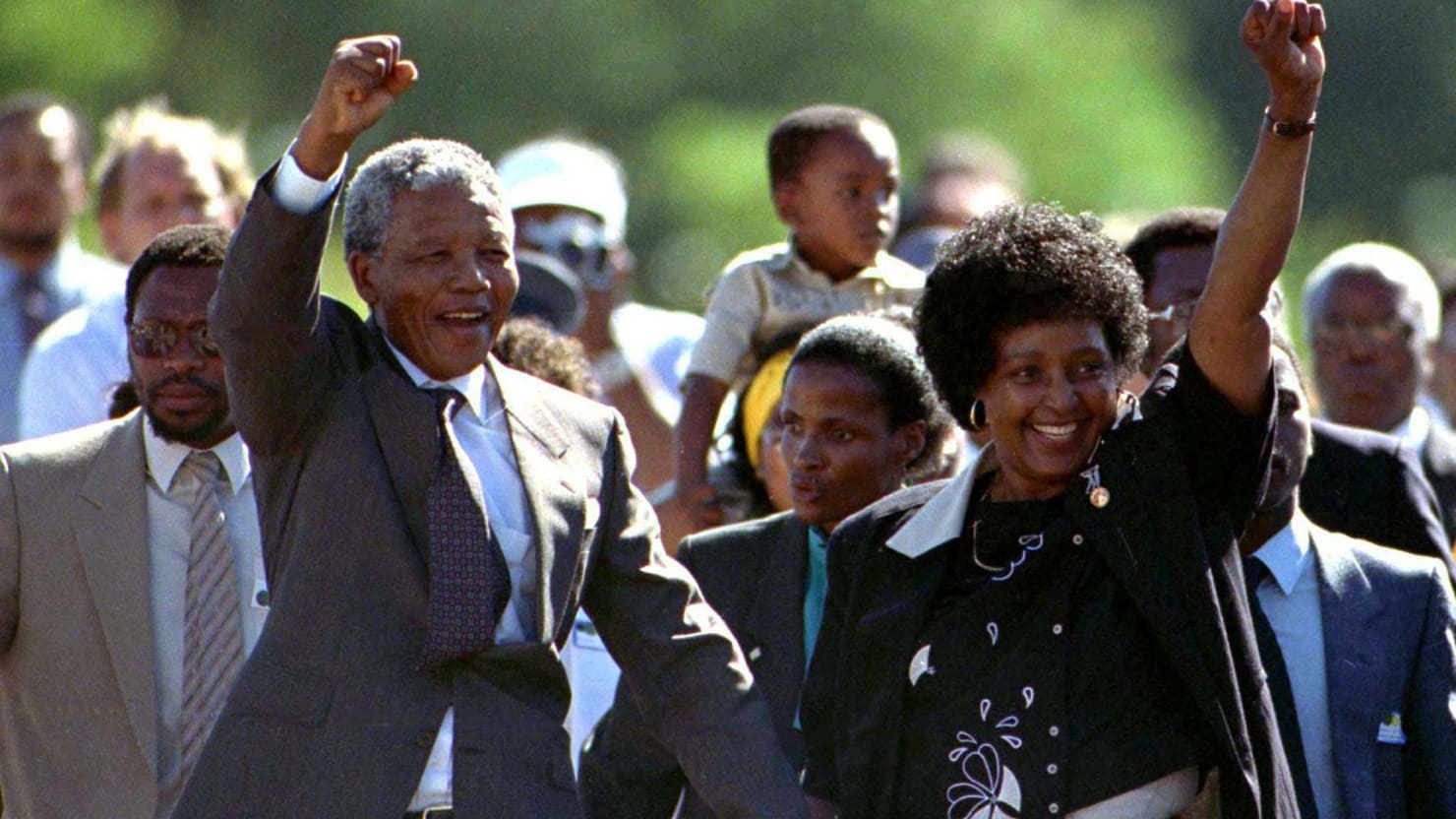

Nelson Mandela and his wife Winnie, after his release from Victor Verster Prison, February 1990. Source: Getty Images

On 2 February 1990, State President FW de Klerk, in his opening speech in parliament, announced the unbanning of the ANC and all other proscribed political parties, and the release of Mandela and all other political prisoners. On Sunday 11 February, after 27 years in prison, Mandela was released from Victor Verster Prison. That same day he addressed a mass rally in the centre of Cape Town, his first public appearance in nearly three decades, beginning his speech with, “I greet you all in the name of peace, democracy and freedom for all”. The subsequent welcome rallies held in Soweto and Durban drew thousands of people.

The following month Mandela travelled to Lusaka to meet the ANC's Executive Committee. The ANC had announced their intention to move its headquarters from Lusaka to Johannesburg as soon as possible. While meeting with the Executive Committee, Mandela was elected Deputy President of the ANC. He then travelled to Sweden to meet his comrade and friend, the incumbent ANC president Oliver Tambo, but had to cut short the rest of his proposed trip abroad as a result of increased unrest in South Africa. The government of the ‘independent homeland’ of Ciskei had been overthrown by a military coup, led by Brigadier Oupa Gqozo, on 4 March. Adding to the chaos of this time, the apartheid government gave emergency powers to the President, allowing de Klerk to govern in a state of emergency. Later in March, police opened fire on anti-apartheid protesters in Sebokeng, killing 14 people and wounding more than 380.

In May 1990, Mandela headed an ANC delegation in talks with the South African government representatives at Groote Schuur in Cape Town. At the end of the meeting a document known as the Groote Schuur Minute was signed. This signified a commitment from both the ANC and the government to end the political violence which had gripped the country. Furthermore, a working party was formed, including ANC cadres, to advise on the release of political prisoners. In June, he began a six week tour of Europe, the United Kingdom, North America and Africa. His reception by heads of state and hundreds of thousands of admirers confirmed his stature as an internationally respected leader. In July that year he attended the Organisation of African Unity (OAU) summit held in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia but had to leave for Kenya when he contracted pneumonia. Talks resumed with the South African government in August and in the same month Mandela visited Norway. This was followed by visits to Zambia, India and Australia.

In February 1991, Mandela met with Chief Mangosuthu Buthelezi, president of the Inkatha Freedom Party (IFP), in an attempt to end the political violence sweeping Natal and the Transvaal as the IFP and ANC fought for political control of the provinces. Further fanning the flames of this conflict was alleged government interference, the so-called ‘third force’. However, despite their pledges to work towards peace, the violence continued. Mandela then issued an ultimatum to the government, setting a deadline by which it had to fire the Minister of Defence and Minister of Law and Order and end the ongoing violence. He indicated that the ANC would quit the negotiation process if these demands were not met. The government failed to meet these demands.

Mandela addressing the press after a meeting between the government and the ANC at Groote Schuur. Image source

Mandela attended a meeting between the ANC and the PAC in Harare in April 1991, where the movement resolved to work together to oppose apartheid. The two parties had previously been split on ideological issues regarding the role of non-Africans in the struggle for freedom. The meeting also agreed to convene a conference of anti-apartheid organisations in support of the demand for a national constituent assembly. In June 1991, Mandela attended the Organisation of African Unity (OAU) summit in Abuja, Nigeria, following which he travelled to the United Kingdom and Belgium. A month later, at the ANC conference in Durban, he was elected ANC president, succeeding the ailing Oliver Tambo. In August, Mandela travelled to countries in South America. These visits were to drum up investor support for the future post-apartheid South Africa as well as trading on Mandela’s international celebrity.

He signed the National Peace Accord on behalf of the ANC in September, 1991. This agreement between a number of political organisations, including the ANC, Inkatha Freedom Party and the National Party, established structures and procedures to attempt to end political violence which had become widespread. In October 1991, a meeting of the Patriotic Front was held in Durban in an attempt to bring together all the anti-apartheid groupings in the country. All attended with the exception of the Azanian People's Organisation (AZAPO). Policy regarding future negotiations was formulated and the ANC and the PAC began preparatory meetings for the Convention for a Democratic South Africa (Codesa). However, the PAC could not see its way clear to participate in the convention due to its belief that the convention should be held outside the country under the stewardship of a neutral party. In November that year, Mandela travelled to West Africa and the following month, met United States President, George Bush Snr.

The first meeting of Codesa, set up to negotiate procedures for constitutional change, was held in December 1991. At the end of the plenary session, after De Klerk had raised the question of disbanding Umkhonto we Sizwe, Mandela delivered a scathing personal attack on him. Mandela argued that even the head of an illegitimate and discredited minority regime should have certain moral standards. During 1992, Mandela continued his programme of extensive international travel, visiting Tunisia, Libya and Morocco. He and De Klerk jointly accepted Unesco’s Félix Houphouët-Boigny Peace Prize in Paris on 3 February. At the same time the two men attended the World Economic Forum (WEF) in Davos, Switzerland. On 13 April 1992, Mandela called a press conference at which he announced that he and his wife, Winnie, had agreed to separate as a result of differences which had arisen between them in recent months. Later in April Mandela, De Klerk and the IFP’s Chief Buthelezi addressed a gathering of more than a million members of the Zion Christian Church (ZCC) at Moria, near Pietersburg (now Polokwane, Limpopo Province), and committed themselves to end the ongoing violence and move speedily towards a political settlement.

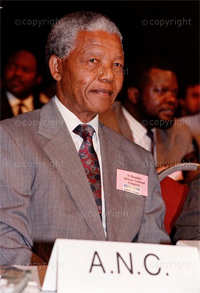

Nelson Mandela at CODESA, December 1991 Photograph: Graeme Williams. Permission: Africamediaonline

In May 1992, the second plenary meeting of Codesa was held, but the working group dealing with constitutional arrangements reached a deadlock when the ANC and the government could not reach agreement on certain constitutional principles. Codesa's management committee was asked to find a way out of the logjam but by 16 June (by then known as Soweto Day) no progress had been made and the ANC called for a mass action campaign to put pressure on the South African government. While visiting the Scandinavian countries and Czechoslovakia in May, Mandela suggested that FW de Klerk was personally responsible for the political violence in South Africa. He likened the violence in South Africa to the killing of Jews in Nazi Germany. Mandela also criticised what he felt was the stranglehold imposed on the South African press, which represented White-owned conglomerates; however, he expressed support for a critical, independent and investigative press.

Following the Boipatong massacre of June 1992, Mandela announced the suspension of negotiations until the ANC’s demands were met, including that the government take steps to end political violence, form a transitional government and move towards the election of a constituent assembly. At the end of June, Mandela addressed a Heads of States Summit of the Organisation of African Unity (OAU) in Dakar, Senegal. The OAU agreed to raise the issue of South Africa's continuing political violence at the United Nations (UN). In July, Mandela and representatives of other South African parties addressed the UN Security Council. Mandela asked the UN to provide continuous monitoring of the violence and submitted documents, which he claimed, proved the 'criminal intent' of the government, both in the instigation of violence and in failing to curb it. He maintained that the government was conducting a 'cold-hearted strategy of state terror to impose its will on negotiations'. On his return to South Africa, Mandela called for disciplined and peaceful protest and involved himself in the ANC's mass action campaign. Following violent incidents between ANC supporters in the Transvaal, Mandela admitted that the organisation had disciplinary problems with some of its followers, particularly in township Self-Defence Units and promised to take action against those who abused their positions of power and authority.

Mandela indicated in September 1992 that he was prepared to meet De Klerk on condition that he agreed to fence off township hostels, ban the public display of dangerous weapons and release political prisoners. They met at the end of the month and these bi-lateral talks resulted in the signing of a Record of Understanding between the two leaders, thereby enabling negotiations to resume.

During 1992 and 1993 Mandela repeatedly called for peace. Following the assassination of the South African Communist Party (SACP) leader, Chris Hani, in April 1993, he again called for restraint, discipline and peace. At a rally in Soweto's Jabulani Stadium he was booed by a militant crowd when he tried to convey a message of peace in the wake of the killing. Mandela caused a political row in May when he suggested that South Africa's voting age should be lowered to enable 14 year old children to vote. However, he was persuaded to accept that only people aged 18 and above could vote in the April 1994 elections. In September 1993, after the election date had been set for 27-29 April 1994, Mandela used a visit to the United States of America to urge world business leaders to lift economic sanctions and invest in South Africa. During the latter half of 1993 and early 1994 he campaigned on behalf of the ANC for the 1994 election and addressed a large number of rallies and people's forums. At the same time, he continued his efforts to draw the Freedom Alliance partners (White right wing groups, IFP, Bophuthatswana and Ciskei Bantustan governments) into the election process. However, he ruled out the possibility of delaying the election date to accommodate them.

In March 1994, following a civil uprising in the homeland of Bophuthatswana, which led to the downfall of the Mangope government, Mandela guaranteed striking civil servants their jobs, but harshly criticised the looting that had occurred during the unrest. In April, last minute talks were held in the Kruger Park between Mandela, De Klerk, Buthelezi and Zulu King Goodwill Zwelithini to try to break the deadlock on IFP participation in the elections. The meeting was unsuccessful and was followed by an attempt at international mediation. This, too, failed, but a final effort by Kenyan academic, Washington Okumu, brought the IFP back into the election process. Mandela and De Klerk then signed an agreement stating that the institution, status and role of the King of the Zulus, as well as the Kingdom of KwaZulu, be recognised and protected. Mandela contested the April 1994 election as the head of the ANC. He cast his vote in Inanda, Durban, on the first day of voting on 27 April 1994. Early in May, the Independent Electoral Commission (IEC) announced that the ANC had won 62% of the national vote. Mandela indicated his relief that the ANC did not achieve a two-thirds majority, as this would allay fears that it would unilaterally re-write the constitution. He restated his commitment to a government of national unity wherein each party shared in the exercise of power.

Nelson Mandela casts his vote for the first time in April 1994. Photographer: Paul Weinberg, Permission: Africamediaonline

On 9 May, Mandela was elected unopposed as president of South Africa in the first session of the Constituent Assembly. His presidential inauguration took place the next day at the Union Buildings in Pretoria and was attended by the largest gathering of international leaders in South African history, as well as about 100 000 jubilant supporters on the lawns. The ceremony was televised and broadcast internationally. In his inaugural speech Mandela called for a 'time of healing' and stated that his government would fight against discrimination of any kind. He pledged to enter into a covenant to build a society in which all South Africans, Black and White, could walk tall without fear, assured of their rights to human dignity, 'a rainbow nation at peace with itself and the world'. In his State of the Nation speech in parliament on 24 May 1994, Mandela announced that R2.5 billion would be allocated in the 1994/95 budget for the government's Reconstruction and Development Programme (RDP). This policy focused on basic needs such as jobs, land, housing, water, electricity, telecommunications and transport, among others. Furthermore, this policy emphasised that the people should be part of the decision making process. His pragmatic economic policy was welcomed by business in general.

Mandela continued to draw the White right wing into the negotiation process and in May, 1994 held a breakthrough meeting with the leader of the Conservative Party (CP), Ferdie Hartzenberg. Negotiations also involved a possible meeting with Eugene Terre Blanche, leader of the right wing Afrikaner Weerstandsbeweging (AWB), but it did not transpire. In June, Mandela attended the OAU summit in Tunis and was appointed second vice-president of the organisation. The following month he held talks with his Angolan, Mozambican and Zairean counterparts in an attempt to further peace-making efforts in Angola. UNITA leader Jonas Savimbi welcomed his participation in the Angolan peace process. Mandela underwent eye surgery for a cataract in July. The operation was complicated by the fact that his tear glands had been damaged by the alkalinity of the stone at Robben Island where he had done hard labour breaking rocks.

In September 1994, Mandela made a crucial speech at the annual conference of the Congress of South African Trade Unions (Cosatu) where he called on the labour movement to transform itself from a liberation movement to one that would assist in the building of a new South Africa. In this speech, he urges workers and COSATU to assist in making the ANC's RDP programme work and to challenge the notion that strikes are ‘inimical to the task of reconstruction and development’. The government of national unity nearly collapsed in January 1995 over an alleged secret attempt by two former cabinet ministers and 3 500 police to obtain indemnity on the eve of the April 1994 elections. At a cabinet meeting on 18 January, Mandela attacked Deputy President De Klerk, stating that he did not believe De Klerk was unaware of the indemnity applications. He went on to question De Klerk's commitment to reconciliation. At a press conference on 20 January, De Klerk maintained that this attack on his integrity and good faith could seriously jeopardise the future of the government of national unity.

In April 1995, Mandela removed his estranged wife, Winnie Madikizela-Mandela, as Deputy Minister of Arts, Culture, Science and Technology, following a series of controversial issues in which she was involved. She challenged her dismissal in the Supreme Court, claiming that it was unconstitutional. She obtained an affidavit from IFP leader Mangosuthu Buthelezi to the effect that he had not, as a leader of a party in the government of national unity, been consulted about her dismissal. This was a constitutional requirement. Winnie Mandela was then briefly reinstated before being dismissed again, Mandela having consulted with all party leaders involved in the government. Mandela and Madikizela-Mandela would divorce in 1996 due to political differences and the tension which she was causing within the ANC. An example of this was Madikizela-Mandela’s repeated contradiction and repudiation of the ANC’s policy of reconciliation and her refusal to co-operate with the rest of the ANC leadership.

In May 1995, following a dispute between the IFP and the ANC regarding international mediation for the new constitution, Buthelezi called on Zulus to 'rise and resist' any imposed constitutional dispensation. Mandela accused Buthelezi of encouraging violence and attempting to foment an uprising against central government. In this context, Mandela threatened to cut off central government funding to KwaZulu-Natal, indicating that he would not allow public funds to be used to finance an attempt to overthrow the constitution by violent means. Although a subsequent meeting between the two leaders seemed cordial in tone, the matter of mediation remained an unresolved point of conflict and the ANC’s relationship with the IFP remained strained.

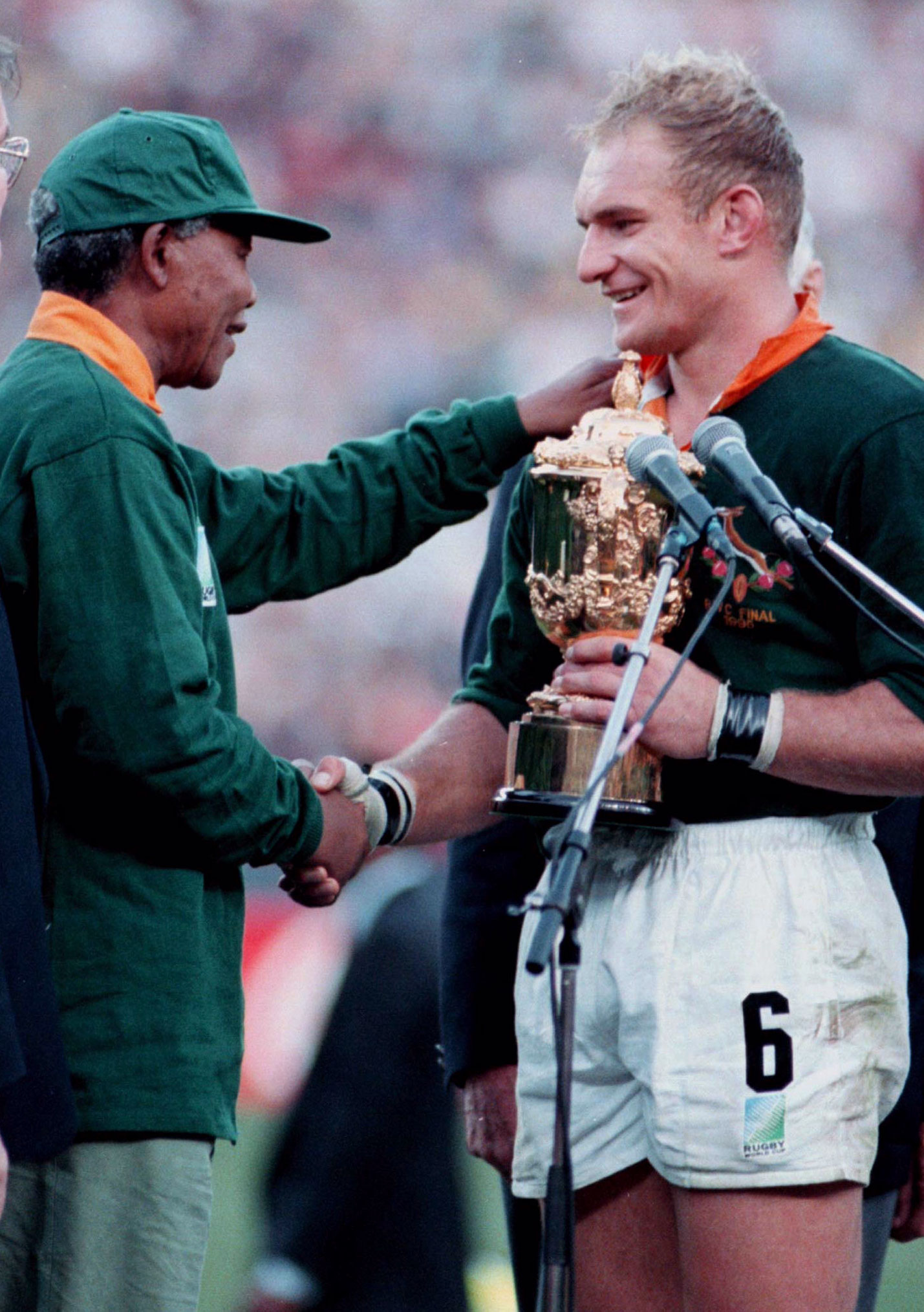

President Nelson Mandela presents the William Webb Ellis trophy to Springbok captain, Francois Pienaar, at the 1995 Rugby World Cup hosted in South Africa Image source

In 1995 the Rugby World Cup was held in South Africa. South Africa had recently been allowed to compete in international events after the dissolution of apartheid. Mandela saw this tournament as an opportunity to unite the country and diffuse the racial tensions which had built up before the 1994 elections. The South African national rugby team (nicknamed the Springboks) won the tournament, and in an iconic moment, Mandela presented the trophy to the captain of the team, Francois Pienaar, while wearing a Springbok jersey. This action highlights Mandela’s dedication to reconciliation as the Springbok rugby team long been associated with the apartheid government due to rugby being by far the most popular sport amongst white South Africans.

On his eightieth birthday on 18 July 1998, he married his third wife, Graca Machel. Machel, at the time, was the widow of Mozambican president, Samora Machel. Graca Machel has served as Minister of Education and Culture in Mozambique (1975 - 1989) as well as on various humanitarian committees devoted to women’s and children’s rights.

Retirement from political life

Mandela retired from active political life in June 1999 after his first term of office as president. He was succeeded by Thabo Mbeki, who had been elected as ANC president in 1997. Mandela continued to play an active role in mediating conflicts around the world. For instance, in 2000 he was appointed mediator in the war-torn, Burundi, a mission he accomplished with aplomb.

President Mandela retired from active political life in June 1999.

In 2003, he was diagnosed with prostate cancer. He devoted a large amount of his time to raising funds for the Nelson Mandela Children's Fund. In November 2003, a concert was held at Green Point Stadium to raise funds for the Nelson Mandela Foundation, the Nelson Mandela Children’s Fund and global AIDS organisations. International musicians such as Beyonce, Queen and The Who responded to Mandela's call, as well as local artists such as Johnny Clegg, Danny K and the Soweto Gospel Choir. The concert was called Nelson Mandela's 46664 Global AIDS initiative as 466/64 was Mandela’s prison number during his 27 years of incarceration. This concert would be the first of six international concerts of the same name that took place between 2003 and 2008.

Evelyn Mase passed away on 4 April, 2004 and Mandela cut short his overseas trip to attend her funeral. On 10 May 2004, Mandela addressed a joint-sitting of parliament in celebrating a decade of democracy in which he acknowledged the extraordinary position he was in, being allowed to address Parliament despite not being an MP or sitting leader. Furthermore, he stated that while incredible steps had been taken in the 10 years of democracy, he urged governmental action on issues including poverty, unemployment, preventable disease and ill health, with specific mention of HIV/Aids. Throughout the months of April and May that same year, Mandela lobbied intensely in support of South Africa’s bid to host the 2010 World Soccer Cup. According to him, it would be a fitting present for the 10 years of democracy. On 15 May 2004, he was in Zurich, Switzerland when South Africa was awarded the right to host the 2010 soccer showpiece. Mandela cried openly at the achievement. He said he felt like a 15-year-old boy and the memory would live with him forever.

46664 is a global HIV/AIDS awareness and prevention campaign.

On 1 June 2004, Mandela announced that he was bowing out of public life to lead a quieter life, issuing the now famous statement: ‘Don't call me, I'll call You’, to those who would require his presence at their functions. Though retired from public life, Mandela carried the Olympic torch on Robben Island on 14 June 2004 on its first journey on African soil since the inception of the Olympic Games. In 2005, in an attempt to destigmatise HIV and AIDS, he came out openly to announce that his son Makgatho, from his first wife Evelyn Mase, had died of AIDS. Mandela was the recipient of numerous awards and honours both within South Africa and abroad. In line with his desire to recede from the political limelight, the unending invitations to receive more awards and honours prompted him to publicly urge that other leaders in the struggle to liberate and democratise South Africa should be recognised and honoured as he had been.

His 88th birthday celebrations on 18 July, 2006 kicked off with a new round of honours, including a photo exhibit and the release of a book called The Meaning of Mandela during the week before his birthday. The event was meant to be part of a series of three, which the Nelson Mandela Foundation would be conducting to celebrate Mandela's birthday, according to Jakes Gerwel, chairman of the foundation's board. The photo exhibition by South African veterans Alf Khumalo and Jurgen Schadeberg capture Mandela's years as a young lawyer and the emergence of Black resistance before he was jailed for 27 years in 1964 and includes photographs of his family.

Events to celebrate the birthday of the ageing statesman that year also included a ceremony to present him and fellow graduates of Fort Hare University with honorary rings, as well as the Nelson Mandela Annual Lecture, to be delivered by South African President Thabo Mbeki. However, he also spent some quiet time with his family. Although he retired from active politics and cut down on functions, Mandela still continued to do charitable work. He campaigned for health and educational issues through the Nelson Mandela Foundation and the Nelson Mandela Children’s Fund. As part of his 89th birthday in 2007, Mandela established The Elders, a group of 12 eminent leaders chaired by Archbishop Desmond Tutu, who aim to use their wisdom to tackle global problems. Archbishop Tutu and Graca Machel were integral with regards to the founding of this organisation and are still associated with The Elders as of 2018.

On 30 April 2008 the US Secretary of State Condoleezza Rice called the flagging of Mandela on the US terrorist watch lists "embarrassing”, and US lawmakers’ erased references to Mandela as a terrorist from national databases on 26 June. To celebrate his 90th birthday, the Soweto Heritage Trust began restoration work on Mandela House, in Soweto. The United Nations General Assembly announced on 10 November 2009 that Mandela's birthday, 18 July, would henceforth be known as “Mandela Day” marking his contribution to freedom and human rights. This is the first time that the United Nations (UN) has designated a day dedicated to a person. The UN also asked the people of the world to set aside 67 minutes of their day to undertake a task that would contribute to bringing joy or relief to the millions of disadvantaged and vulnerable people of the world.

In June 2010, tragedy struck the Mandela family when Zenani, Mandela’s great-granddaughter, was killed in a car accident. He was forced to cancel plans to attend the opening of the 2010 FIFA World Cup at Soccer City, Johannesburg. She was buried on 17 June. However, Mandela was able to briefly attend the closing ceremony of the Soccer World Cup at Soccer City, Johannesburg.

President Mandela and his wife Grace Machel wave to people during the closing ceremony of the 2010 World Cup at Soccer City stadium in Johannesburg, Photographer: Michael Kooren, Image Source

At the beginning of January 2011, Mandela was checked into Milpark Hospital with acute respiratory difficulties but returned home on 28 January. Mandela soon moved back to his home in Qunu, in the Eastern Cape. On 27 March of the same year, Google and The Nelson Mandela Centre of Memory’s launched the Nelson Mandela Multimedia Archive. The archive digitises photographs, recordings and documents related to Mandela and make them available online. Throughout 2012 and 2013, rumours abounded about Mandela's failing health until the nation's worst fears were confirmed on 5 December, 2013. Mandela had passed away in Houghton Estate in Johannesburg. His memorial service was held 15 December in the FNB Stadium, Johannesburg and was attended by 91 sitting heads of state and a number of other dignitaries. Mandela is survived by a daughter from his first marriage to Evelyn Ntoko Mase. Mandela is also survived by two daughters with his second wife, Winnie Madikizela-Mandela. From these children, he is survived by 18 grandchildren.